Take the Caldwell challenge

Celebrate the life of Patrick Moore with 10 deep-sky objects from his own astronomical catalogue

The early spring nights of March are ideal for discovery, something Patrick Moore, our late Editor Emeritus, was keen to encourage. To celebrate what would have been Patrick’s 100th birthday, we’ve put together a special challenge based on his very own Caldwell Catalogue.

We’re inviting you to take a tour of 10 of our favourite objects from his list, all of which are visible this month. Your task is to find them all in a single observing session. Some of the targets are quite popular, and you’ll have seen them in our monthly deep-sky and binocular tours, while others are a little less well-known. Hopefully you’ll be discovering some of these for the first time.

The minimum size telescope for this challenge is a 4-inch refractor: all of the objects are within reach of this size instrument under dark skies. Larger apertures will certainly help, of course, revealing hidden details that may otherwise elude you.

We suggest that you attempt the challenge near the third week of the month to avoid interference from the Moon’s light. A couple of days either side of 21 March, starting at about 20:00 UT and finishing at about 22:30 UT, would be a good goal if the clouds play fair.

As it is spring, don’t be caught out by a cold snap and be sure to wear suitable warm clothing and have some hot drinks on hand. Why not involve some friends and their telescopes in the challenge and make this a social occasion too?

The making of Moore’s marathon

Why did Patrick produce his own celestial catalogue, and what targets does it contain?

The Caldwell Catalogue came about because Patrick felt that the Messier Catalogue – a list of 110 objects originally created to tell comet hunters what to avoid – was somewhat incomplete. So he drew up a list of his favourite objects, all absent from Charles Messier’s magnum opus. With the ‘M’ of Moore already taken, Patrick opted to use the ‘C’ of Caldwell for the objects in his list (his full surname being Caldwell-Moore). Patrick’s catalogue contains 109 objects that, unlike Messier’s, are spread across both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. It includes 28 open clusters, 18 globulars, 35 galaxies, 13 planetary nebulae, 12 bright nebulae, one dark nebula and two supernova remnants, arranged in order of declination.

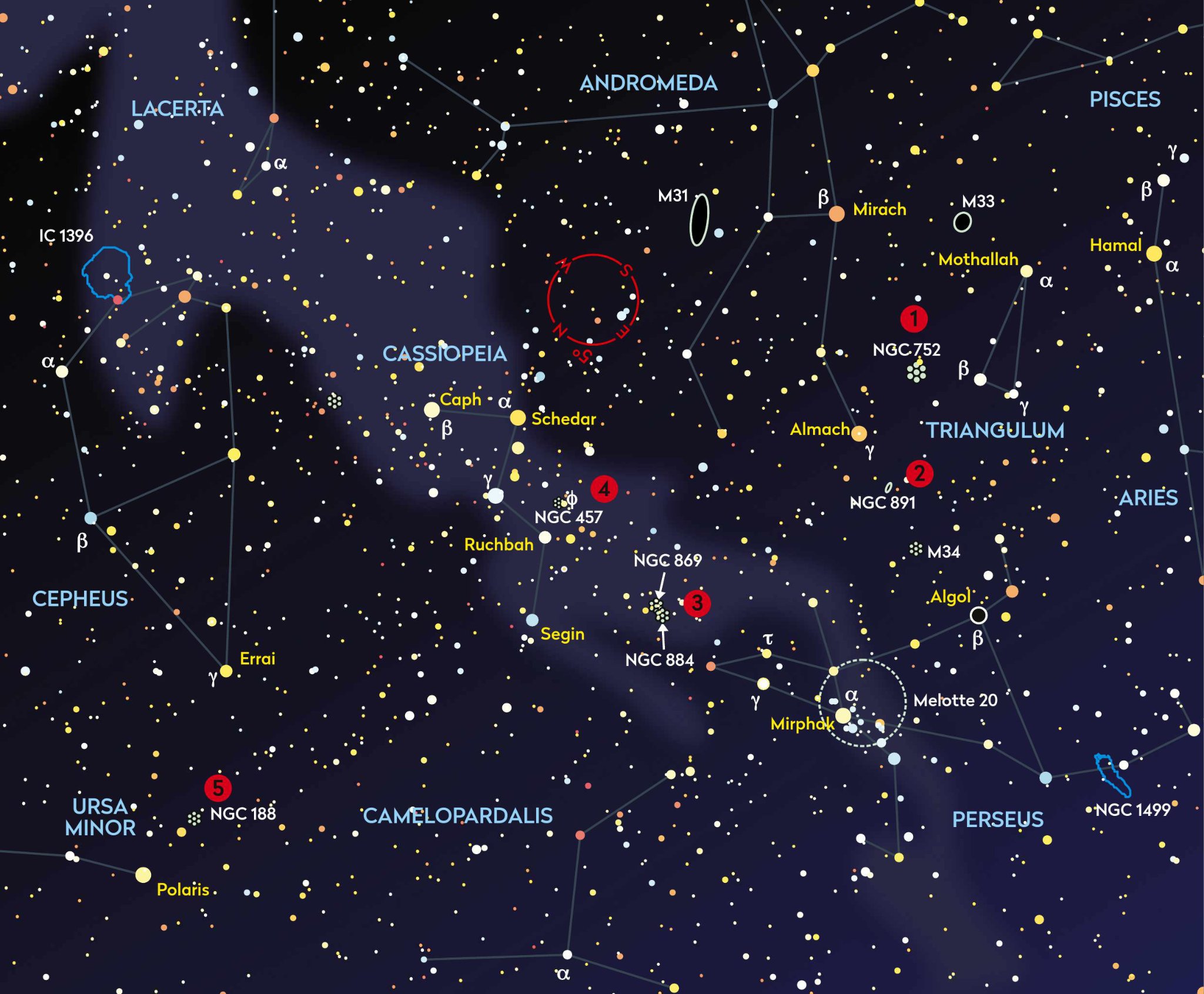

1. NGC 752

Also designated: C28

RA 1h 56m 53s, dec. 37° 47’ 38”

We start our challenge with a fine binocular object originally discovered by Caroline Herschel in 1783. Open cluster C28, also known as NGC 752, lies about one-third of the way between mag. +2.3 Almach (Gamma (γ) Andromedae) and the apex star in the constellation of Triangulum, mag. +3.4 Mothallah (Alpha (α) Trianguli). It can be easily found by sweeping between the two stars and, at almost two billion years old, this is one of the oldest star clusters known. Binoculars will show in the region of 30 widely scattered stars, although a richfield telescope at low magnification is the best way to really enjoy this lovely object, revealing in excess of 60 individual member stars, more than a dozen of which are brighter than mag. +10.0.

2. NGC 891

Also designated: C23

RA 2h 22m 36s, dec. 42° 21’ 00”

Moving nearly 7° northeast now, your second object lies one-third of the way along a line joining the stars Almach and mag. +2.1 Algol (Beta (β) Persei). We’re looking for mag. +9.9 edge-on galaxy NGC 891, and although it is visible in a 4-inch telescope, its low surface brightness means you may need to use averted vision. It is worth lingering here a little, as more and more detail will be revealed as your eye becomes accustomed to the view. If you can increase your aperture and up the magnification to around 120x, with careful scrutiny you should discern a slender dark dust lane bisecting the galaxy. This object was originally discovered by William Herschel in 1784 and it is believed to be over 30 million lightyears away from us.

3. Double Cluster

Also designated: C14, NGC 869 & NGC 884

RA 2h 19m 00s, dec. 57° 9’ 00”

Continuing our journey into Perseus, your next target is a real treat: two objects for the price of one! NGC 869 and NGC 884 are popularly known as the Double Cluster today; in antiquity it was the Sword Handle, referencing the jewel-encrusted sword given to Perseus by Athena and Hermes to help him behead the Gorgon Medusa (the latter is represented by the star Algol). The individual clusters are a fine sight through binoculars and can be seen with the naked eye from a dark location. A binocular sweep between mag. +3.9 Tau (τ) Persei and mag. +2.7 Ruchbah (Delta (δ) Cassiopeiae) will easily find them. NGC 884, the more easterly of the two, contains numerous white-blue stars, whereas NGC 869 is dimmer and more compact.

4. The Owl Cluster

Also designated: C13, NGC 457

RA 1h 19m 6s, dec. 58° 20’ 00”

We leave Perseus and continue into Cassiopeia, a constellation named after a queen who vainly boasted of her unrivalled beauty. There is real beauty here, though, with the aptly named Owl Cluster – although it is also sometimes referred to as the ET Cluster because its shape has been said to resemble the alien from the film of the same name. The brightest star visible in the cluster is one of the Owl’s eyes, mag. +5.0 Phi (φ) Cassiopeiae. It lies 2° southwest of Ruchbah, so is quite easy to find. In truth, bright red Phi Cassiopeiae is not actually a member of the cluster at all, but a foreground star. All the same, it certainly adds to the view through binoculars or a small scope.

5. NGC 188

Also designated: C1

RA 0h 47m 11s, dec. 85° 14’ 38”

Once you tick off this next object you’ll be half-way through the challenge. Located just 4° to the south of the Pole Star, Polaris, open cluster NGC 188 is often ignored by observers with equatorial mounts as locating objects this close to the pole can be a bit fiddly. But what’s an observing challenge without a bit of challenge? Unusually for an open cluster, this one comprises many older stars, more yellow than the hot, white, young stars that you might have expected. With a magnitude of +8.1, it’s not a naked-eye object, but a 4-inch telescope at 30x magnification will reveal it as a stretched scattering of stars set against a brighter circular core.

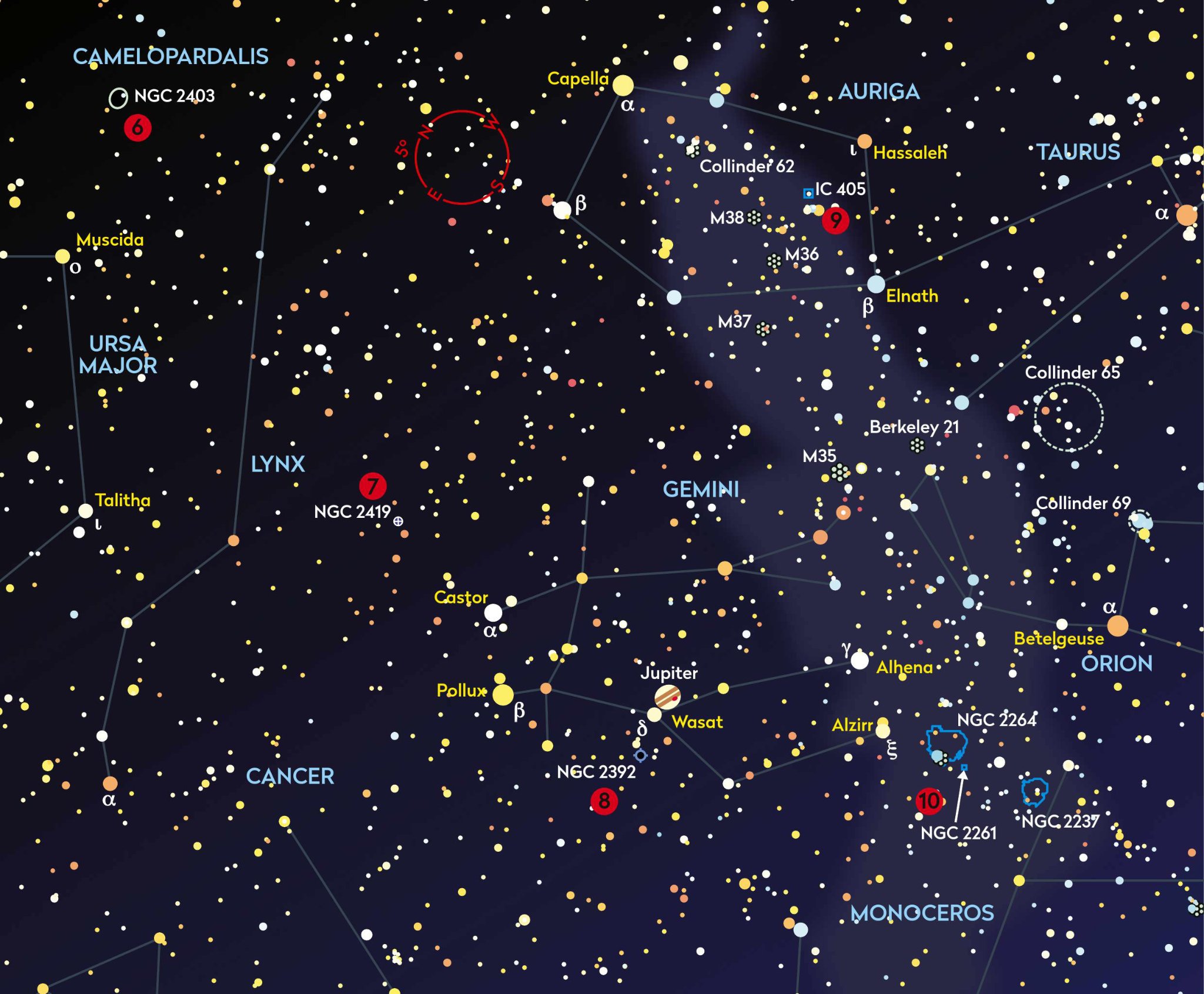

6. NGC 2403

Also designated: C7

RA 7h 36m 54s, dec. 65° 36’ 0”

We are half-way through, so now is a good time to take a break and warm up with a hot drink as you prepare for the second stint. Our first object in the final run is spiral galaxy NGC 2403 in Camelopardalis. It has an appearance very similar to that of the Triangulum Galaxy, with numerous HII star-forming regions within its two layers of spiral arms. Shining at mag. +8.9, this is one of the brightest galaxies in the sky – but again, like the Triangulum Galaxy it is large and that brightness is spread out. NGC 2403 is somewhat isolated in sparsely populated Camelopardalis. You can find it just under 8° west of mag. +3.3 Muscida (Omicron (ο) Ursae Majoris). A 4-inch telescope will show an elongated hazy patch, but you will need a 12-inch telescope to view the spiral arms.

7. The Intergalactic Wanderer

Also designated: C25, NGC 2419

RA 7h 38m 6s, dec. 38° 53’ 0”

A quick hop southwards into Lynx will take us to a distant globular cluster known as the Intergalactic Wanderer, as it was originally believed to be located outside the gravitational influence of the Milky Way (something we now know to be untrue). Discovered by William Herschel in December 1788, this cluster is one the remotest globulars ever found, at a distance of around 275,000 lightyears. Look for it 7° to the north of mag. +1.6 Castor (Alpha (α) Geminorum). It’s a difficult object in a 4-inch telescope, but a 10-inch or larger will reveal its condensed core and patchy halo.

8. NGC 2392

Also designated: C39

RA 7h 29m 12s, dec. 20° 55’ 0”

We continue our journey south into Gemini, sweeping past Castor and onwards to a point 2.4° southeast of mag. +3.5 Wasat (Delta (δ) Geminorum) to find a fascinating planetary nebula, NGC 2392. Although visible through a 4-inch telescope, with a diameter of only 48 arcseconds you’ll need at least a 6-inch telescope to show the true shape of the nebula. A 10-inch or larger instrument will reveal a host of other delicate details, including two distinct shells – abright inner mottled region with an outer faint halo, separated by a dark ring. The nebula’s very distinctive appearance wasn’t lost on William Herschel, who described it as “a very remarkable phenomenon” when he discovered it in 1787.

9. The Flaming Star Nebula

Also designated: C31, IC 405

RA 5h 16m 12s, dec. 34° 16’ 0”

Although our next object is an astrophotographer’s dream, it is more challenging for observers. The Flaming Star Nebula lies 4.2° east-northeast of mag. +2.7 Hassaleh (Iota (ι) Aurigae) and is a delightful mix of both reflection and emission nebulosity. The star responsible for generating all the energy is HD 34078, which can be clearly seen at the heart of the nebula. However, this star is here by chance: it’s just passing through on its long journey away from a cataclysmic interaction with the Trapezium stars in the Orion Nebula in the distant past. The roughly triangular shape of the nebula can be discerned through a 6-inch or larger telescope, but HD 34078 dominates the view. Try fitting a hydrogen-beta filter to your scope to tame the star.

10. Hubble’s Variable Nebula

Also designated: C46, NGC 2261

RA 6h 39m 12s, dec. 8° 44’ 0”

Congratulations, you have reached the final object! This is the enigmatic comet-shaped nebula NGC 2261, also known as Hubble’s Variable Nebula from a series of images captured by Edwin Hubble in January 1949. The nebula changes in brightness and to a lesser extent shape, and although it is illuminated at its head by the T Tauri variable star R Monocerotis, its variability doesn’t exactly match that of the star. This unusual behaviour is caused by dust clouds orbiting close to the star, blocking its light and casting shadows across the nebula. Located 4.4° south-south-west of mag. +3.3 Alzirr (Xi (ξ) Geminorum), it is visible in a 4-inch telescope, though the nebula’s curved wedge shape is more clearly revealed through an 8-inch telescope at around 120x magnification.

RA/dec. positions are correct for J2000.0

Steve Richards is an experienced astronomer, astrophotographer and our expert Scope Doctor.