The Sky at Night TV show, past, present and future

Inside The Sky at Night

As this month’s show looks at exoplanets, Emma Johanna Puranen reflects on how alien worlds bring science and science fiction together

In just a generation, humanity has gone from knowing of a handful of planets – those in our Solar System – to confirming the existence of over 5,000. While many of these newly discovered exoplanets remain invisible, detected not from their own light but through their effects on their host star, that hasn’t stopped scientists and artists alike from understanding and imagining them not as mere data points but as fully-fledged worlds.

My own love story with exoplanets began in a car park atop Kitt Peak, a mountain in the Arizona desert that’s home to around two dozen telescopes. It was July 2013 and I was a teenager at Astronomy Camp, using the Kitt Peak Visitor Center’s Roll Off Roof Observatory to observe a transit of TrES-3b, a puffy gas giant planet with a blisteringly short year of just 31 hours. As the telescope imaged the star, I went outside and laid down on the asphalt, which still warmly radiated the heat from the day. I’d never been to a dark-sky site before. Seeing the stars in all their glory, I felt dizzy, like I had to clutch at the ground around me or else I’d fall up into the heavens. As I lay, I thought of ‘my’ hot Jupiter out there, passing between us and its sun. I wondered how many other stars in my view hosted invisible planets. I wondered what they would look like from orbit, or from their surfaces, if they had them. I wrote stories in my head about these new types of worlds.

A meeting of minds

Nearly 10 years (and 4,000 confirmed exoplanets!) later, I am a PhD student at the University of St Andrews Centre for Exoplanet Science. My research is interdisciplinary; I study portrayals of exoplanets in science fiction. In particular, I use data science methodology to look at how scientific concepts like exoplanets flow from scientists to the public through the intermediary of science fiction. Building up an entire world, from its physical environment to its biology (if it has any), is a labour-intensive process, and authors often do a lot of research. I consider questions like: where do writers get their scientific information from? How do they make decisions on where to remain scientifically accurate and where to make things up? What might science fiction look like if the writer had a dedicated science consultant?

And so I conceived a project. I paired scientists in fields from astronomy to earth sciences with writers from the university’s School of English. Each pair created a science fiction story based on the scientist’s research. Through questionnaires filled out by all the participants, I learned about their thought process as they constructed their worlds. Participants expressed how they wanted their stories to inspire readers to go and learn about strange and exciting new exoplanet findings. They also wanted to convey the deep sense of reaching into the unknown that is palpable for anyone involved in exoplanet science. The resulting anthology, Around Distant Suns, features a diverse array of worlds, from a planet covered in sentient mist to one where it rains graphite, and another that is the rocky core of a gas giant that has had its atmosphere stripped.

Most importantly, the collection highlights the ways we all yearn to engage with exoplanets. These worlds represent the big questions that all of us – scientists, artists and everyone else – are asking: what is out there, past the edge of the known? With every new planet, we are closer to knowing.

Emma Johanna Puranen is a PhD researcher with the St Andrews Centre for Exoplanet Science

Looking back: The Sky at Night

11 April 1981

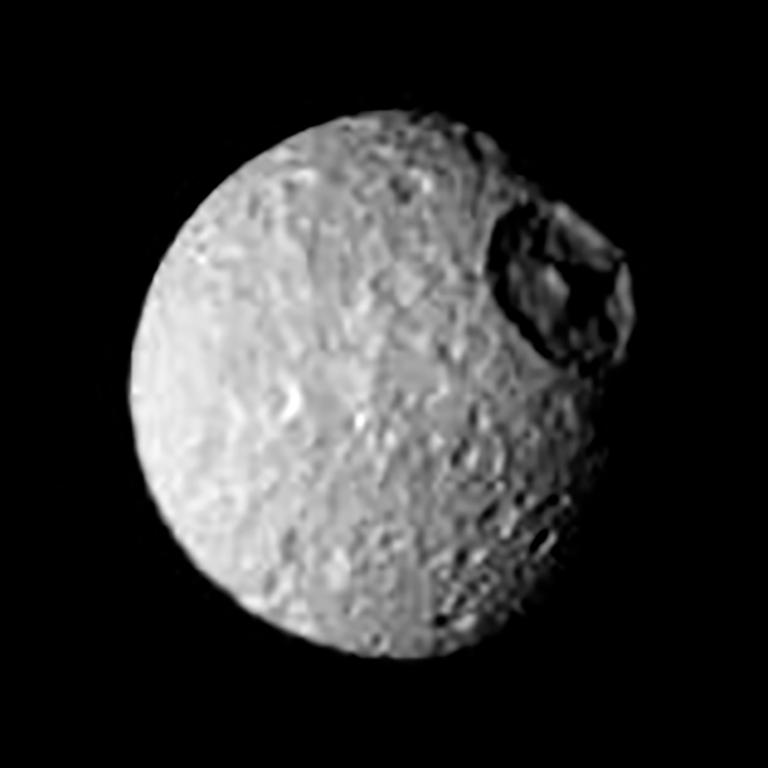

On the 11 April 1981 episode of The Sky at Night, Patrick Moore looked towards the moons of Saturn. The previous November, Voyager 1 had given humanity its first close-up look at these frozen worlds, and the show aired just as NASA had begun to publish maps created from its images.

Voyager 1 captured the surfaces of Tethys, Mimas, Rhea, Dione and Enceladus. As most of the moons were imaged from over 100,000km away, only major features were obvious, but they did reveal a large crater on Mimas (giving it a striking resemblance to the Death Star from Star Wars). Fortunately, Voyager 2 would be able to give them all a second look when it arrived in the system that August. Voyager 1 did pass much closer to one other moon – Saturn’s largest, Titan – but its thick, haze-filled atmosphere blocked the view from its optical cameras. It found that the moon was 5,150km across, making it the second-largest in the Solar System (after Jupiter’s Ganymede), and slightly bigger than the planet Mercury. It also found the surface pressure was 1.6 times that of Earth and contained organic chemicals like ethane and acetylene, but was a frigid 180ºC. At that temperature, it could well be possible for liquid methane lakes and rivers to exist on the surface, but planetary scientists would have to wait until the Cassini–Huygens probe arrived in 1997. Using its radar, that craft was able to pierce the haze and finally map out Titan’s river-carved surface.

The Sky at Night

APRIL

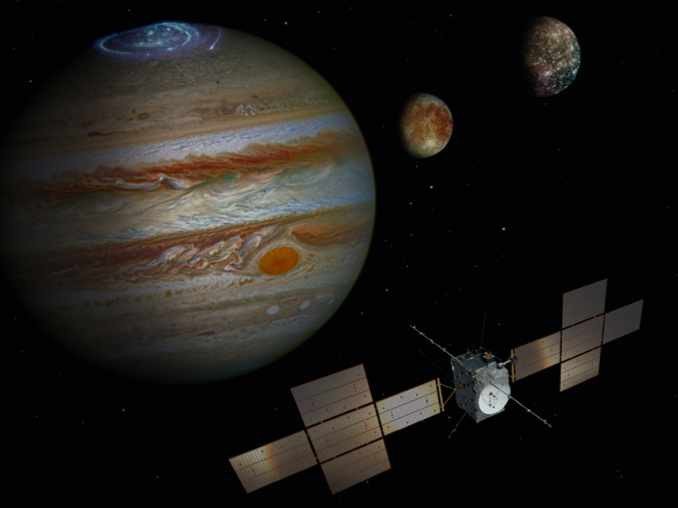

Searching for Alien Life The launch this April of the JUICE mission to Jupiter and its icy moons marks a new era in the search for habitable conditions beyond our planet. The Sky at Night meets scientists who are collecting samples from Mars, exploring the Jovian system and beyond to find out how we’re looking for extraterrestrial life – and whether we’ll know when we’ve found it.

BBC Four, 10 April, 10pm (first repeat will be on BBC Four, 13 April, 7pm) Check www.bbc.co.uk/skyatnight for more up-to-date information

Find out more about ESA’s JUICE mission to explore Jupiter’s icy moons here.