Our disappearing dark skies

Shaoni Bhattacharya looks at what is – and isn’t – being done to help ensure everyone can see the stars

The stars have always been part of human culture. From motifs on Greek pottery to van Gogh’s Starry Night painting, the connection is evident across the globe. But today, there are few people who get to experience what our forebears saw every night in the sky, researcher Christopher Kyba tells me.

“If you went outside at night you would have had the whole cosmos staring down at you – this really difficult to understand thing,” says Kyba. “From my experience with stars, it makes you quite reflective. It changes how you think – this confrontation with awe.”

The light pollution from humanity’s use of lights at night is reducing the number of stars we can see. Year on year it worsens, threatening our connection with the night sky, not to mention the implications for astronomy, wildlife, health, the climate and energy wastage.

To the human eye, the night sky is brightening by about 10 per cent a year, according to a recent study in Science by Kyba, a physicist at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, and his colleagues. At this rate, a child born in a location where 250 stars are visible at night would only be able to view 100 by the time they reach adulthood at 18. “That’s a really fast and dramatic change,” says Kyba.

He and his colleagues attribute this decrease in star visibility to ‘skyglow’ – an artificial twilight caused by streetlights, LED signs and residential lighting, scattering off molecules in the atmosphere. While most of this light escapes into space, some of it bounces back down towards Earth.

“When you see the sky is really bright, it’s a visual indicator of waste. If you’re concerned about the climate, it should concern you”

Measuring the dark

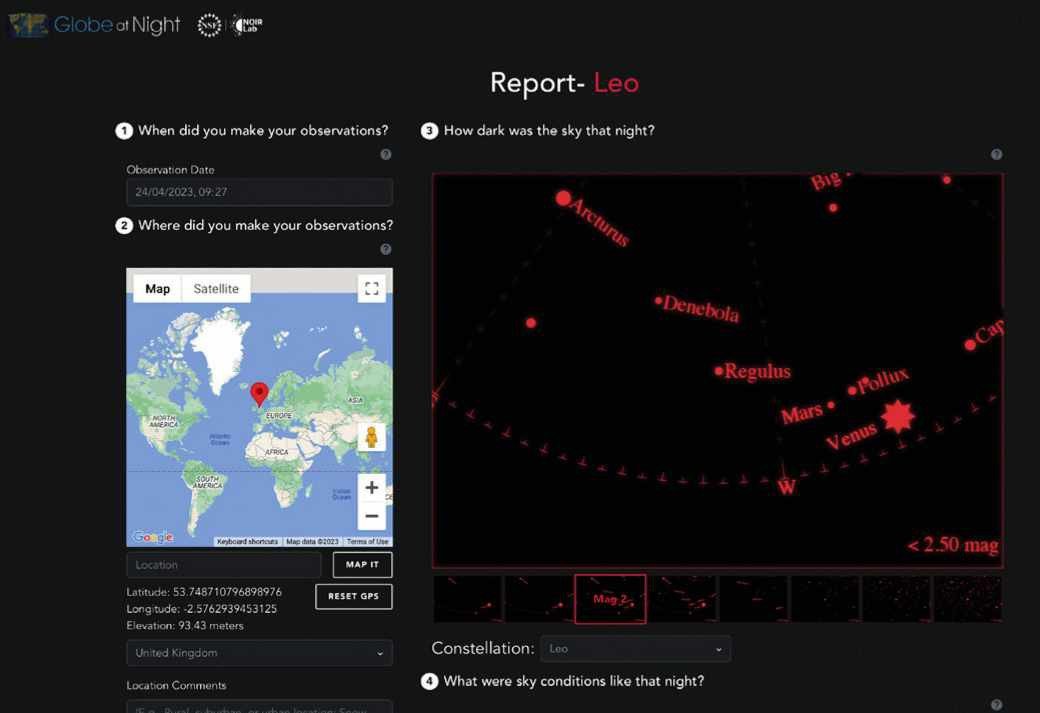

Their research draws on data collected by the ongoing Globe at Night project run by the US National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab based in Tuscon, Arizona, which amassed over 51,000 observations made by citizen scientists around the world between 2011 and 2022. Volunteers compared their naked-eye view of the sky at night to a set of star maps, to find what was the faintest star visible. This helped gauge the skyglow, as the brighter the background becomes, the more that faint stars are rendered invisible to the unaided eye.

“What we found is that the charts that people are choosing are rapidly shifting towards the charts that have fewer stars,” says Kyba.

In fact, the data showed the fall in the number of stars visible was equivalent to an average increase in sky brightness of 9.6 per cent a year, averaged over their locations – a rate very much larger than the previously measured annual increase of 2.2 per cent. This had been measured by satellites, which in principle can measure skyglow – but with limitations. Currently, Earth-monitoring satellites can’t detect wavelengths shorter than 500nm, and yet this type of light scatters more effectively in the atmosphere. Modern LED lights also peak in the blue end of the spectrum, between 400nm and 500nm, and our eyes’ sensitivity shifts towards shorter wavelengths at night. The team speculates the move towards more energy-efficient LED outdoor lighting during the 2010s may have had an impact.

The caveat here is that Kyba’s team are interpreting sky brightness rather than measuring it directly, but it seems certain that people are reporting fewer stars. That should be a concern for everyone.

“When you look outside at night and see the sky is really bright, it’s a visual indicator of waste. If you’re concerned about climate issues, if you’re concerned about energy consumption… then this should concern you,” says Kyba. He adds that the increased brightness means humans are shining more light into habitats like wetlands and waterways at night, most likely affecting wildlife.

Light pollution is such an issue that the government in the UK, along with other nations, has begun looking at policies around lighting. Tackling the issue is complex, though, as many people – from individuals to shopkeepers and local authorities – make decisions about light use at night. However, there may be a role for formal restrictions on lighting, says Kyba. For example, the energy crisis caused some places in Germany to require that illuminated signs be turned off after 10pm.

Ten-point plan to protect dark skies

The APPG’s proposals to tackle light pollution have been knocked back

1. Strengthen the National Planning Policy Framework, which helps designers constructing new developments to control obtrusive light.

2. Expand the scope of planning permission to include exterior lighting, similar to current rules around installing external advertising.

3. Limit exemptions to Statutory Nuisance Provisions, which give local authorities some power to regulate light that is ‘prejudicial to health, or a nuisance’. There are many exemptions and many venues only have to comply if it is ‘practicable’.

4. Create a Commission for Dark Skies to oversee compliance.

5. Set lighting standards for brightness and colour – such as the amount of blue light in lighting spectrums – and encourage best practice.

6. Set standards for the density and direction of lighting, including requirements around dark-friendly lighting.

7. Design a national programme of ‘Dark Sky Hours’ when lights can either be dimmed or turned off.

8. Appoint a ‘Minister for Dark Skies’ with a remit to control and prevent light pollution.

9. Create a ‘Dark Skies Towns and Cities’ initiative where local authorities have the power to cut light pollution.

10. Work with schools and organisations to educate and raise public awareness of light pollution.

Light-fighting laws

Within the UK, changes in national legislation to combat light pollution have been proposed by a committee known as the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Dark Skies (APPG). This group was set up in January 2020 to protect the UK’s night sky by Lord Martin Rees of Ludlow, the Astronomer Royal and a former president of the Royal Society, and Andrew Griffith, MP for Arundel and South Downs – a constituency that includes the South Downs Dark Sky Reserve.

After consultation with over 170 academics, astronomers, national park associations, legal professionals, members of local and national government and lighting professionals, the group published its Ten Dark Sky Policies for Government in December 2020.

“The APPG has a fairly broad remit,” says Lord Rees. “Simple energy-saving measures like tightening some of the planning laws about floodlighting stadiums and things of that kind can make them less of a nuisance and avoid brightening the sky unduly.”

The committee’s policy plan suggests 10 major changes which involve either bolstering existing planning and statutory nuisance laws, ‘supercharging’ standards for lighting, with legal clout and penalties for non-compliance, as well as encouraging best practice and incentivising dark-sky initiatives.

“The fundamental thing is that [light pollution] is recognised as a pollutant that needs to be controlled under regulation,” says Robert Massey, deputy executive director of the Royal Astronomical Society, as currently the UK does not have “hard-nosed legislation” on light pollution.

And the problem, he says, is huge. In the UK, a similar project – the annual star count run by the British countryside charity CPRE – has shown a steady increase in light pollution over the last decade, barring a small dip during the pandemic when many councils, retailers and industrial facilities shut off their lights.

Go-slow government

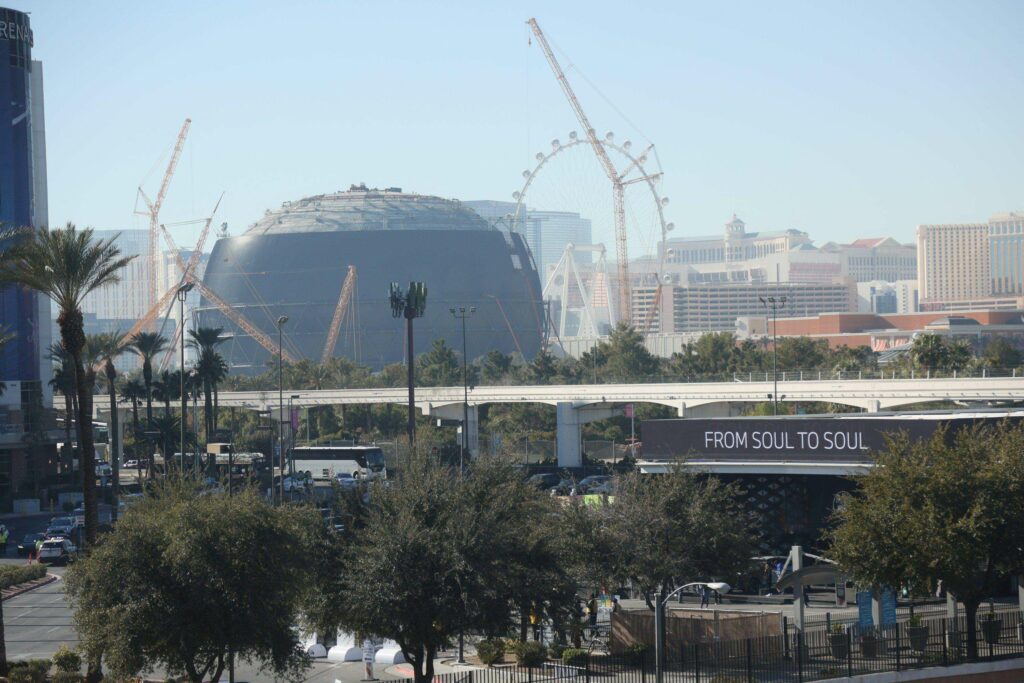

In February, Massey gave evidence to the Greater London Authority on the potential light pollution from a giant, LED-studded entertainment dome planned at Stratford in London called the MSG Sphere (Las Vegas residents close to a sister venue have warned it will be like ‘a Sun on Earth’). It’s the first time that he has been called for evidence in this way. “The fact that there were discussions on it is welcome,” Massey says.

But it appears that the UK Government is not moving on the APPG’s plan. “The Government considers the existing measures are sufficient to manage the problems caused by artificial light and there are no current plans to revise them,” said Rebecca Pow, Parliamentary Under-Secretary, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) on 25 January this year. “Defra also continues to review emerging evidence on the impacts of light pollution on biodiversity.”

While they may have to accept that the government has other priorities at the moment, says Lord Rees, “it’s our job to raise these issues on the public agenda”.

A loss for humanity

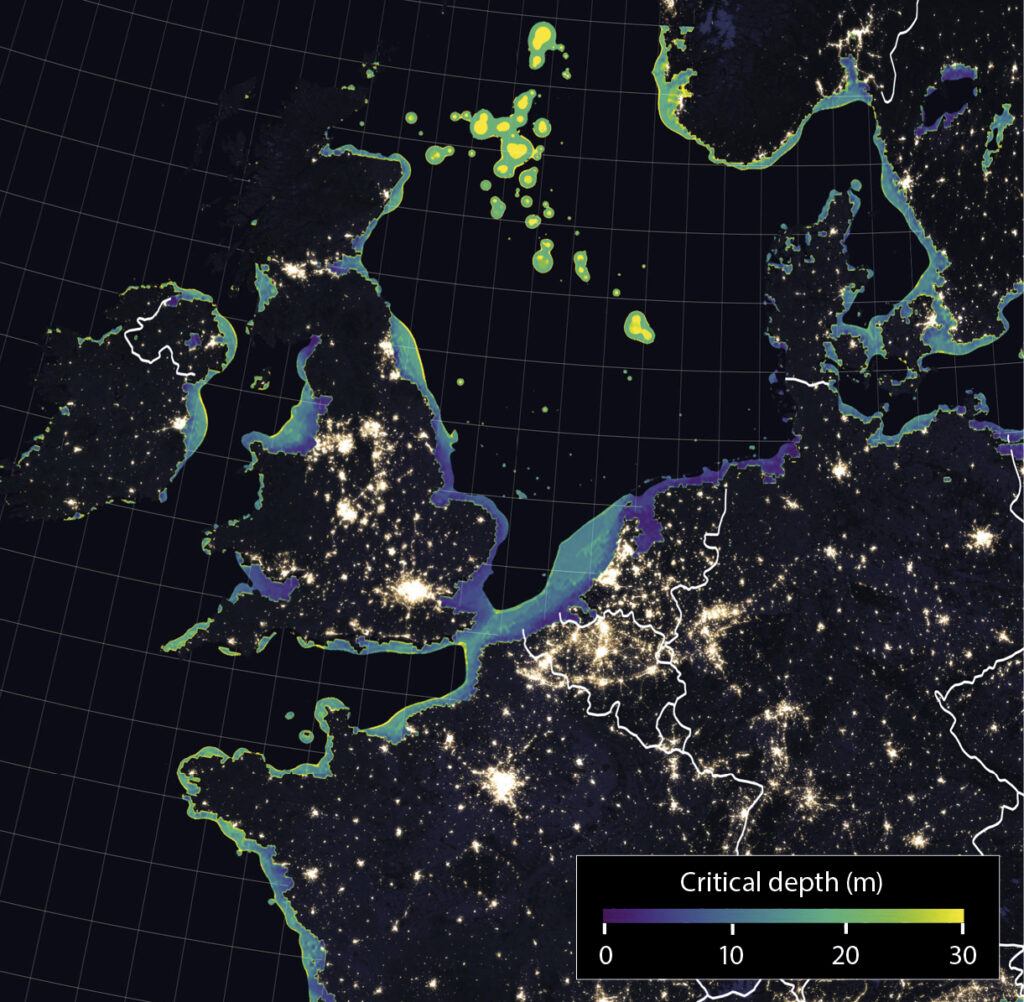

The APPG is continuing to listen to the evidence on the effects of light pollution, including the research on insect living patterns and on marine life, which is affected by human-made light as much as 30 kilometres out to sea. But while the impact on astronomy, health and wildlife is important, losing our ability to see stars may underscore a more spiritual loss for humanity.

“When you think about the troubles that we have as a society… worrying about body image and all the rest of this. Well, maybe if we were to have this confrontation with awe several nights of the month, these very individual-focused things would be less of an issue for us,” Kyba says.

Most people now live under a constant glow. The only people who can experience the sky as our ancestors did are those who are wealthy enough to visit the few places that still have starry skies, or those who live in areas too poor to afford lighting.

Being unable to see the stars is a fundamental loss, says Lord Rees. “The dark sky is the most universal part of our environment because all humans everywhere in the world throughout history have looked up at the same dark sky and wondered at it and interpreted it in their own way. And so, if young people in urban areas can’t see a dark sky, there is a deprivation. You don’t have to be an astronomer to feel deprived. I’m not an ornithologist but I would feel deprived if the songbirds disappeared from my garden.”

The stars are just as much a part of our precious environment as wildlife and natural habitats, and so protecting our night sky is a matter for everyone.

What can we do about light pollution?

Join the pushback by measuring the sky quality near you

Even small, mindful contributions – such as closing your blinds at night and ensuring outside lights are on a timer and are aiming their light downwards – can help improve light pollution, as can campaigning on projects with harmful impacts. Becoming citizen scientists with the ongoing Globe at Night project helps create the evidence to inform decision-making.

“Your participation makes a big difference to us,” says Christopher Kyba. “When you add up 10,000s of subjective feelings, it produces really reliable data.”

This is particularly important as many current lighting standards are not scientifically-based. A study on road lighting for drivers and pedestrians published in Lighting Research & Technology in 2018, found that “recommendations for the amount of light do not appear to be well-founded in robust empirical evidence, or at least do not tend to reveal the nature of any evidence”.

In the UK, participants might look at charts of Orion around January/February, or Cygnus in early autumn. You can find out more at globeatnight.org.

Shaoni Bhattacharya is a science writer and editor, as well as a short fiction author