The top sights to observe or image this month

DON’T MISS

Noctilucent cloud season

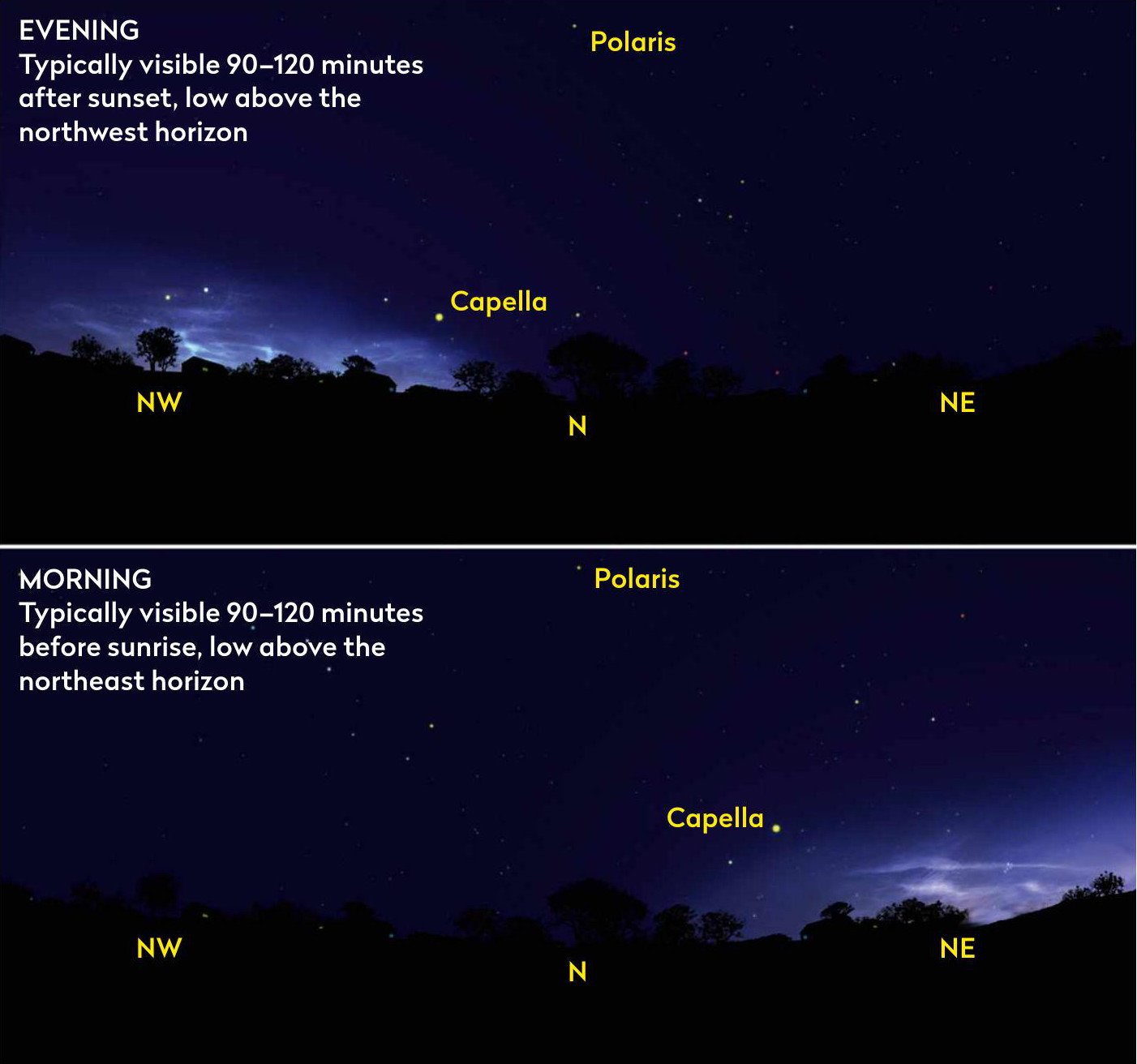

BEST TIME TO SEE: All month, 90–120 minutes after sunset or a similar time before sunrise

RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT: Naked eye

June and July are the best months to try to spot elusive noctilucent, or night-shining, clouds (NLCs). These are high-altitude ice sheet clouds that form in a narrow layer within the atmospheric region known as the mesosphere. In order for them to appear, there has to be some form of seeding agent in this layer and there has to be super-cooled water vapour present.

The theory as to how water vapour gets up into the mesosphere is complex. Once there, a super-cooled situation occurs when the temperature of the mesosphere dips below a certain threshold, which counterintuitively occurs in the summer months. NLCs can also be seen from the Southern Hemisphere during its summer period. Introduce a tiny speck of dust into the super-cooled vapour and a tiny ice crystal will form around it. In the case of NLCs, the seeding dust mostly comes from meteoroids vaporising in Earth’s atmosphere – basically meteor dust.

Being so high, at around 80km up, NLCs are still illuminated by the Sun despite it being dark for us on the ground. As a result, they become visible in the deep, summer twilight. Typically, they are visible 90–120 minutes after sunset, low above the northwest horizon, or a similar time before sunrise, low above the northeast horizon. An extensive amount of NLC ice sheet may cause a display to persist throughout the night, passing from the northwest through north and ending in the northeast as dawn breaks. What you’re seeing when this happens is sunlight following the position of the Sun below the horizon.

NLCs are often quoted as a low-altitude phenomenon from the southern half of the UK, gaining more altitude from the north of the country. This is largely true, and if your northwest-north-northeast horizon isn’t particularly flat, it’s really easy to miss them. However, NLCs have been reported at much higher altitudes, especially at the start and end of the visibility period, so it pays to remain vigilant. At high altitudes under darkening or lightening twilight, they can take on an appearance that resembles high-altitude cirrus. Make a note in your observing log if you’re not sure whether the NLCs you’ve seen are cirrus.

NLCs aren’t particularly limited by light pollution or artificially bright skies. This makes them an ideal target during the period when traditional night-time astronomy takes something of a backseat due to the lack of proper darkness.

Mars and the Beehive

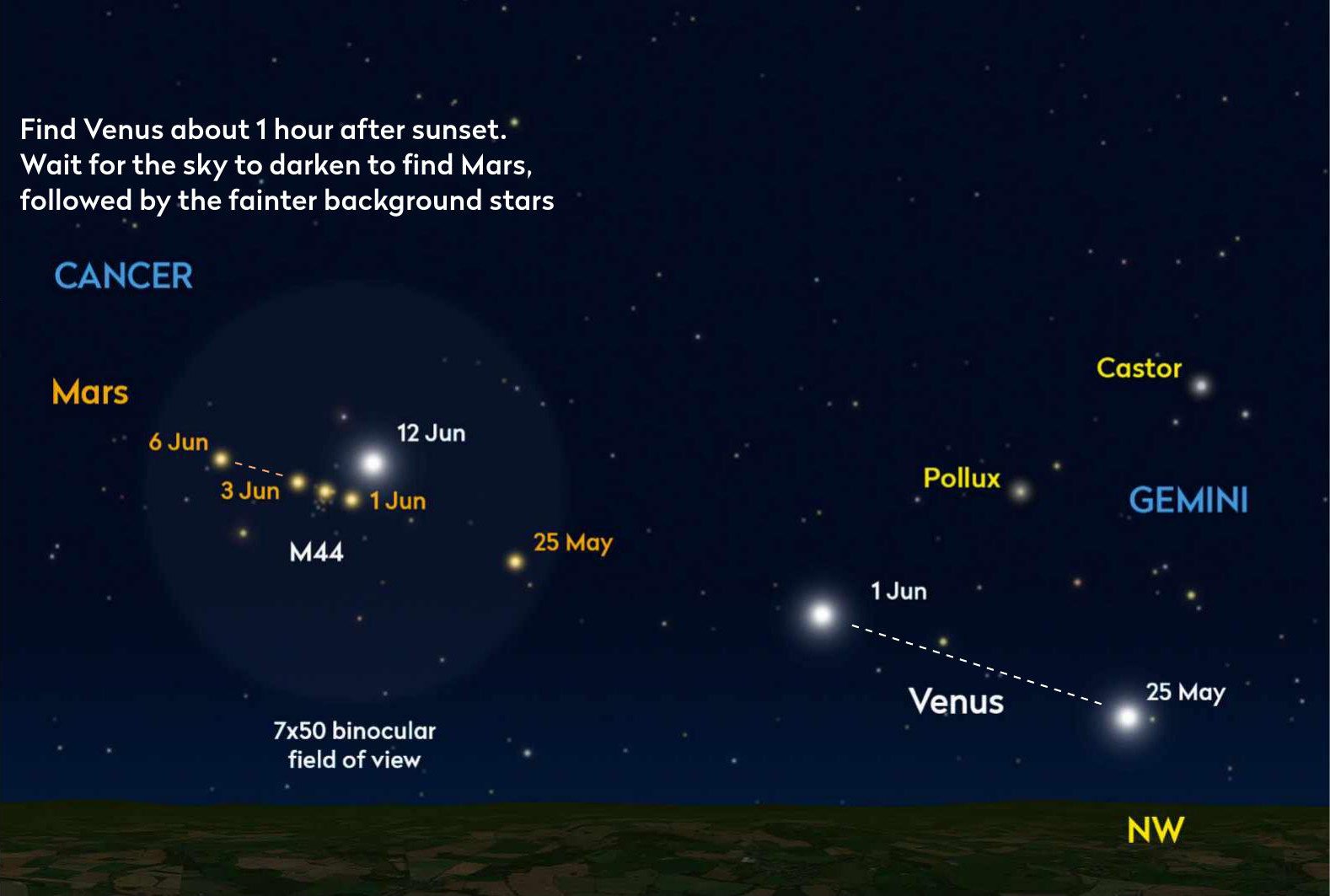

BEST TIME TO SEE: 1–3 June Mars and M44; 12–14 June Venus and M44

RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT: Naked eye or binoculars

The Beehive open cluster, M44, is a wonderful deep-sky object visible in the winter and spring sky. Its position is less than ideal during June, but despite this, during 2023 it poses an observing challenge as it’s visited by the two main planets, Mars and Venus.

The encounter with Mars is right at the start of June, arguably when M44 is easiest to see. On the evening of 1 June, as Venus gets very low and the evening twilight begins to darken enough to show stars, use binoculars to find Mars. It’s 10° to the left and slightly up from Venus, pink-orange in colour and shines at mag. +1.6. On this evening, it is located on the western edge of M44. The brighter cluster stars should be visible using binoculars given a flat west-northwest horizon. Similarly, a telescope with a camera attached, pointed at Mars, should be able to deliver the cluster as well.

A line-of-sight alignment means that Mars appears within the cluster on the evening of 2 June and slightly to the east of it on the evening of 3 June. It’s not the easiest sight, but a rewarding challenge given clear skies. Timings will vary across the UK, so a good rule of thumb is to wait until Venus is at just over 2° altitude. If using binoculars with a 5° field, the horizon should just be showing at the bottom of the field of view when Venus is centred.

The Venus–M44 encounter occurs on 12–14 June, Venus passing just north of the cluster. Bright twilight and low altitude will make this a tough observation. If you managed to see Mars and M44 earlier in the month, then you’re already prepared for just how difficult this can be.

Mars and Venus

BEST TIME TO SEE: 21, 22 June then 29 June–2 July

RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT: Naked eye or binoculars

The encounter between Mars and the Beehive, followed by Venus and the Beehive (see Mars and the Beehive, above), suggests that both planets are in the same part of the sky after sunset. Shining at mag. –4.3, Venus reaches greatest eastern elongation on 4 June, but despite its prominence in the evening sky over the past weeks, it is dropping in altitude after sunset. At that brightness it’s still easy to see, though, and a good pointer to the much dimmer planet Mars, which shines at mag. +1.7 towards the end of June.

On the evening of 21 June, Venus and Mars will be joined by a slender 12%-lit waxing crescent Moon, a lovely evening scene to mark the day of the June solstice. On 22 June, the Moon will have increased in phase to 19% and sits further to the east of both planets. Venus and Mars will appear slightly closer on this date, appearing separated by 4.5° on 21 June and 4.3° on 22 June.

Both planets continue to approach one another to reach a minimum separation of 3.6° between 29 June and 2 July. This makes them an ideal binocular target, but a flat west-northwest horizon is essential. Look out for Regulus (Alpha (α) Leonis) to the left of Mars, appearing fractionally brighter than the planet at mag. +1.3.