The Sky at Night TV show, past, present and future

Inside The Sky at Night

In The Sky at Night’s last episode of 2022, Douglas Vakoch looked into how humanity could reach out and contact other worlds

Where there is life, there is language. If you were to listen to Earth from the skies, you might hear one of 7,000 languages, and you would be forgiven for thinking only humans had evolved language. But you would be wrong.

Chimpanzees gesture instructions and emotions, whales sing to each other, and prairie dogs have vocal warnings so complex that experts believe they can describe the size, shape and colour of the threat to their clan. Life’s capacity for language astounds me, and it gives me hope. Hope that life orbiting around distant stars may also have the capacity for language and communication.

So the question is not, “Do intelligent aliens exist?” but, “Could we communicate with them?”.

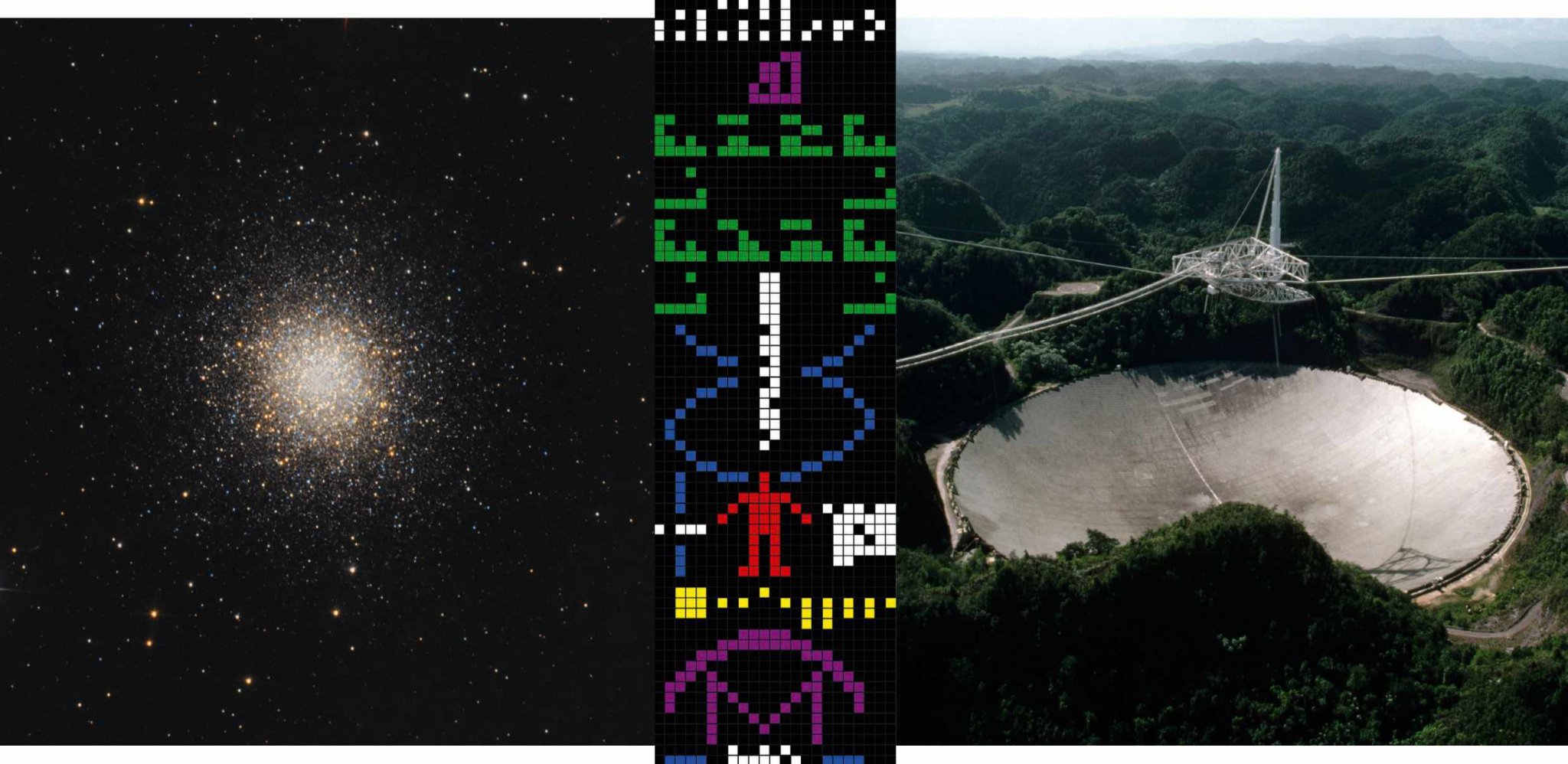

In 1974, my friend the late Frank Drake sent a message to a distant cluster of stars from the largest radio telescope in the world, known today as the Arecibo message – the first radio message to aliens. At the time, what Frank sent was the result of a phenomenal effort to create a succinct interstellar postcard and then communicate it in the best way he could think of – through the universal language of maths and science. He used binary code across two different radio frequencies to communicate how we count, the structure of the DNA molecule, what humans look like, and much more.

I was a teenager back then and was inspired by Frank’s ingenuity. When I grew up, I eventually joined Frank’s team at SETI – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Over the years I started to think of ways we could create and transmit a much wider range of new messages that could stand a better chance of being understood by intelligent lifeforms. And so, in 2015 I created METI International to do just that.

Art to the stars

METI stands for Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence, and its messages are treasure troves of science, art, and human nature, with many different ways to unlock their secrets. As we send the periodic table of elements, we talk about the chemical building blocks of the Universe – something scientists on another planet will also understand. We use maths to describe beautiful shapes that are built into nature, like the spiral of the nautilus shell. And we create interstellar morality plays that start telling aliens what it’s like to be human. We’ve designed our messages so that any alien species that is capable of receiving radio signals could decipher and understand them.

There is one more critical difference between METI’s messages and Frank’s: the stars we target. In 1974, Frank sent his message to a distant cluster of stars in Hercules, known as M13. This globular cluster is so far away that if SETI were to receive a response to the message, it would take 50,000 years to arrive. Who even knows if we’ll still be here to accept it? We can do better than that and so, in contrast, METI sends its messages to stars much closer to home. If our messages are received, deciphered and replied to, we could receive a response in as little as a decade (if we are lucky).

If extraterrestrials do get our messages, will they understand them? And what will they say back? Will they use the language of binary numbers? Will they show us what they look like? Will they tell us what they find beautiful? Will they say hello? To me, this is the real mystery. What message will they transmit back from their distant star? With METI, and a bit of patience, we now have a way to find out.

Douglas Vakoch is president of METI and editor-in-chief of Springer’s Space and Society book series.

Looking back: The Sky at Night

18 February 1976

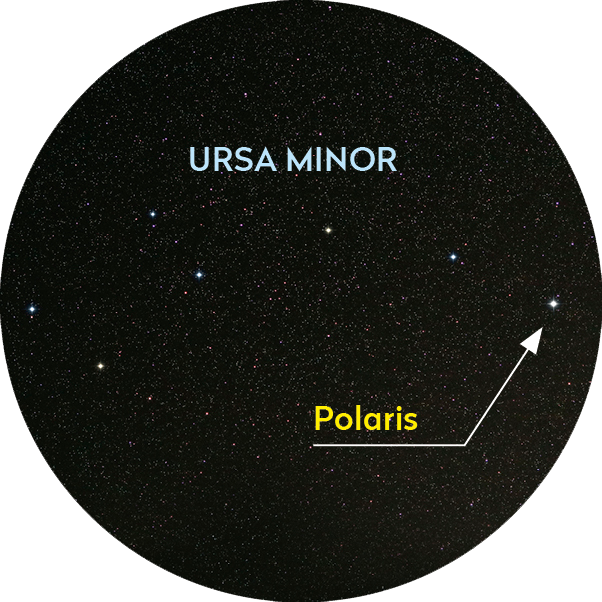

On the 18 February 1976 episode of The Sky at Night, Patrick Moore looked towards a star famed not for its brightness or scientific importance, but its position – Polaris, the North Star.

Located over the north celestial pole, Polaris is one of the first stars most people learn in the night sky, and from his home in Selsey, West Sussex, Patrick taught viewers how to locate the star. It is a common misconception that Polaris is one of the brightest stars in the night sky, but in truth it ranks around 50th (it’s a variable star, meaning its exact ranking is hard to pin down). It is a mag. +2.0 star, meaning it’s visible to the naked eye in all but the most light-polluted places, and is in the tail of Ursa Minor. The Plough asterism in Ursa Major points the way for stargazers, as the stars on the end of the ‘blade’ line up almost perfectly with Polaris.

Patrick related the star’s historic importance during the episode. As it is near the north celestial pole, it remains a fixed point in the sky as Earth rotates beneath it, an effect navigators have used to find north for centuries.

However, while it appears to remain fixed over our lifetimes, the star is actually drifting due to precession, where the axis of Earth shifts over 26,000 years, causing the pole star to change. Thuban was used to align the pyramids 4,500 years ago, while in 1,000 years’ time Gamma Cephei will take over, followed by Cepheus, Deneb and Vega before coming back to Thuban.

CBeebies Stargazing

There is no episode of The Sky at Night in February, but there is a wealth of astronomy and stargazing content on the BBC iPlayer that’s suitable for children and young astronomers. The CBeebies Stargazing Grand Tour sees Maggie Aderin-Pocock and Chris Jarvis embark on a journey across the Solar System, inspired by the Voyager missions of the 1970s and 1980s. In each episode the team jump onboard their Space Sailor and explore a different planet, revealing the spectacular science behind the worlds of our cosmic neighbourhood. www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000rjgl