The amateur astronomer’s forum

Field of view

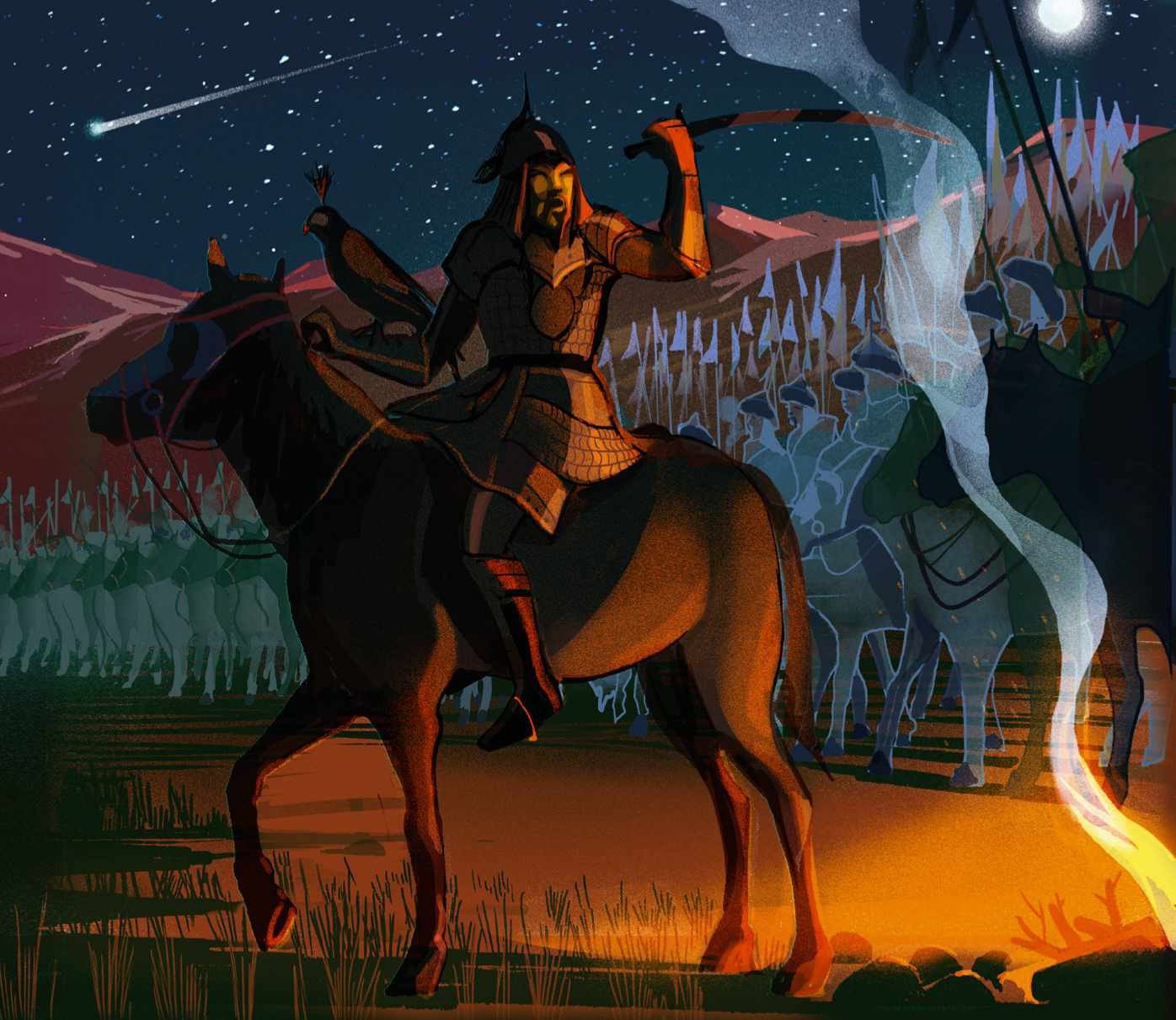

When the cosmos changes history

Jonathan Powell tracks celestial events that have altered world affairs

There are those who have been fortunate to experience marvels when looking skyward – a total solar eclipse or the Northern Lights in all their glory – or perhaps they’ve been lucky enough to find a lens cap on the ground in pitch-dark conditions. However, there are some astronomical showstoppers whose magnificence has gone down in history.

Comets feature significantly in this category down the centuries, such as the Great January Comet of 1910, often referred to as the Daylight Comet, which matched Venus for brightness with its appearance in the daytime sky. Comet Ikeya-Seki dazzled too in the daytime of October 1965, while Comet McNaught also produced a more than decent show, visible in January 2007 in broad daylight.

Well before these more recent showings, we can thumb back through history to 1222. In that year Genghis Khan looked up into the heavens and spotted a blue streak pointing west, which he declared to be his own personal star (it was in fact Halley’s Comet). He took the appearance as heavenly approval to sweep his armies through medieval central Asia. So, he did.

Just imagine if an eclipse were to take place during a dramatic battlefield scene, when two great opposing armies were ready to begin manoeuvres. Such an event did occur, when the Medes, an ancient kingdom with roots in modern-day Iran, confronted a neighbouring kingdom to the west in modern-day Turkey, the Lydians. At the Battle of Halys in 585 BC, a total solar eclipse was to stop both warring parties in their tracks. Such was the dramatic impact of the eclipse that peace ensued, with both parties thrashing out a treaty to end hostilities for good.

From a solar eclipse to a lunar eclipse, and none other than Lawrence of Arabia. In 1917, as the Arabs revolted against the Ottoman Empire, Lawrence and his troop of 50 Bedouin soldiers made their way across the desert sand dunes to engage with Ottoman forces holding the city of Aqaba. However, his army was fretful of making a night attack with a full Moon illuminating the landscape. Lawrence, who was aware of the impending lunar eclipse, was able to quell their fears by telling them that there would be no full Moon for a time. He was right and when the eclipse occurred, the Ottoman army were duly spooked, and Lawrence’s forces were able to capture the city a short time later.

Despite being widely recorded, supernovae seem not to have had a great influence on historical events, bar the event itself. Looked upon as ‘temporary stars’, history speaks of two potential occurrences as far back as 185 AD and 393 AD. The first was recorded to have been on view for 20 months, the second for eight months. In subsequent centuries, supernovae have also been recorded in 1006, 1054, 1181, 1572 and 1604, all putting in decent showings, observable for between six months and up to three years.

It’s a thought to ponder that these astronomical events, taking place at these great distances, can have such an influence on life here on Earth.

Jonathan Powell is a freelance writer and broadcaster. A former correspondent at BBC Radio Wales, he is the astronomy columnist at the South Wales Argus.