Number of stars visible by eye has dropped by 10 percent in a decade

The stars are disappearing from the night sky at a much higher rate than has been previously measured by satellites, according to a decade’s worth of measurements gathered by members of the public and analysed by scientists.

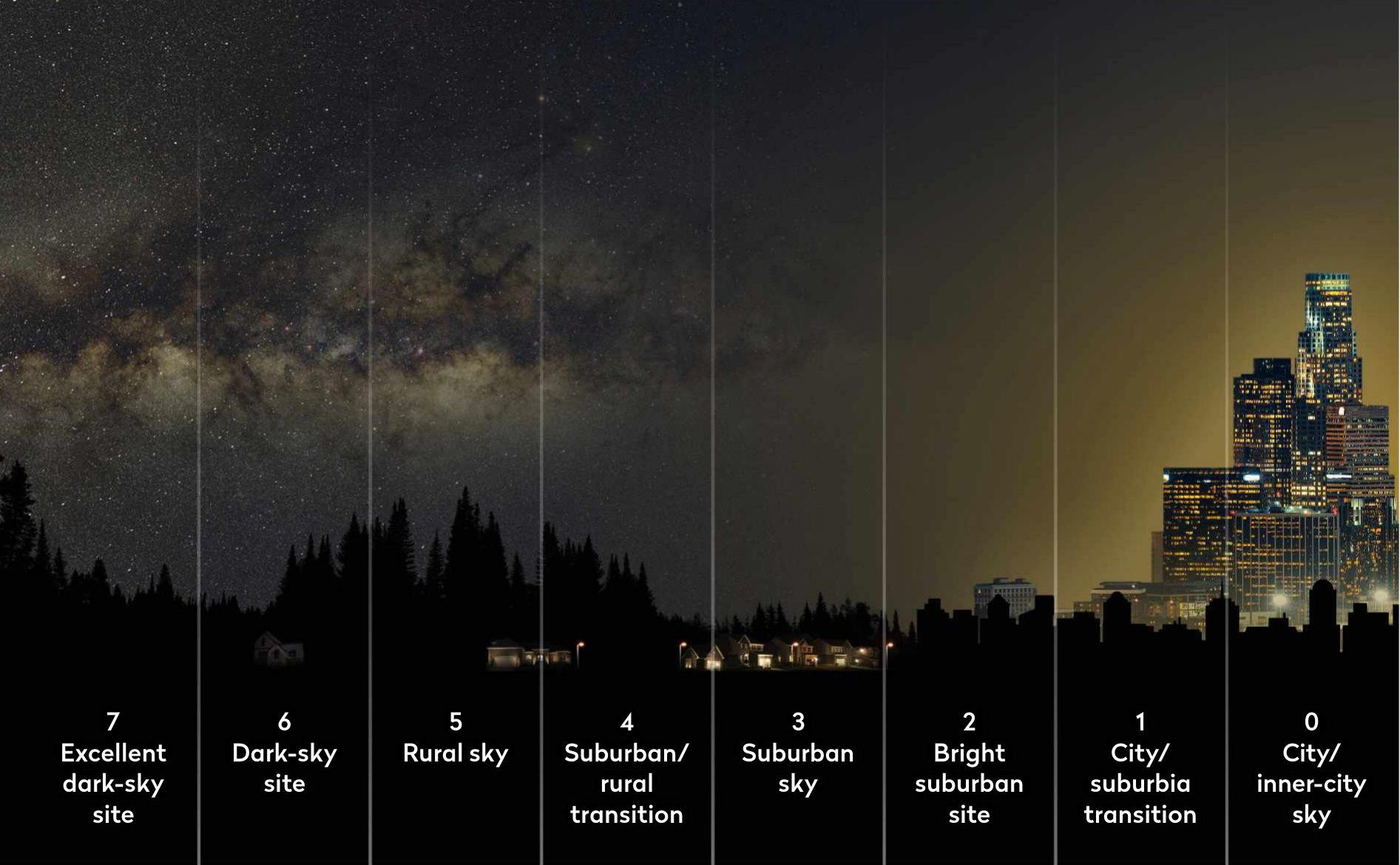

The Globe at Night programme run by NOIRLab has been gathering measurements from citizen scientists around the world since 2006. The project asks them to compare their view of the night sky to that shown on star charts, to give a rough estimate of the limiting magnitude at their location. This latest report found that in the period between 2011 and 2022, the average number of visible stars dropped by almost 10 per cent.

“At this rate of change, a child born in a location where 250 stars were visible would be able to see only about 100 by the time they turned 18,” says Christopher Kyba, one of the researchers at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences that is leading this latest analysis.

This was significantly higher than the 2 per cent drop measured by satellites, partly because they are unable to measure the full extent of skyglow, the diffuse illumination of the night sky by light pollution, which is apparent from the ground. No current satellite can measure skyglow at wavelengths shorter than 500nm – yet this blue light contributes disproportionately to skyglow as it scatters more in the atmosphere. In addition, increasingly common outdoor white LED lights peak between 400 and 500nm.

“Since human eyes are more sensitive to these shorter wavelengths at nighttime, LED lights have a strong effect on our perception of sky brightness,” says Kyba. “Existing satellites aren’t sufficient to study how Earth’s night is changing. That shows that Globe at Night isn’t just an interesting outreach activity, it’s an essential measurement of one of Earth’s environmental variables.” www.globeatnight.org

Comment by Chris Lintott

I feel surprisingly optimistic about this news story. Of course it’s unequivocally bad that light pollution is getting worse. So why am I cheerful? Because while I knew the switch to LED lights had made a big difference, I hadn’t realised things were getting this bad, this fast. Light pollution can seem an intractable problem, but if things can get worse fast, they can also improve rapidly.

We just need to persuade our neighbours, businesses and local politicians to make sure that the changes from now on are in the direction of responsible, careful lights, shining where they are needed, and not where they aren’t – up into the night sky.