The Sky at Night TV show, past, present and future

Inside The Sky at Night

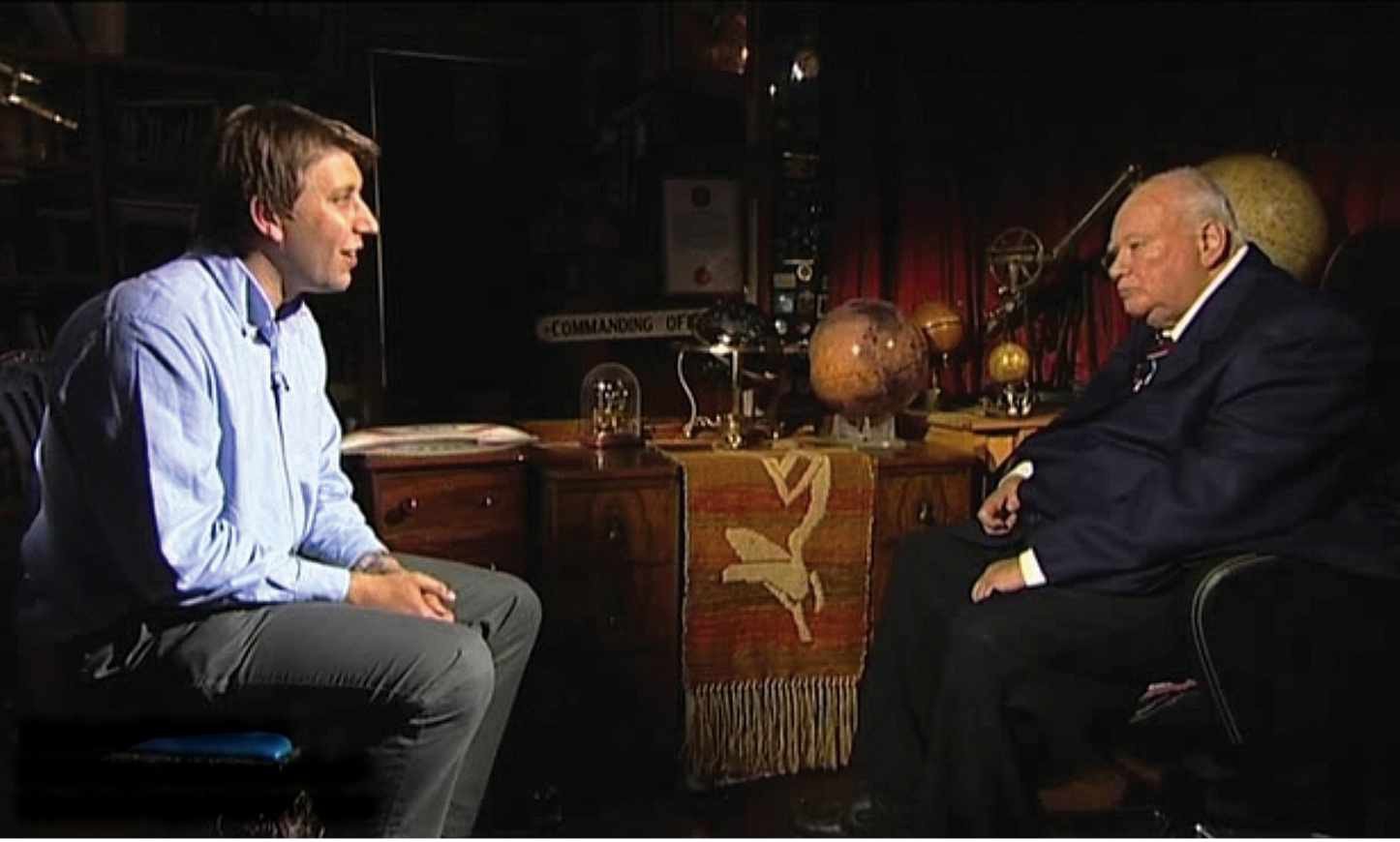

On the 100th anniversar y of Patrick Moore’s birth, Chris Lintott remembers the time they spent together on the set of The Sky at Night

A decade has passed since we made a show with Patrick. It’s hard to believe that it’s been so long. While his spirit and ideas, and particularly his determination that we should try to explain everything we can as simply and plainly as possible, still inspire us each month, I have to confess that I miss the anarchic fun that he brought to the whole process of making The Sky at Night.

Though my first couple of encounters with Patrick on the programme were in the studio, tucked away in the corner of BBC Television Centre’s enormous Studio 1, by the time I joined the show as a researcher and then reporter, its heart was the study of Patrick’s beloved home in Selsey, Farthings. Guests would travel down and stay over, making the dinner table (replete with food provided by the local pub) the site of the world’s best and most convivial astronomical tutorial. I wish we’d recorded some of those chats, which were often three or four hours long; in the era of podcasts, they would be great bonus content!

I learnt an enormous amount from those evenings, both about astronomy, but also about how to communicate. Patrick would be having a thoroughly sociable time, but then suddenly interrupt to make sure that he understood a particular point, or to express his scepticism at some modern theory (“Dark matter? Well, I suppose it’s okay…”, he would chunter). All of it went into making the next day’s conversation, on camera, flow as easily as possible, and more than one guest was surprised to find their choice description of some phenomenon or other now firmly installed in Patrick’s opening monologue.

Fun times at Farthings

Some of my favourite programmes were the times when we could open up the rest of Farthings and use the observatories in the garden. We hosted several Sky at Night star parties, where guests like Terry Pratchett – who brought his own bat detector, for some reason – could rub shoulders with astrophotographers and amateur astronomers of all stripes. It was an exhausting way to make a programme, with the long-suffering crew dealing with what now seems like very primitive night-vision equipment out in the cold for hours and hours. But we’d always come inside to find Patrick, his on-camera duties done, holding court until dawn, telling stories to others who had retreated inside.

As Patrick could travel less and less, he was extraordinarily generous with the programme, insisting it was important the show got about, even if he couldn’t. We did manage some trips though. I vividly remember him in an enormous orange boiler suit, chatting away to everyone as we descended in a lift to the UK’s dark matter experiment in Boulby Mine.

And there was also a last trip to Jodrell Bank to interview its director and inspiration, the late, great Bernard Lovell. The two old friends chatted for the camera in front of the giant dish, now named after Lovell, until it began to rain. As we rushed to finish, each was solicitous in explaining that while they, despite their advancing years, were fine, it might be a good idea to get the elderly gentleman opposite into the warm.

Patrick was often frustrated by the show. His idea of a perfect programme would usually be a 20-minute monologue, delivered with monocle in place, straight to camera, and as technology and television advanced, producers and audiences expected rather more. What he was always proud of, though, was that The Sky at Night didn’t ever waver from its original idea: to tell everyone what we know about space, and the night sky above our head, as clearly and simply as possible. He did it like no one else could.

Prof Chris Lintott is an astrophysicist and co-presenter on The Sky at Night

Looking back: The Sky at Night

4 April 1979

Back on the 4 April 1979 episode of The Sky at Night, Patrick took the time to look not at the stars but the seemingly empty space between them. While this might look like an empty void, it is actually filled with a cocktail of gases.

Early astronomers believed space was filled with ‘aether’, a hypothetical substance they thought light travelled through. It wasn’t until 1904 that the first signs of gas were detected by Johannes Hartmann while he was observing the binary star Delta Orionis. Hartmann noticed that while most of the spectral lines created by elements within the star broadened and shifted as the stars rapidly orbited each other, the calcium lines remained steady. He concluded that calcium wasn’t within the star’s atmosphere, but in the space between.

Over the years, more elements were discovered between the stars. The first molecule was discovered in 1937, with increasingly complicated ones discovered in the years that followed, including several organic chemicals – the building blocks of life. All of these various elements, however, originated within the stars themselves. While some gas escapes the star’s gravity via stellar winds, most is thrown out into the cosmos during supernovae. Over millions of years this gas drifts through the cosmos, forming clouds and structures that form the most visible sign of the interstellar medium – nebulae.

Searching Space

The Sky at Night team are taking a break this month, but will be back on our screens in April. In the meantime, explore some of the latest space science and astronomy with the Searching Space collection on the BBC iPlayer. The New Space Race takes a fascinating look at emerging private spaceflight companies, while Cosmic Hunters reveals the new technologies helping astronomers unlock the secrets of the Universe, and Return to the Moon explores NASA’s Artemis and the plans to once again put humans on the lunar surface. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0dpfs4l