Dancing lights from space

INVESTIGATING THE AURORAE

The aurorae are as beautiful as they are mysterious. Maria-Theresia Walach explains what we know about the creation of these ever-changing light shows

Dancing across the night sky, the aurorae are one of the most beautiful light shows in nature. Mysterious and elusive, they are a glorious sight, drawing people to travel to remote and frozen places in the hope of seeing them. But the lights we see waltzing overhead are only the final spectacle of a 150-million-kilometre journey of solar wind, travelling from the Sun until it crashes into our planet’s magnetic field, with spectacular results.

The journey begins at the Sun, a roiling ball of plasma. Most people are familiar with the most commonly observed forms of matter – solid, liquid and gas – but plasma is the fourth. Physicist Irving Langmuir was the first to recognise plasma in 1920, when he and his colleagues were investigating charged gases and found they could not only carry electrical charges but they could also mould themselves around magnetic fields.

The gas had become ionised, or charged, to form what Langmuir called a plasma. Atoms get ionised when their negatively charged electrons, which surround a positive nucleus, have enough energy to escape the nucleus, so that the atom becomes charged. Sunlight can ionise the uppermost parts of our own atmosphere, but by far the biggest ball of plasma in our Solar System is the Sun. It is hot enough to have an entire atmosphere made of plasma. The gravity of the Sun is not strong enough to keep all of its plasma together, so some escapes into space, streaming outwards as the solar wind.

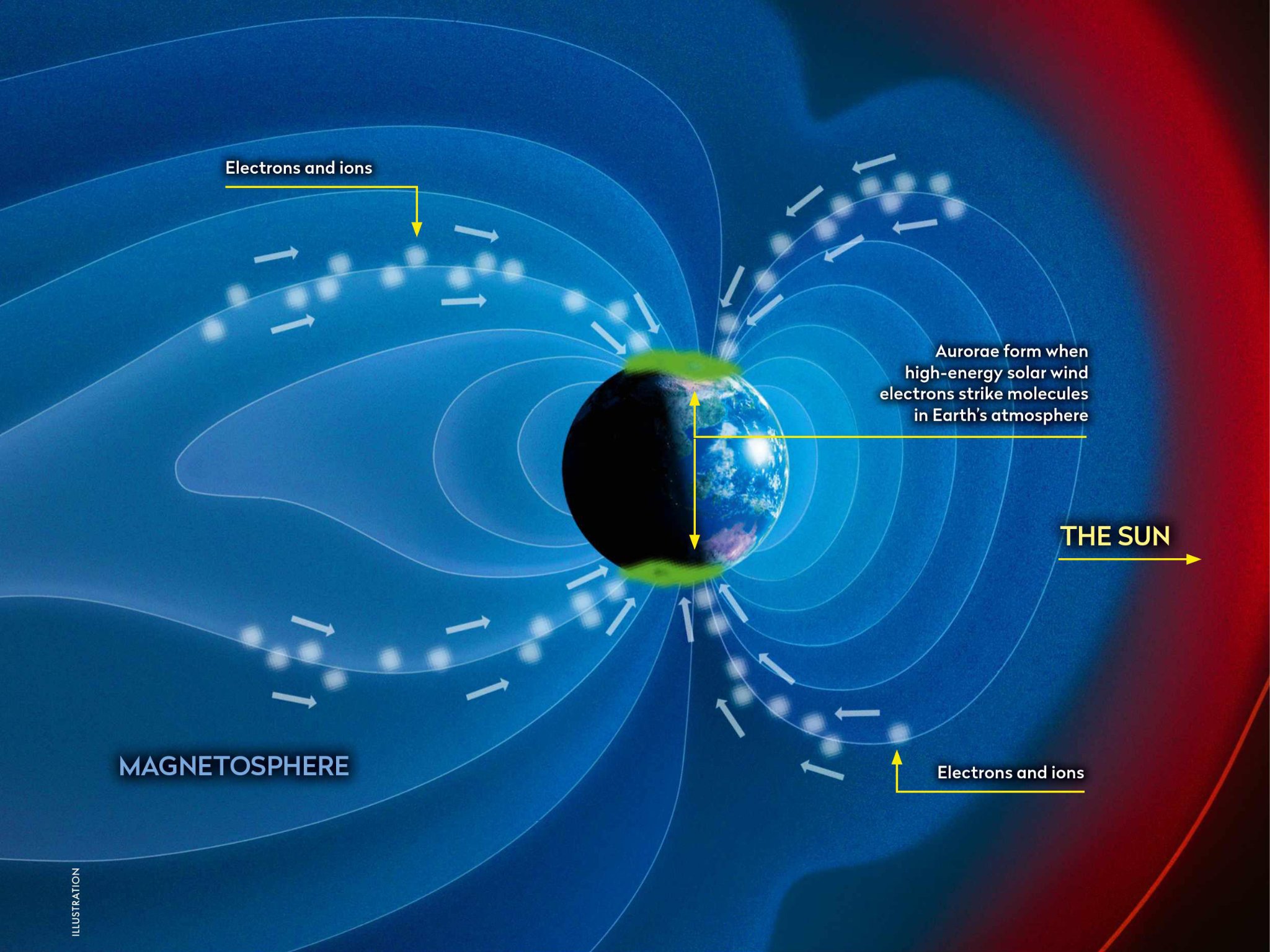

This solar wind whizzes through the Solar System, past all the planets – including Earth – carrying with it not just the Sun’s plasma, but also its magnetic field. When the wind meets our planet, Earth’s own magnetic field carves a bullet-shaped cavity into the wind, called the magnetosphere.

As Langmuir found out decades ago, magnetic fields can guide plasma movements. In the case of our magnetosphere, it guides the solar wind’s plasma around our planet, protecting our atmosphere from being swept away by making it difficult for the plasma to cross its boundary. However, there is some plasma already inside the magnetosphere, mainly originating from sunlight ionising particles in Earth’s atmosphere. This plasma is able to travel along magnetic field lines, which guide it into the upper part of the atmosphere, called the ionosphere.

Colours of the aurora

The colourful hues of the aurora come from our atmosphere’s composition

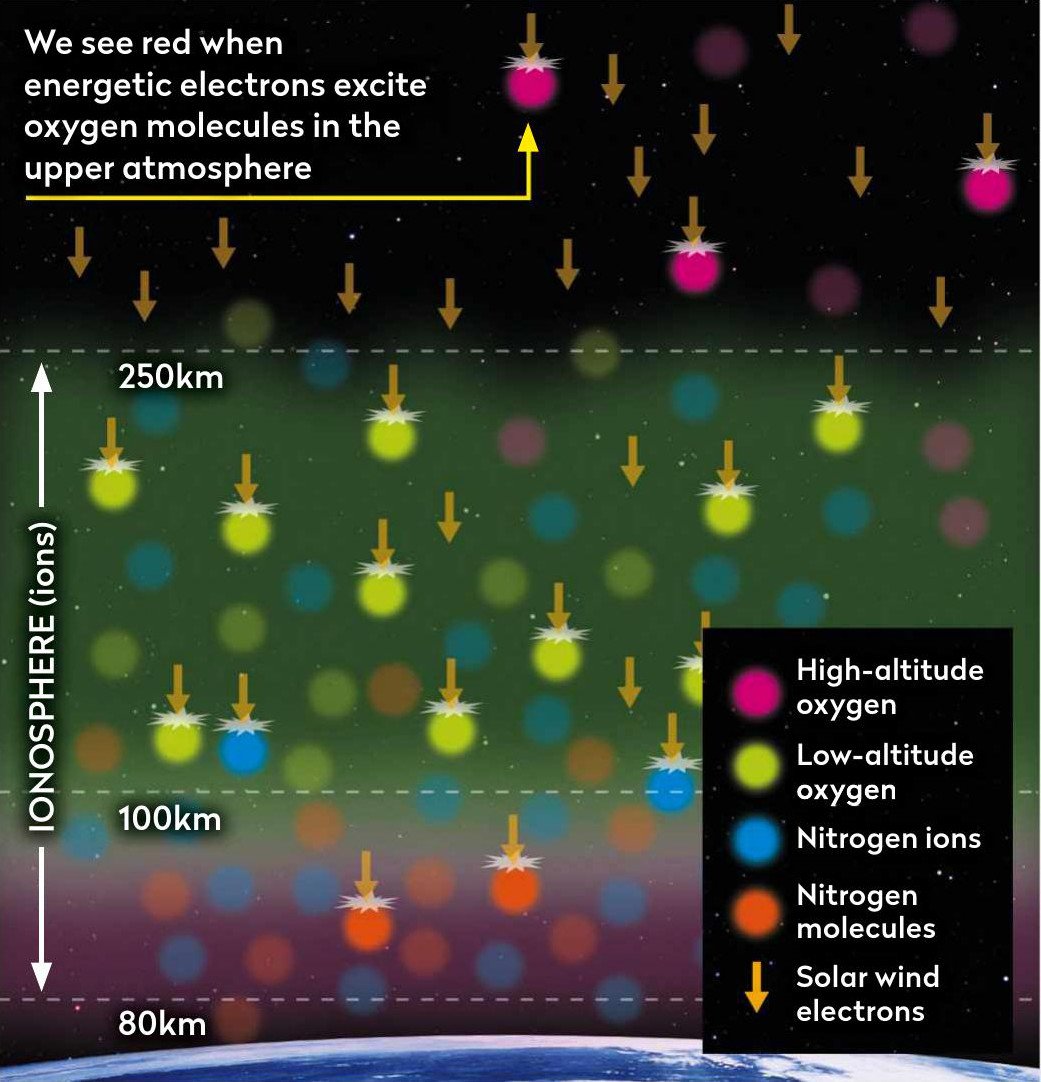

The aurorae come in many different colours. Specific colours are created when certain molecules in the atmosphere are hit by an energetic electron, causing them to emit light with a certain frequency, which is what our eyes interpret as colour. Not all of these are visible to our eyes – the ultraviolet light of the aurorae is invisible and largely filtered out by the atmosphere, but very useful for scientists.

What is visible is, however, worth seeing. The concentrations of molecules vary with altitude, so different colours are typically given off in different parts of the atmosphere. At around 200–250km, our atmosphere’s abundant oxygen gives off red light. At altitudes up to around 150km, oxygen molecule densities become much higher and they give off a green light – the most common aurorae colour you will see. Nitrogen molecules at lower altitudes can give off a blue, violet and pink light. This happens typically below 100km, where hydrogen molecules also give off a pinkish red. You might see combinations of these and – depending on the viewing angle, energy and direction of precipitating plasma – the dance of lights will be different every time.

Tripping the light fantastic

It is when these currents meet the ionosphere that the magical aurorae begin to take shape. The highenergy electrons in the plasma hit molecules within the atmosphere, transferring some of their energy. If there’s too little energy transferred, nothing happens. Too much and it ionises the atmospheric molecule, so it becomes plasma too. But if the angle and speed are just right, then the aurorae can shine. The collision makes the atmospheric molecules vibrate, which in turn causes them to radiate light. When enough of these molecules shine together, they create the beautiful aurorae, dancing across the sky.

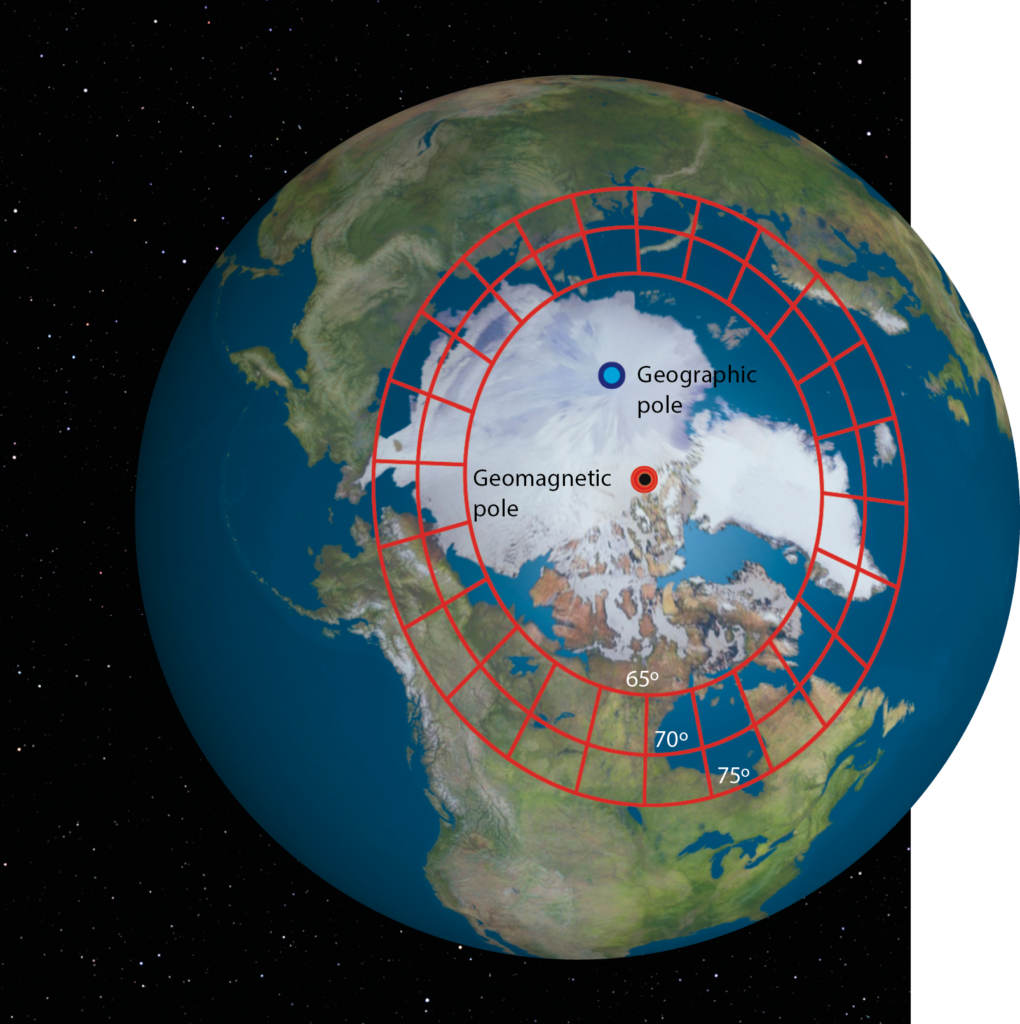

The points at which the electrical currents from the magnetosphere meet the atmosphere trace out two ‘auroral ovals’ surrounding both the northern and southern magnetic poles. On an average day, the energy in these regions is enough to create aurorae in the ultraviolet part of the light spectrum, which is invisible to the naked eye.

“If the angle and speed are just right, the collision makes the atmospheric molecules vibrate, causing them to radiate light”

Making the aurorae visible requires more energetic electrons. These can be generated through a process called reconnection, where the magnetosphere interacts with the solar wind to connect field lines that were previously separate. When reconnection occurs, it allows electric currents to carry energy and plasma across the previously impassable boundary into our magnetosphere. On the dayside of our planet, reconnection separates magnetic field lines from Earth’s field and attaches them to the Sun’s. This means a portion of our magnetosphere travels with the solar wind as it sweeps around our planet, dragged towards the nightside. Here reconnection works the other way, reconnecting our magnetic field back to Earth. During this process, the plasma gets accelerated along the field lines, giving it the energy it needs to create visible aurorae.

However, the magnetosphere is constantly changing, and the solar wind that buffets the magnetosphere is as unpredictable as terrestrial winds. Reconnection doesn’t always happen, resulting in the aurorae’s changing and elusive nature. At times when reconnection is more likely to occur, we see particularly bright and vivid aurorae as the magnetosphere’s electrical current system is amped up.

Elusive and unpredictable

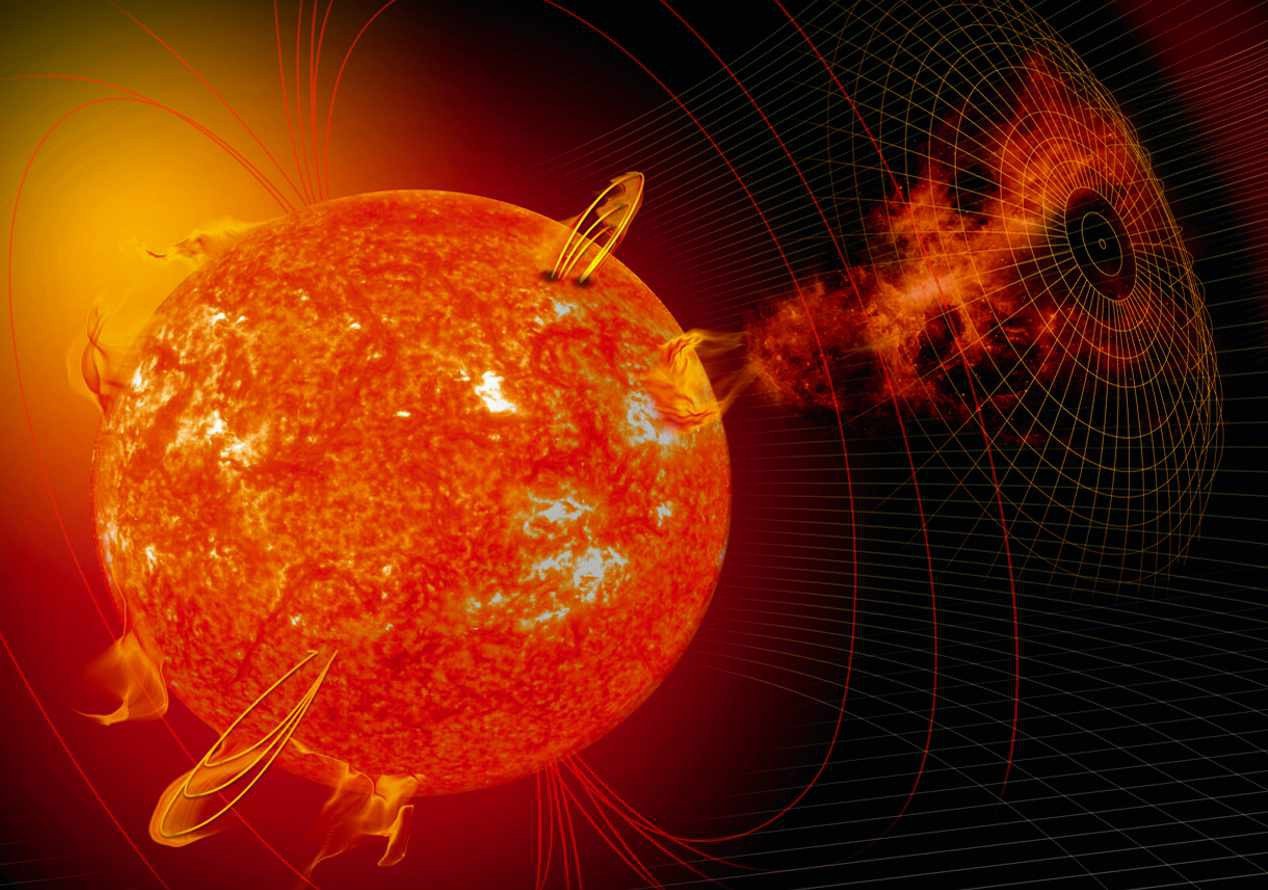

There are many things that govern the probability of reconnection, such as the angle of the Sun’s magnetic field as it hits Earth. The best alignment is when its magnetic field is pointing southward with respect to Earth. Due to the planet’s axial tilt, this occurs more frequently around the equinoxes in September and March. Reconnection is also more probable if the solar wind is blowing hard, which is governed by the activity of the Sun, though the relationship is complex and high activity does not always guarantee fast speeds. An increase in sunspots can cause more complex solar wind structures to produce faster winds. Sunspots follow an 11-year cycle, starting quietly, then building to a maximum before falling back down again. The current solar cycle is ramping up in activity, with the next maximum estimated for 2025.

The best shows come from geomagnetic storms, created by activity such as coronal mass ejections. These are very unpredictable, but they do occur more frequently around the solar maximum, and throw plasma into space at incredible speeds.

Unwrapping the enigma

The aurorae’s magical appearance is matched by their mysterious nature. Even though we know where these lights come from, there are many more questions to be answered. Precise prediction, for example, remains a challenge for scientists.

To gather more data, we use not only cameras, but magnetometers to measure fluctuations in the magnetic field, as the electric currents in the atmosphere generate magnetic fields strong enough to affect Earth’s global field. Radar receivers, based down here on the ground, can be used to measure the plasma moving in the ionosphere, giving us an idea of the aurorae’s likely location. We can also fly spacecraft directly through aurorae, or just below them – either via an orbital satellite or by flying an experiment on a suborbital rocket – but these don’t operate for long periods of time. The vastness of space means that it is unfeasible to have observations everywhere all the time, not to mention the fact that ground-based observations are far easier to operate and repair.

We have learned something about aurorae from all these observations. We know the auroral ovals can move in closer to the poles or out towards the equator depending on the balance of reconnection rates and electrical currents. What does that mean for us here on Earth? We’re still working that out. The ionosphere is the lid to the neutral atmosphere we depend on, and to fully understand Earth’s climate and atmosphere we need to know the relationship between the two. The problem is we have not yet fully understood how aurorae change the atmosphere underneath them and how and when the plasma moves. If we did, we might finally be able to predict that most elusive of astronomical phenomena – the aurorae.

Maria-Theresia Walach is a senior research associate at Lancaster University, studying the ionosphere.

How to find the aurora

To see the beautiful aurora, you first have to hunt them down

If you want to see the aurorae in person, you’ll need to start by picking either the Northern or Southern Hemisphere. As there is a greater landmass underneath the northern auroral oval, however, the Arctic circle is a good place to start, particularly when travelling from the UK. The area covers Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Canada and Alaska, so there’s no shortage of destinations.

The lights can make an appearance on any night, but there are certain times when they are much more likely to put on a great show. At the moment the Sun is heading towards the peak of its cycle, meaning that there is increased solar activity which raises the chances of some brilliant displays over the next few years. While the winter months have plenty to offer, the equinox months of September and March are usually the best.

Darkness is your friend because the aurorae are not always as vivid to the eye as pictures might suggest. A camera can help you draw out the details that your eyes might struggle to pick out.

Checking the weather radar for clouds could save you hours in the cold. While you are doing that, you can also check the geomagnetic conditions, or observe the solar wind. There are many apps that can help you do this and some even give you an alert, so you can enjoy a warm evening indoors until nature’s light show is ready for you. And one last piece of advice: if you happen to fly near to the poles, make sure you look out of the window!