Mercury returns to twilight

The inner wanderer graces our evening skies once again this month. Charlotte Daniels reveals when to look for Mercury, and what you’ll be able to see

When most beginners start out in planetary astronomy, it’s easy to default to the ‘holy trinity’ of Jupiter, Saturn and our neighbour Mars. Each boasts unique and relatively easy to observe features, from Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s bands and Great Red Spot, to Mars’s dusty surface. But why stop there? There are eight planets in our Solar System and many can be appreciated with beginner setups. The ‘inner planets’, Mercury and Venus, present new and exciting challenges to planetary astronomers. We explored Venus in last month’s issue and now it’s Mercury’s turn for the spotlight.

Due to its proximity to the Sun, extra care must be taken to observe Mercury safely, which adds to the challenge. There are particular times that are best to view this elusive, mysterious planet, and this April we can seize the opportunity. Get ready to enjoy one of the Solar System’s unsung heroes.

Following Mercury’s path

The fastest planet in the Solar System, Mercury is named after the messenger of the Greek gods, renowned for speed. And time is certainly of the essence with this planet. To catch Mercury, we need to understand how its position relative to the Sun affects its visibility.

Mercury is 0.4 astronomical units (AU) away from the Sun and orbits at speeds of up to 47km per second, compared to Earth’s relaxed pace of 30km per second. When it reaches its closest point to the Sun, Mercury is at its fastest and it then slows down slightly the further away it gets. As the innermost planet, it also has the shortest year, taking 88 Earth days to circle the Sun.

The gravitational influence of the Sun affects Mercury’s orbit in other ways too. Mercury’s journey around the Sun is highly ‘eccentric’, or egg-shaped: this means the distance between the two can vary from 46,000,000km to 69,000,000km. Moreover, just because Mercury’s years are short, it doesn’t mean its days are. In fact, it rotates so slowly on its axis that it completes one full rotation roughly every 59 Earth days. When we consider the speed that Mercury travels versus its slovenly rotational rate, we realise it doesn’t experience conventional sunrises and sunsets to mark day and night times – one ‘solar day’ (a full day–night cycle) on Mercury is 176 Earth days!

Another thing that makes Mercury unique is its lack of moons. Anything likely to be bound to the planet is instead attracted by the strong pull of its host star.

Elongations and conjunctions

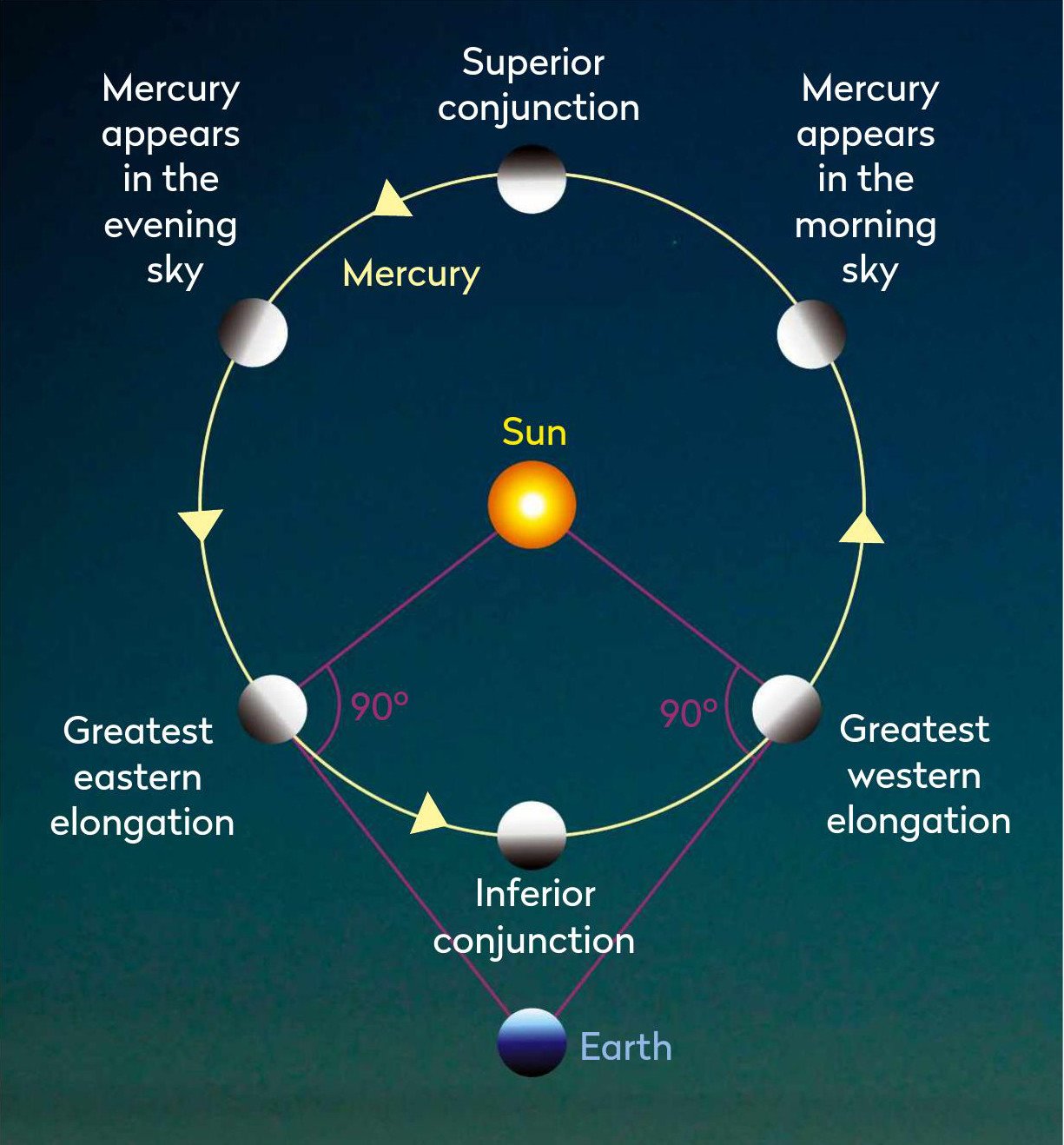

Because Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun, it always appears close by and is often swallowed by our home star’s glare. Mercury’s appearances are therefore closely linked with our sunrise and sunsets, making it a morning or evening object, rather than something we can look for during later hours.

The best time to view Mercury is during greatest elongation, which next occurs on 11 April. This is when Mercury is farthest from the Sun, so it is placed far either to the east or west side of it (known as eastern and western elongations, respectively). What we’ll have on 11 April is a greatest eastern elongation event. This places it a little further from the Sun’s glare and at its highest altitude, helping us to view it. The angular separation due to elongation can vary from roughly 20° to 28°, the equivalent of one handspan to three clenched fists next to each other, held at arm’s length. When positioned at the eastern side of the Sun, Mercury appears in our evening skies; when at the western side it appears in early morning skies. When it makes its evening appearances, the planet is seen above the western horizon shortly after sunset in twilight (as it will be around 2–15 April), and as a morning planet it appears in the east shortly before sunrise (as it will be around 27–31 May). A very clear eastern horizon will be needed.

These elongation events mark Mercury’s best and safest observing periods. Because Mercury is closest to the Sun, elongations are regular and happen every 3–4 months. It’s at this point that the planet will appear highest above the horizon, placing it at the best position to observe as it will be clear of light pollution and least affected by atmospheric seeing. Mercury reaches this point on 11 April, making this a great time to start looking for it. Even so, it never strays far from the Sun, with this elongation only reaching a maximum angular separation of 19.5°.

Inferior and superior conjunctions are specific to the inner planets, and mark times when we can’t view Mercury. Inferior conjunctions refer to times when Mercury or Venus pass directly between Earth and the Sun, positioning them in front of the Sun at sunrise and sunset, so they are lost in its glare. Superior conjunctions refer to times when these two planets are positioned on the opposite side of the Sun to Earth, again making them unviewable. Mercury next reaches inferior conjunction on 1 May and superior conjunction on 1 July.

So what can we observe when the time is right for Mercury? Despite its challenges, the planet can be appreciated with and without a telescope. If viewed with the naked eye, it tends to appear as a bright point object, similar in appearance to a star, with its magnitude varying from as bright as mag. –2.8 to a dim mag. +7, when it is only visible through binoculars or a telescope. If close to the horizon, atmospheric turbulence might make it appear to ‘twinkle’ like a star. However, if you take some time to study it unaided you will detect a subtle, rosy, golden tinge that singles it out from the starry background. Mercury’s apparent diameter, depending on its distance from Earth, can range from 4.5 arcseconds at apogee to 12.9 arcseconds at perigee. A pair of low-powered binoculars will help you locate the planet, particularly at times when it is dimmer.

Because Mercury is often viewed against brighter skies, a telescope will help you locate it. Again, you’ll want clear western or eastern horizons (depending on when you’re viewing). With a 3-inch scope you’ll start to appreciate Mercury’s phases. Although the planet is unobservable at its full phase during superior conjunction and at its new phase at inferior conjunction, even in the short windows of opportunity in between you will notice changes in its phases.

While we won’t see craters, on nights of exceptional seeing and minimal turbulence, we may discern some surface details with larger-aperture telescopes. With all planetary astronomy, seeing conditions will greatly affect observations. Therefore, providing it’s safe to do so, try to catch the planet at its highest possible altitude, at a minimum of one hour outside of sunrise or sunset times.

Because it is so closely bound to our Sun, it is imperative when viewing Mercury to avoid the risk of viewing the Sun directly. Never try to find Mercury in broad daylight or during conjunctions; aim instead for elongation events. Ascertain the sunrise or sunset time on the day of observation and use a sky guide to establish the angular separation of Mercury from the Sun. Ensure that the full disc of the Sun is behind the horizon at the time of viewing.

When to observe Mercury

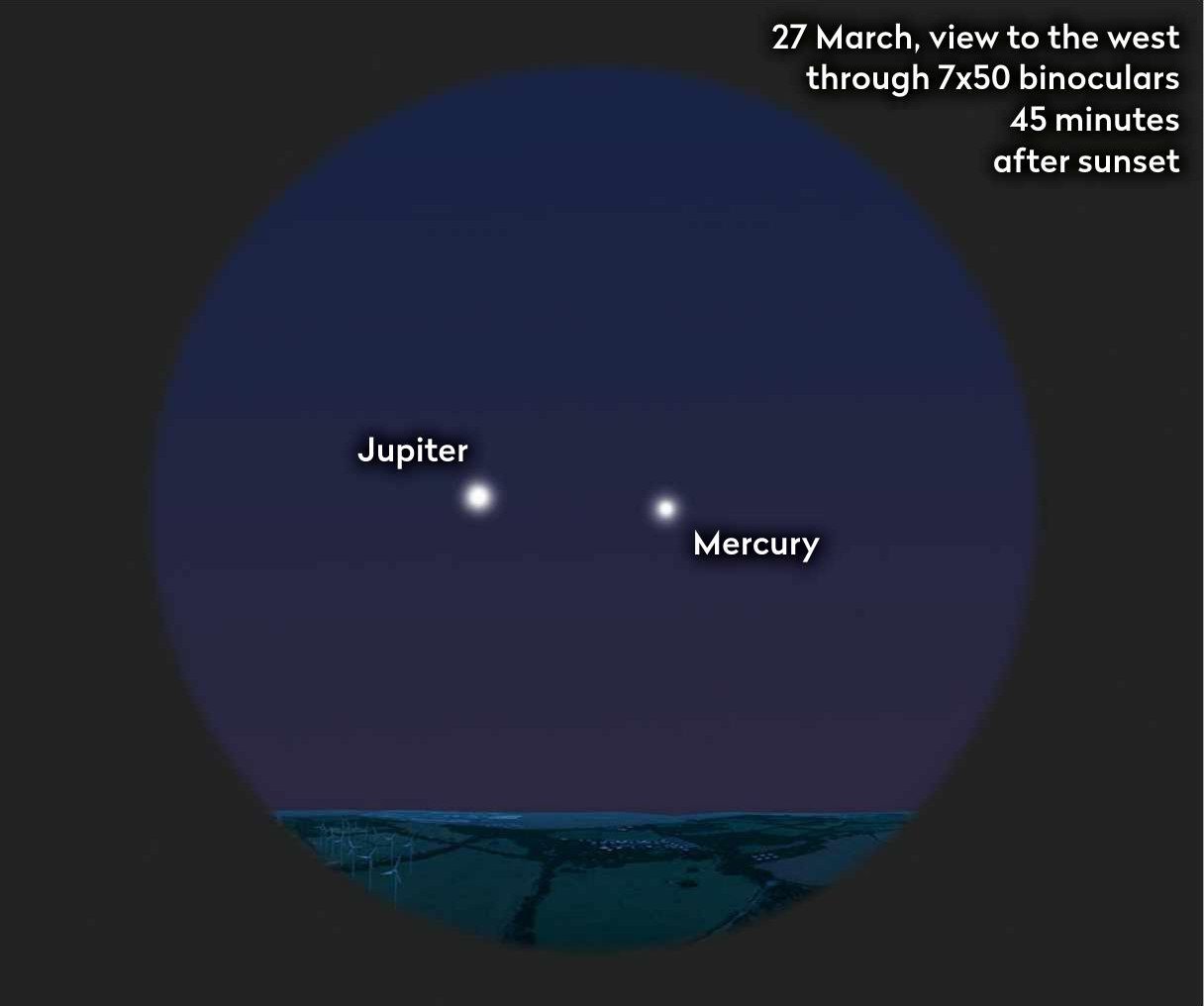

You can catch Mercury in the evening sky and close to Jupiter on 27 March, less than half a degree apart from Jupiter’s southeastern limb. It will be a bright mag. –1.3, comparable to Jupiter at mag. –1.59, and great to view whether with the naked eye or through a telescope. Be quick, however, as it will set an hour after sunset, which is at around 19:25 BST (18:25 UT). A clear western horizon is needed.

April is a great time to view Mercury as it meets all the criteria required to enjoy this planet: it’s at its furthest distance from the Sun and relatively high above the horizon at sunset, meaning we can catch it once the Sun is safely out of the way. Mercury is best at the start and middle of the month, when its magnitude will vary from mag. –1.0 to mag. +1.2 over the first two weeks – very bright to the naked eye, providing you have good horizons. It will be at greatest elongation east on 11 April, reaching 16° altitude and positioned close to both Uranus and Venus at sunset. It will set two hours later, giving us plenty of time to see it. The remainder of April will see Mercury dim as its peak altitude gets lower. By the month’s end, it is expected to be mag. +4.3 and only 6° above the western horizon at sunset.

From the end of March to the end of April, those with telescopes can observe Mercury wane from an almost full 91%-lit disc on 28 March to 7%-lit on 24 April. Naturally, as the disc becomes smaller the planet dims and therefore becomes harder to make out, in addition to sinking further towards the horizon.

Whether you’re looking with the naked eye or using magnification, if you’ve never taken the time to appreciate Mercury before, now’s the perfect time.

What’s next for Mercury?

Keep an eye out for more chances to see the planet in the months ahead

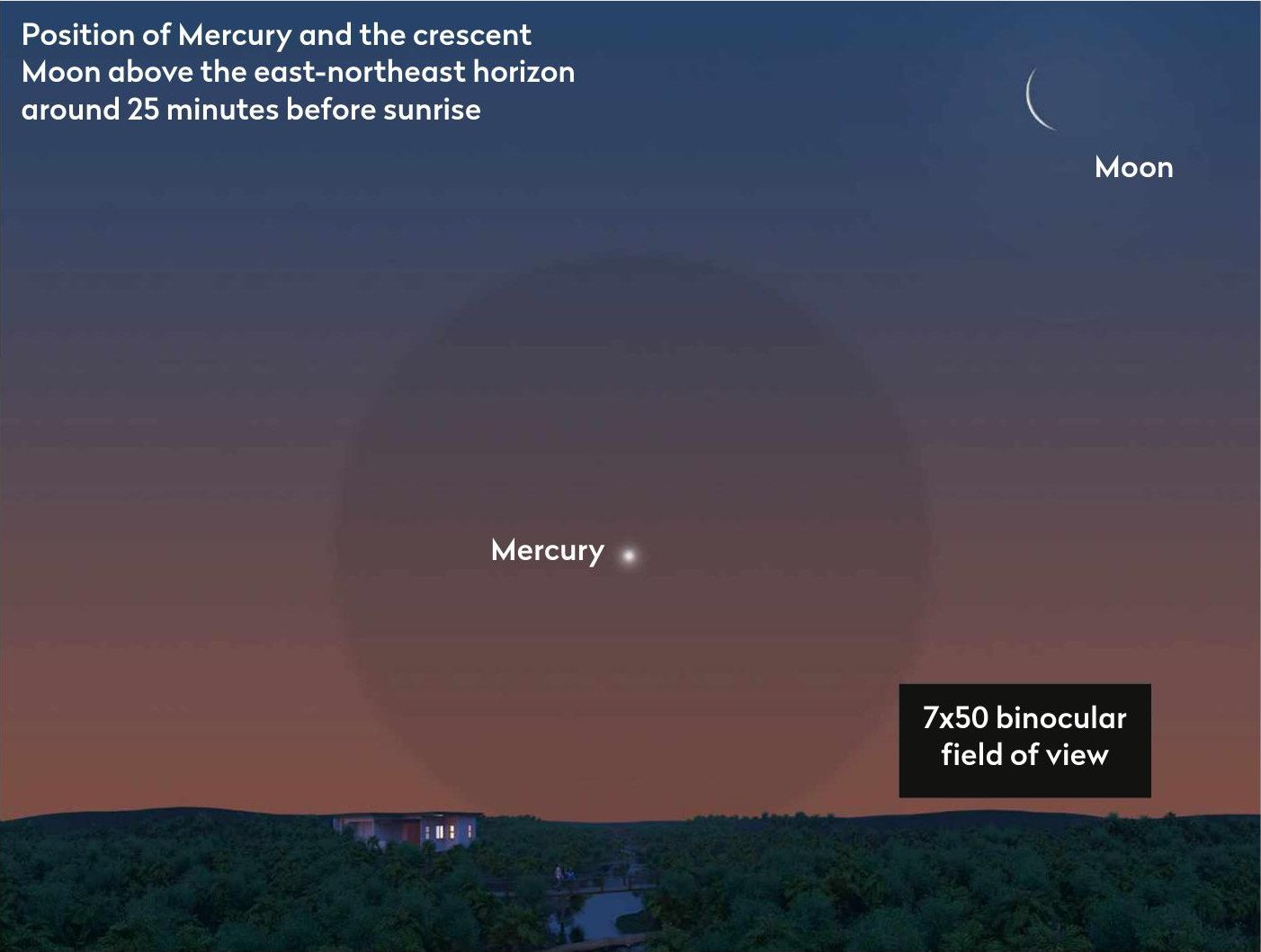

After April, Mercury goes quiet for a little while. On 1 May there’s an inferior conjunction, where it’s positioned directly between the Sun and Earth. This position in the morning sky will make it almost impossible to observe as not only is it hidden in the Sun’s glare, but it appears as a thin crescent so is hard to pick out even with a telescope. On 29 May it will reach greatest western elongation. On 16 June, it will appear close to a 3%-illuminated Moon. July and August will prove disappointing for Mercury, as at best it will make brief appearances very low on the horizon and in light evening skies.

September will see Mercury’s greatest western elongation on 22 September, meaning the planet will make another welcome appearance, rising 100 minutes before sunrise and climbing to 10° above the eastern horizon. Make the most of the planet looking bright in early morning skies during the first week of October before it lurks low on the horizon after sunset for much of November. By 31 December, Mercury will make a final brief appearance in the morning, just above the southeast horizon before sunrise.

Unravelling Mercury’s mysteries

What do we know about the innermost planet, and how has humanity explored it?

Mercury is the smallest planet, barely larger than our own Moon at a mere 2,440km in diameter. As it’s also the closest to the Sun, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s the hottest planet in the system, but that’s not the case due to a thin ‘exosphere’ of oxygen, hydrogen, sodium, helium and potassium. Lack of heat retention means its surface temperature varies from almost 450°C in the day to –180°C at night. Despite being further away, Venus reaches temperatures up to 470°C thanks to its thick atmosphere.

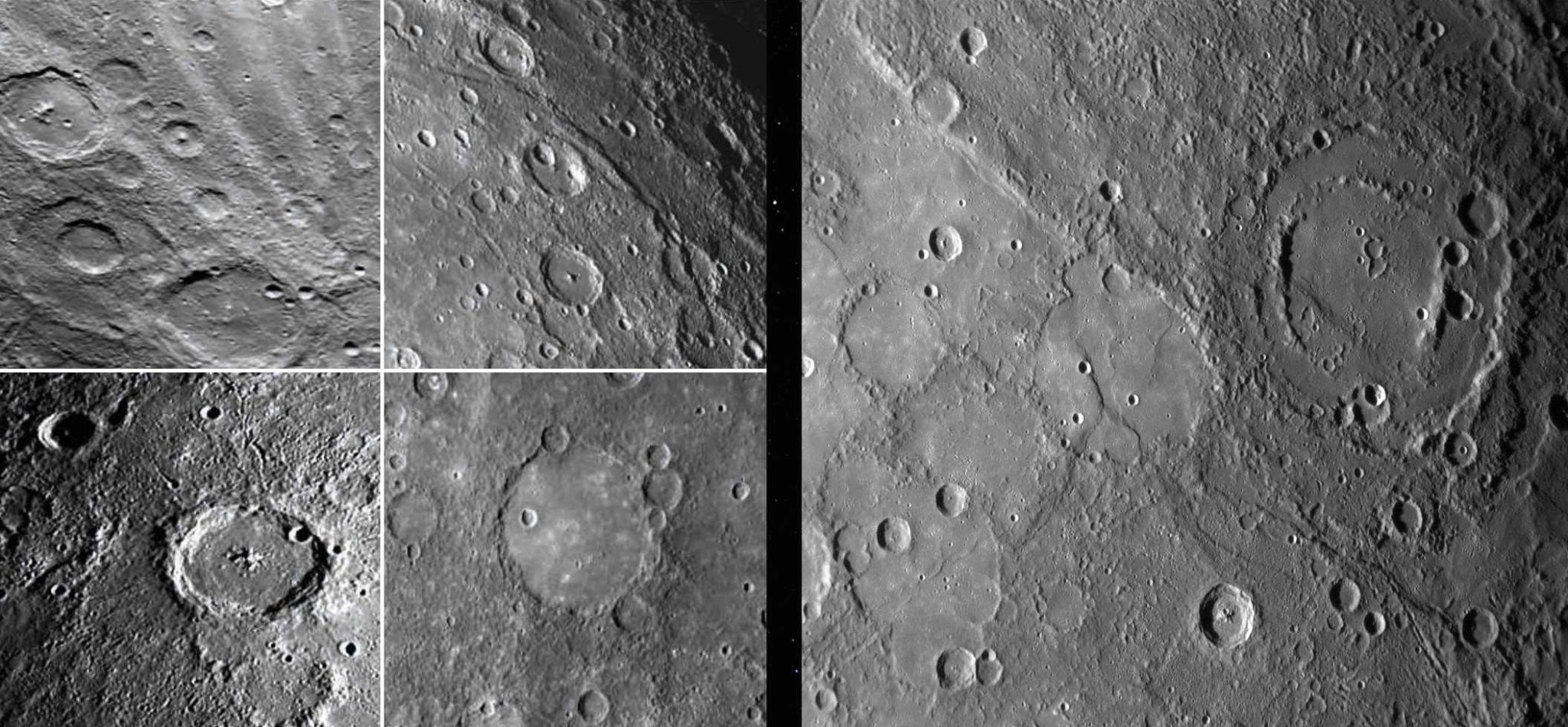

Mercury is a ‘terrestrial’ or rocky planet, displaying a cratered surface that resembles Earth’s Moon. Underneath lies a large metallic core, mantle and crust. Thanks to a minor axial tilt (2°), Mercury doesn’t experience seasons.

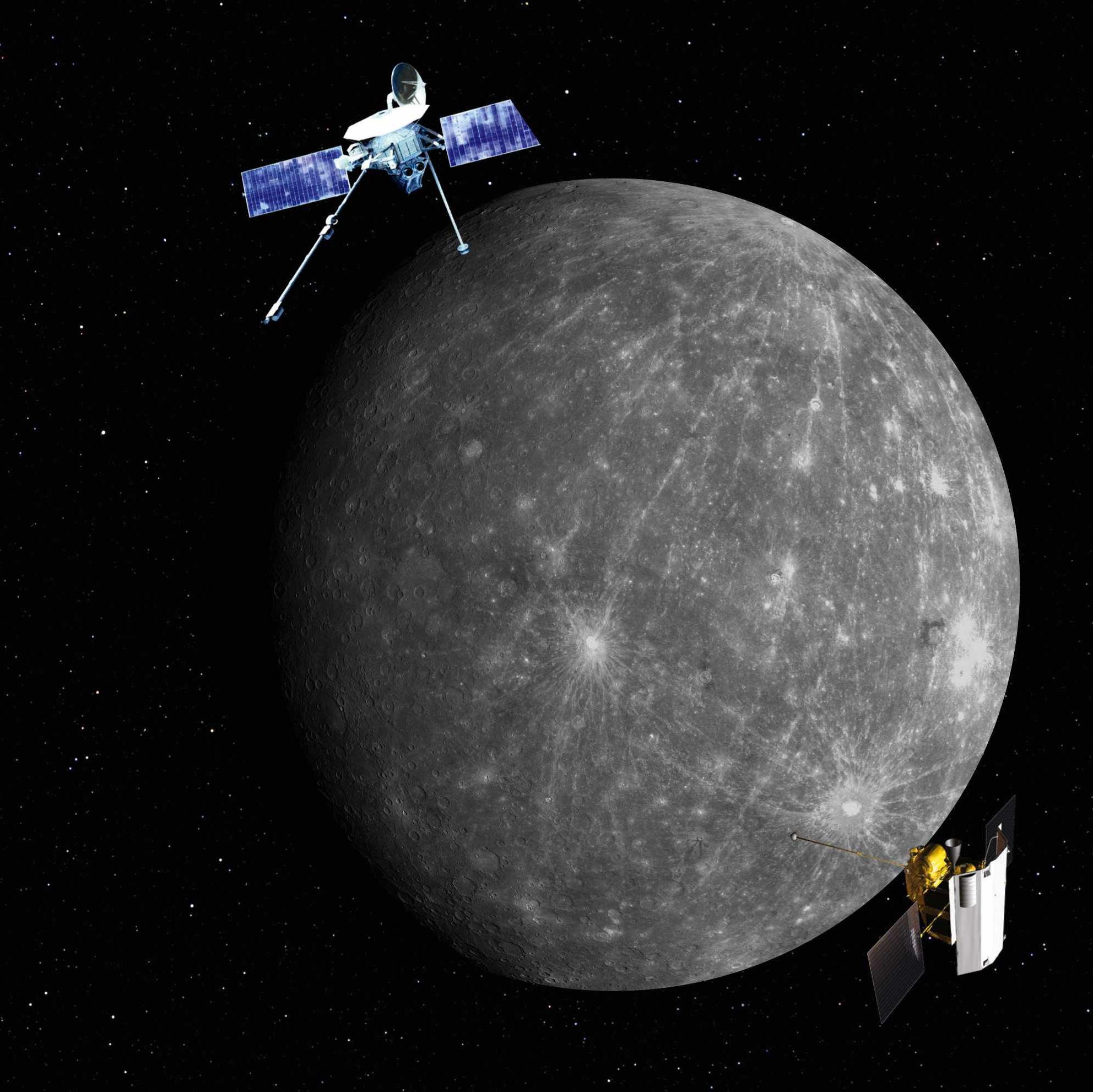

To date, two NASA missions have visited Mercury. Mariner 10 launched in 1973 and flew past the next year, observing the cratered surface. Messenger followed in 2004 and was the first to orbit, in 2011. Discoveries included ice at the poles and the presence of relatively new fault ‘cliffs’ on the surface, hinting at tectonic activity. These fault lines suggest Mercury is contracting and ‘shrinking’ as the molten interior cools, warping the surface. Over its lifetime, Mercury is estimated to have shrunk by almost 16km (10 miles).

The European Space Agency now has BepiColombo winging its way over, expecting to arrive in 2025. It will take a closer look at the magnetic field, core and polar ice, to learn more about Mercury’s early life.

For more details about observing Mercury this month, take a look at the planets section in our Sky Guide.

Charlotte Daniels is an experienced practical astronomer and astrophotographer