COSMOLOGY CRASH COURSE

Does the Universe have an edge?

Part 4 of our series in which Govert Schilling explains cosmology’s most complex concepts

It’s one of the most perplexing questions in cosmology: does our Universe have an edge? If you keep travelling in an imaginary faster-than-light spaceship, would you ever arrive at some boundary, unable to go any further? And if so, what lies beyond? It’s all very hard to imagine. Then again, an infinite Universe is just as difficult to wrap your head around. After all, there must be something that space is expanding into, right?

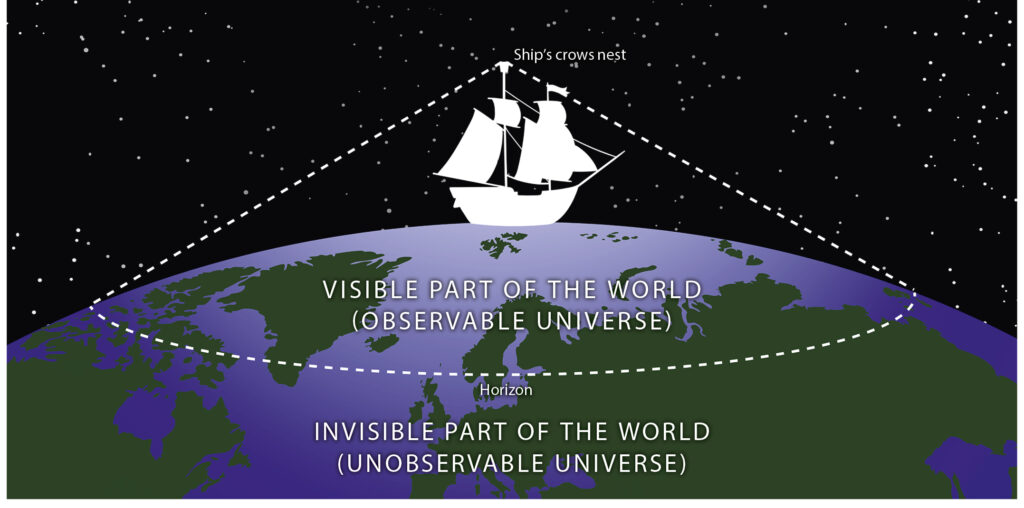

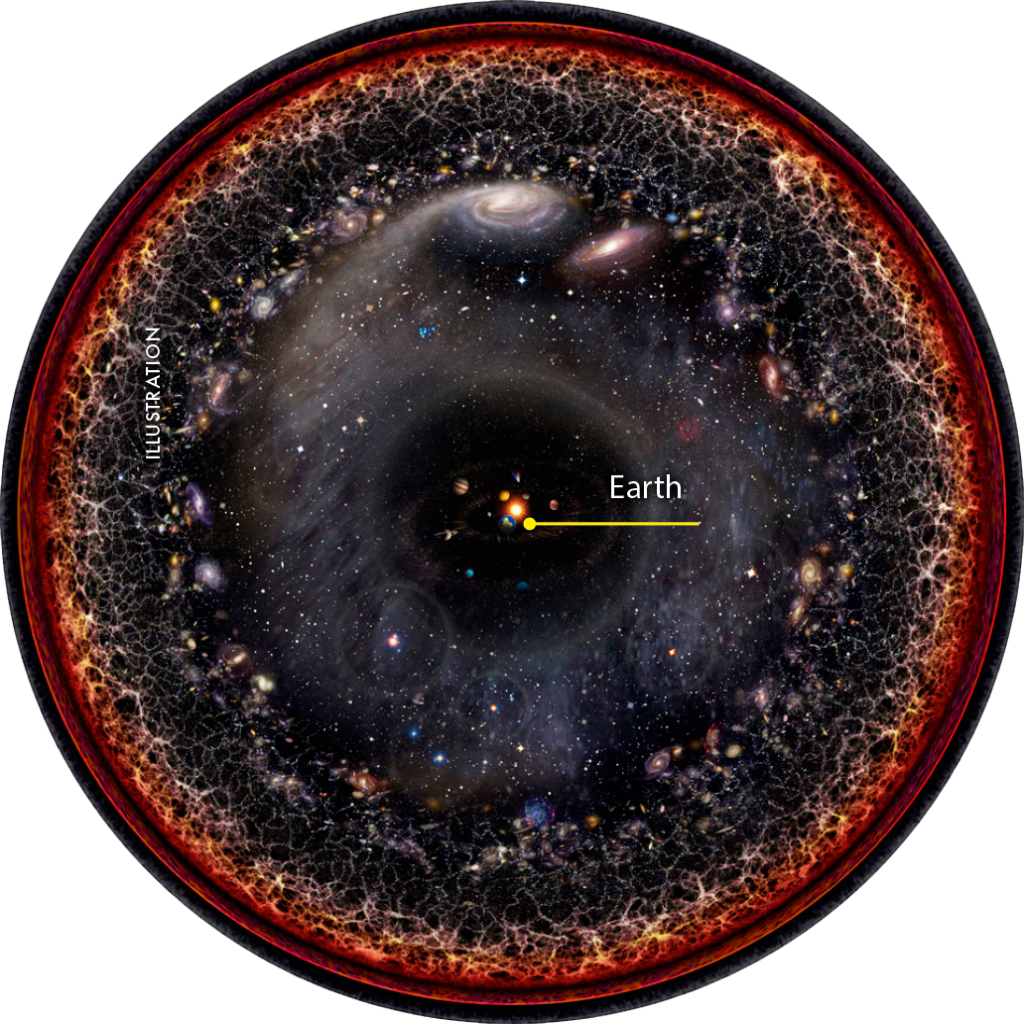

Let’s start with a related but easier-to-grasp concept: our Universe has an apparent edge, called the cosmological horizon. The light emitted right after the Big Bang has been travelling for 13.8 billion years through space. This means we can only see the Universe up to a current distance corresponding to a light-travel time of 13.8 billion years. Thanks to the expansion of space, this so-called co-moving distance is approximately 45 billion lightyears, and anything beyond this limit is unobservable to us because not enough time has elapsed since the birth of the Universe for light from these remote regions to reach our telescopes.

But, just like the familiar horizon seen by sailors on the ocean, this cosmological horizon is not some real, physical boundary. And as the ocean stretches beyond the sailor’s horizon, so too does space stretch beyond our observable Universe. There’s no reason why there can’t be galaxies at these extremely large distances; they’re just invisible to us, no matter how powerful our telescopes are.

But knowing the Universe goes on beyond 45 billion lightyears still doesn’t tell us whether it’s finite or infinite. But one thing’s for sure: the Universe does not have an edge. There’s no physical boundary – no wall, no border, no fence around the edges of the cosmos.

Curve appeal

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the Universe is infinitely large though. In principle, we could live in a finite Universe, provided that three-dimensional empty space is geometrically curved in a particular way – a distinct possibility according to Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

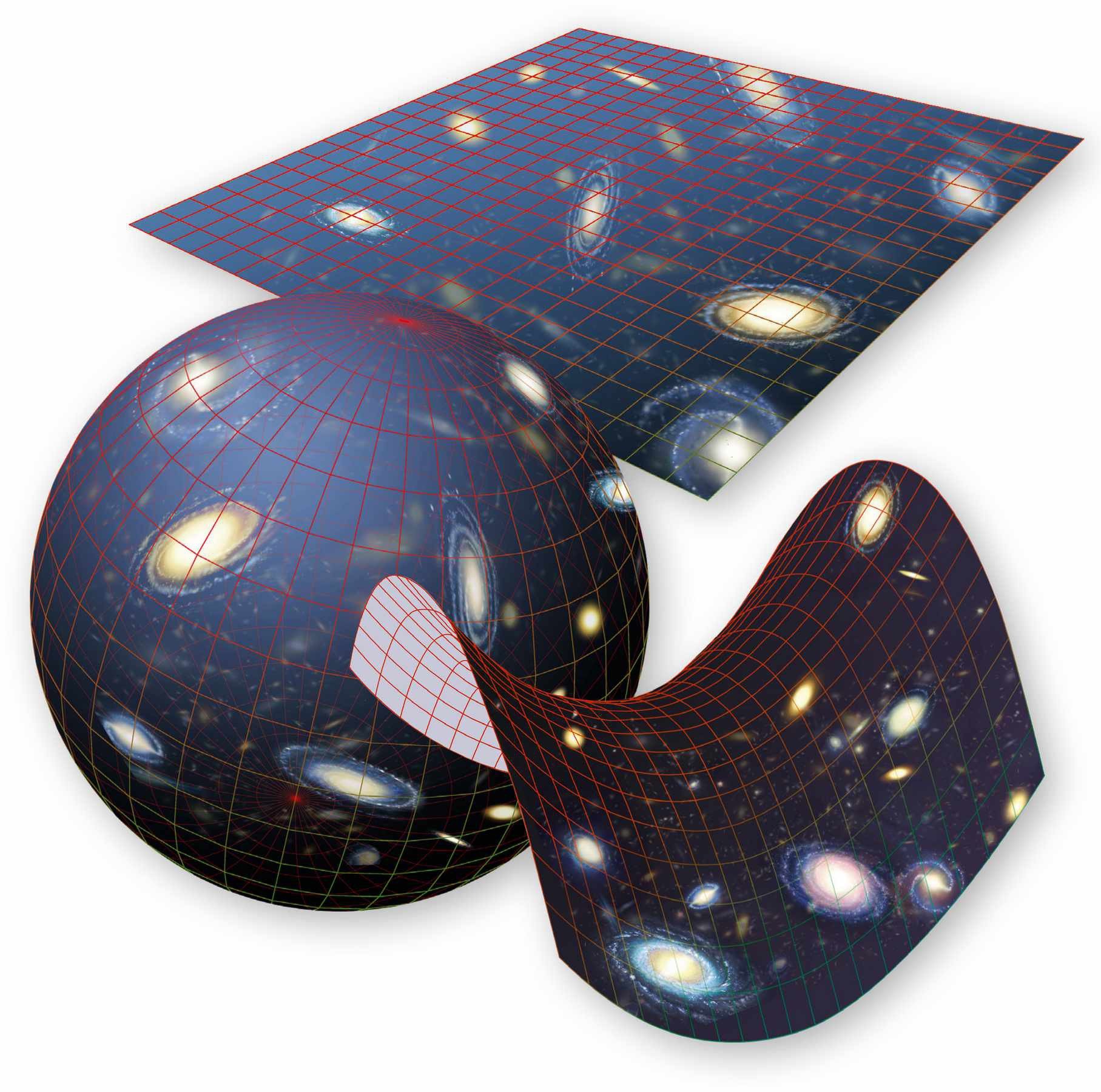

If the Universe has what’s known as positive curvature, it would be like the curved surface of a beach ball, but rather than a 2D surface, it’s 3D space. It is finite – if you were living in this flattened version of the cosmos, you wouldn’t need an infinite amount of paint to cover your 2D Universe – yet there is no boundary or edge to the surface itself.

In contrast, a negatively curved Universe would be a higher-dimensional version of a Pringle – curving upwards along one axis and downwards along the other – while a flat Universe would resemble a piece of paper. Both of these versions would stretch out infinitely.

Cosmologists have tried to measure the largescale curvature of space over the past few decades, and the most recent results combined with theoretical arguments seem to indicate that we live in a geometrically flat Universe. On the one hand, that’s convenient as our brains aren’t very good at imagining large-scale space curvature – even here we’ve had to describe our 3D Universe in 2D terms. On the other hand, this means that our Universe is infinitely large, and that our observable Universe – the part within our cosmological horizon – is only an infinitesimally small fraction of an unimaginably large whole.

In case you were wondering how our infinite, boundless Universe is able to expand, return once again to our 2D analogy. If you saw the grid size on a piece of graph paper growing, you would justifiably conclude that the paper is expanding. If the paper was so large that you couldn’t see the edge, you’d still draw the same conclusion, even though the piece of paper could also be infinitely large. The same is true for an infinite Universe. After all, infinity times two is still infinity!

Once infinite, always infinite

Whether tiny, hot nugget or unimaginably huge cosmos, space goes on forever

In many popular astronomy books, you may read that our Universe was as small as a grapefruit right after the Big Bang. Or you may be told that the Universe began as an infinitesimal, dimensionless point. In fact, the truth is much weirder. Yes, right after the Universe came into existence, some 13.8 billion years ago, space was incredibly more ‘compact’ than it is now, and both the temperature and the matter density of the Universe were incredibly high.

But if our present Universe is infinitely large, it must always have been infinitely large, even at the primordial epoch when all spatial distances were, say, one billion times as small as they are now. After all, infinity divided by one billion is still infinity. What you can say is that our observable Universe – the 45-million-lightyear radius sphere that we can study at present – was once compressed into an incredibly tiny volume. But even back then, an infinite Universe just would’ve gone on forever beyond the ‘edge’ of this imaginary grapefruit.

Govert Schilling’s book The Elephant in the Universe is published by Harvard University Press.