With 70 nations, space-mad billionaires and eager private companies all vying for a stake – but no laws or rules – space today is verging on a free-for-all. Shaoni Bhattacharya hears discussions on the challenges at the Abu Dhabi Space Debate

Last summer, Ian Christensen was staring up at the night sky above a US National Park and International Dark Sky area. He and his companions were listening to a ranger talk about the wonders of the night sky when they were confronted with an unexpected sight: a train of dots crossing the Milky Way.

“For me it was a crystallisation,” he told delegates at the Abu Dhabi Space Debate. “Here’s a system with benefits… but also a direct and discernible impact on how we as a species engage with the environment.”

Christensen – who is the director of private sector programmes at the Secure World Foundation, an organisation that aims to promote space sustainability – was one of many speakers at the two-day meeting in December 2022, organised by the United Arab Emirates. It was the first-ever international meeting solely dedicated to addressing new space challenges on a global scale. While space has been on the agenda at major world meetings before, including the COP climate meetings, it has always been as an adjunct, a side issue among many others.

Now with rising numbers of new players in space, out-of-date rules and tensions rising both on Earth and in space, the Space Debate aimed to provide a forum to cooperatively discuss the future of space. Safety and the sustainability of space were high on the agenda. Who owns space? Who makes the laws? Who will pay for the clean-up of space debris? These were some of the questions running through the debate.

“We have moved from the bi-polar world of the Cold War and its Space Race to a multilateral world where some 70 nations are space-capable; where a fast-growing private sector is taking an increasing role and global tensions have threatened some of the most cherished aspects of our exploration of space,” said Her Excellency Sarah Al Amiri, chair of the UAE Space Agency in her opening remarks.

A problem shared

The ‘new Space Age’ has brought with it many issues, Al Amiri highlighted, including the growing problem of space debris and of our most important piece of existing international legislation, the Outer Space Treaty, being more than 50 years out of date.

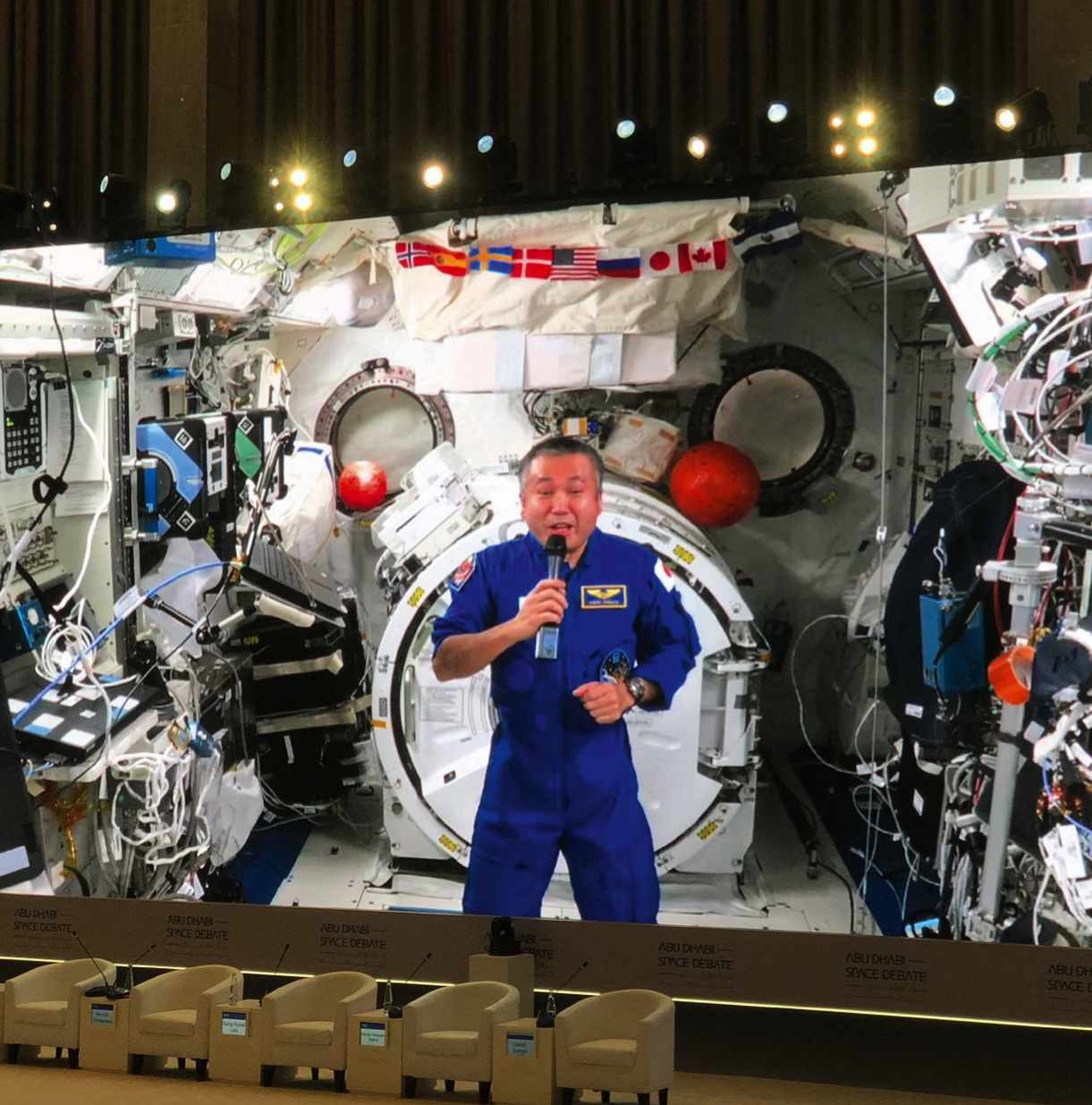

The meeting was attended by world leaders, representatives from space agencies and private companies. At one point, Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata provided some pazazz to proceedings by speaking online from the International Space Station to delighted delegates, flying upwards in microgravity at the end of his address to whizz off screen.

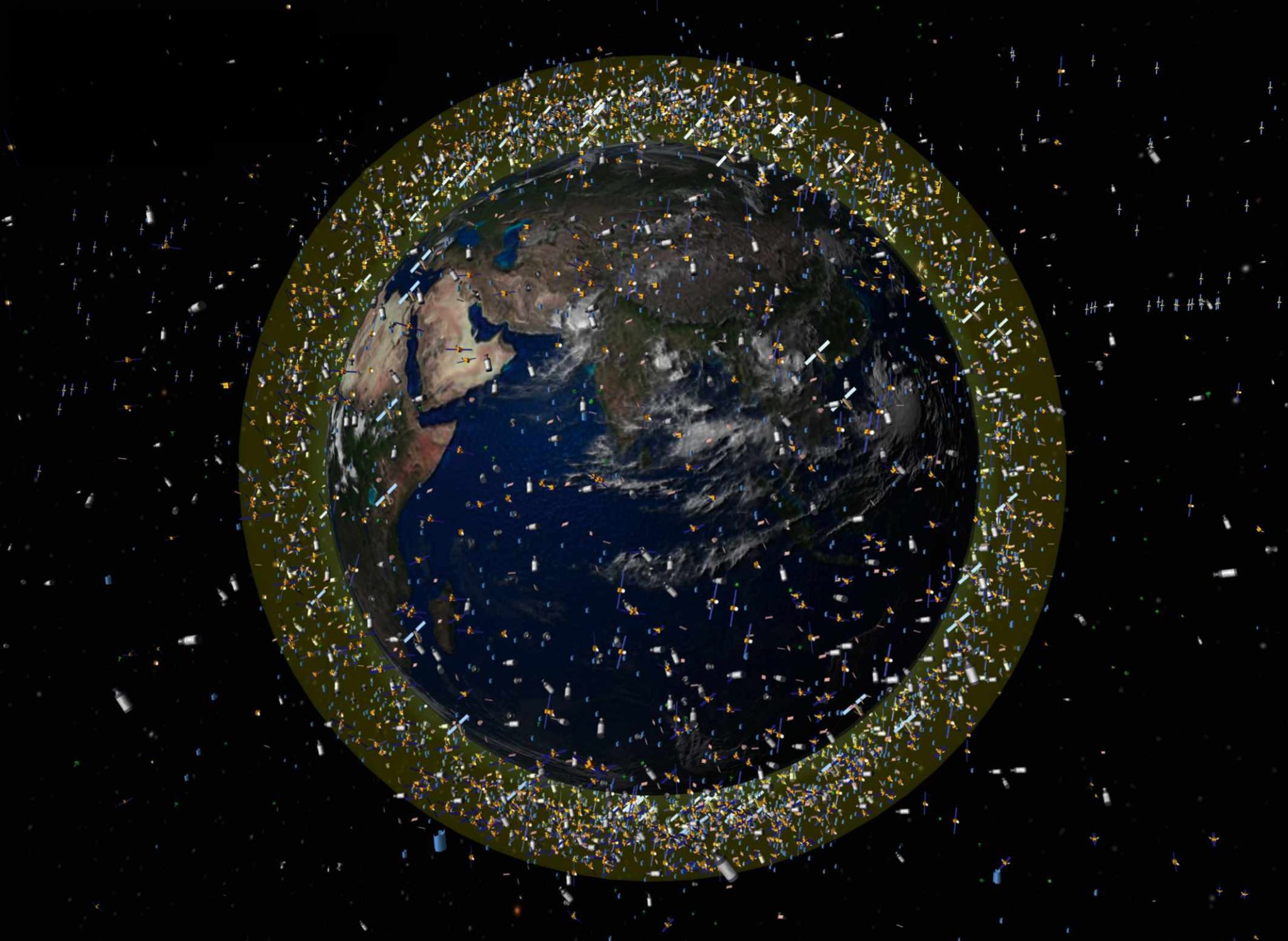

With access to space becoming easier and cheaper, there are huge opportunities to be had, such as improving broadband accessibility in underserved communities and providing Earth observation capabilities to help combat climate change. But there are also concerns. One major worry is that space is becoming increasingly congested, especially in low-Earth orbit (LEO). In recent years, this has been compounded by the rise of giant networks of thousands of satellites called megaconstellations. Of the 6,000 satellites in orbit, half are part of the Starlink network, and another 9,000 are planned. There are even some reports that the company has requested authorisation to launch up to 42,000. The number is only set to grow as other private space companies around the world prepare to launch their own constellations over the next few years. It’s becoming increasingly clear that LEO is a finite resource.

“While some may look at the possibility of endless exploitation as perhaps our ancestors looked at the oceans, we know that there are limits,” said Adnan Al Muhairi, chief technology officer of satellite company Yahsat. “We have over 250 new companies that have made announcements for constellations. Some are looking at tens of thousands [of satellites]. Not to mention the potential entry of over 100 new launch vehicle manufacturers as well.”

Growing anxiety about satellites

Mega-constellations impact our ability to view the cosmos around us

Human activity in low-Earth orbit is rapidly increasing. There were about 800 active satellites in LEO in 2019, according to Dan Ceperley, CEO of LeoLabs. There were about 6,000 satellites in LEO at the time of the meeting in December, but this is on track to rise to 10,000 satellites by the end of 2023.

As well as safety and sustainability issues, the number of satellites has raised concerns for astronomers and stargazers. “As these systems have been deployed, we’ve found that they actually optically interfere with telescope observations,” said Ian Christensen of the Secure World Foundation. “They’re deployed in ‘trains’ – 50 or 60 in a single launch – and as those satellites transit across the field of view of terrestrial telescopes, they reflect light back into the telescope and interfere with the ability to collect clean observations.”

Christensen did highlight there has been constructive dialogue between the optical astronomy and satellite-operating communities. The International Astronomical Union has established a Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Skies, with four working groups focusing on different issues, including working with industry to design practices for satellite constellations that might reduce the amount of interference and contamination of images.

Hopefully, these measures would also reduce the visibility of these systems to the general public too, protecting it not just for stargazers, but the many cultures and religions around the world that have a deep connection to the night sky.

Debris dilemma

With so many new entrants, safety and sustainability are a concern to both public and private sectors. The increasing use of LEO has implications for radio astronomy and stargazing due to the light pollution caused by these satellites, but they are also a threat to humanity’s continued use of space and the many advantages that it brings, due to increased space junk. A fragment of a spacecraft as small as 3cm could cause catastrophic damage to another spacecraft should they strike each other, and there are already thousands of pieces of debris.

Meanwhile, the private sector is well aware that sustainability in space is integral to its business. “For us to survive as companies, we have to create a sustainable space future,” said Erika Wagner from spaceflight company Blue Origin.

“It’s on our shoulders to make sure this is safely operated, safely regulated,” says Laith Hamad, from communications company OneWeb. “If you have one collision – only one collision – and you start the Kessler effect, then space is of no use to us.”

“Technology in and of itself is not going to solve the problem if we don’t have a radical rethink about how we approach space” – Steven Freeland

The Kessler effect or Kessler syndrome is a situation theorised by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978 where the density of satellites, spent rockets and other space junk becomes so high that it reaches a critical mass and just one collision could trigger a runaway cascade. Each collision creates more debris, which increases the chances of a collision, creating even more debris and so on, until orbit becomes unusable.

Hooked on space

Many made comparisons between humanity’s unsustainable use of Earth and what our species is currently doing in space. Carrying on with a ‘business as usual approach’ could run a real risk of space becoming unsustainable, warned Steven Freeland, vice-chair of a UN working group on Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activities.

“We are all dependent on space for all aspects of our lives – it’s part of the critical infrastructure,” said Freeland. “It could put us all back into the Dark Ages.”

If LEO does veer into such a path, the results could be irreversible. While technology such as using lasers or nets to actively remove space debris, or space tracking might offer potential solutions, it isn’t enough.

“Technology in and of itself is not going to solve the problem if we don’t have a radical rethink about how we approach space,” said Freeland.

Interestingly, he pointed out that while the whole world would suffer if space became unusable, it would be the richer, more powerful countries that would suffer the most – a stark contrast to the situation with climate change on Earth. This is because the largest spacefaring nations are also the most dependent on the incredible advantages space offers, and therefore the most vulnerable. This common interest would be a powerful tool to promote changes to the way the world adapts to and uses space.

One of the biggest problems, however, is that space is shared between all humanity. There is currently no universal set of rules or agreements that cover all spacefaring nations and the private sector. Nor is there an overarching regulatory or enforcement body, as noted during the debate, making space potentially a free-for-all. The Outer Space Treaty provides some basis for global space cooperation. More recently, 21 countries signed up to the US-led Artemis Accords. But neither one covers the private sector.

“Do we need a commercial version of these Accords?” asked Mike Gold from aerospace manufacturer Redwire Space, who previously led the development of the Accords while at NASA. He said the Outer Space Treaty provides the “fundamental bones of space law” and would be a “wonderful foundation to build upon” for more present challenges.

Uneasy alliances

Many at the Space Debate raised concerns about how tensions on Earth – the war between Russia and Ukraine, for example – would affect cooperation and dialogue around space. Could such a grand treaty be reached by many, many nations in the current geopolitical climate?

Gold noted that it is possible for countries to cooperate, giving the example of the International Telecommunications Union, which globally coordinates frequency resources for satellite licences obtained by national authorities. “There were countries at war with each other and they still came together for the ITU,” he said.

While many challenges were debated at the Abu Dhabi meeting, no agreements were reached other than the general acceptance of the need for discussion and cooperation. “We don’t have the answers – but we needed to start the discussion somewhere,” said His Excellency Omran Sharaf, chair of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

While the Outer Space Treaty has played a role in maintaining peace, Sharaf emphasised the importance of keeping pace with evolving technology.

“We cannot just rely on the old systems and expect that it’s going to work for now or for the future,” says Sharaf. “And we need to be very progressive in looking into these systems that will not just address the problem today but will address the problem 50, 70, 100 years down the line.”

The law in space

Rules governing space – such as they are – are decades out of date

There is no set of rules or laws that encompasses all the new players in space, be they governments, space agencies or the commercial sector. However, many in the space industry say that the UN’s 1967 set of rules, the Outer Space Treaty, provides a good basis upon which to build. Originally signed by the USA, Russia and the UK, it primarily ensures the peaceful use of space.

By signing it, those nations have pledged to abide by several key tenets: not to place weapons of mass destruction including nuclear ones in Earth orbit, the Moon or elsewhere in space; to provide assistance to all astronauts in distress; and that the states will be liable for any damage caused by their space objects.

One of the most recent attempts at a new agreement built upon the Treaty are the Artemis Accords, launched in 2020. The Accords aim to promote peaceful and cooperative exploration of the lunar surface, and were led by NASA ahead of its plans to extensively explore the Moon over the coming decade. To date, 23 nations have signed, but notably absent are Russia and China. The Accords contain sections governing rights to resource extraction, which Chinese space commentator Song Zhongping described as “in pursuit of colonisation and claiming sovereignty over the Moon,” proving just how difficult coming to an agreement could be.

In addition, these agreements are aimed at governments and state players, and it’s not clear exactly how they would govern the private companies leading the booming space industry.

Shaoni Bhattacharya is a science writer, editor and short-fiction author