Ezzy Pearson reveals how Valentina Tereshkova and Sally Ride blazed the trail for womankind

Sixty years ago this June, a Soviet factory worker with a passion for parachuting became the first woman to fly in space. Twenty years and two days later, half a world away a tennis-playing astrophysicist followed suit to become the first American woman in space. This month, we take a look back at the flights of Valentina Tereshkova and Sally Ride – two individuals who forged the way for women in space. Yet while one’s flight remained something of a one-off with little lasting effect on her nation’s space programme, the other’s was the start of a step-change in outlook that continues to this day.

Born on 6 March 1937, Valentina Tereshkova was the daughter of a tractor driver who died during World War II. Upon reaching adulthood, Tereshkova worked in a textile factory, continuing to study in her spare time. Unlike most future astronauts, she did not spend her childhood dreaming of space. Instead, it was a different passion that decided her path – parachuting. She began the hobby in 1959 after seeing an advertisement for a local club, and by the early ’60s she was jumping competitively.

At the time, the Soviet Union dominated the Space Race. It had successfully put the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into space, but there were concerns that the US might launch a female astronaut just so that they could claim that ‘first’.

“We cannot allow that the first woman in space will be American,” Nikolai Kamanin, director of cosmonaut training, wrote in his diary, and soon began seeking out potential candidates.

Previous cosmonauts had been drawn from the air force, but with no female pilots, Kamanin instead looked for experienced parachutists. They would need to be under 30, as well as under 5 foot 7 inches (1.7m) in order to fit into the single-person Vostok crew capsules. Tereshkova was one of five women who fitted the criteria and underwent cosmonaut training. During this, the women were put through tests to ensure their bodies could cope with the physical demands of spaceflight, were taught to fly MiG jets and instructed on the workings of their spacecraft.

Soviets surge ahead

Once training was complete, the question became which of the five women would fly. As it had been with Gagarin before her, it was Tereshkova’s origin story that gained her her seat on Vostok 6. She was the embodiment of the Communist ideal: the daughter of a farmer who had died for his nation, who had educated herself, proving anyone – man or woman – could rise through hard graft. It was for this that Kamanin referred to Tereshkova as “Gagarin in a skirt”.

Her flight launched on 16 June 1963 with the exuberant yell of “Hey sky, take off your hat. I’m on my way!”.

Part of her mission was to look out of the window and take photos of the atmosphere, which would be used to study particles in the upper stratosphere.

“I see the horizon,” she said looking out from the cockpit. “A light blue, a beautiful band. This is the Earth. How beautiful it is! All goes well.”

Despite her upbeat words, the cramped Vostok capsule meant Tereshkova was uncomfortable for most of the flight. A combination of zero gravity and unpalatable food meant she often felt ill. Then, after she vomited she found out that the ground crew had forgotten to include toothpaste with the toothbrush they’d packed for her.

Despite this, Tereshkova handled the craft well. On her first orbit, she passed within five kilometres of Vostok 5, which had launched just two days before her, the manoeuvre testing several procedures that would allow future spacecraft to dock together. She returned to Earth three days and 48 orbits later, narrowly avoiding disaster when she noticed that the Vostok’s guidance programme was set to ascend from orbit, rather than descend. As with all Vostok missions, she ejected before impact and parachuted to the ground, ending her space journey using the very skill that had got her there.

In the weeks and months that followed, Tereshkova became a celebrity, with several parades in her honour. Behind the scenes, though, there was a very different sentiment. While there had been plans for the other female cosmonauts to fly, the nation’s lead spacecraft designer Sergei Korolev put a stop to them, citing the fact that one of the candidates already had a family.

“They forbade me from flying, despite all my protests and arguments,” Tereshkova said years later. “After being once in space, I was keen to go back there. But it didn’t happen.”

Though the female cosmonauts disagreed with the decision, and wrote to the central party committee, their opinions were ignored. The Soviets had claimed their ‘first’.

Cosmonaut women

Tereshkova got there first, but few Russian women followed in her footsteps

After the flight, Tereshkova’s career became centred around touring the globe, and she was the most frequently requested cosmonaut of the entire Soviet spaceflight programme. However, her success meant she never flew again. When Gagarin died in 1968 in a plane crash, the Soviet Union realised it couldn’t risk losing another celebrity, and she was grounded.

In 1963, she married fellow astronaut Andriyan Nikolayev. Their daughter, Elena, was the subject of much curiosity, as she was the first person born to two people who had been in space. They divorced in 1982.

By the time NASA advertised for the 1978 astronaut class, the first intake to include women, the Soviets had yet to put another woman in space. Not wanting to be outdone again after Apollo’s triumph, the next class of cosmonauts included nine women along with four men. Tereshkova herself was allowed to requalify as a cosmonaut. In August 1982, fellow class member Svetlana Savitskaya travelled to the Salyut 7 space station, just beating Sally Ride to be the second woman in space. However, she was the only woman from the class to fly in space and, to date, in total only five of Russia’s cosmonauts have been women.

Politically active throughout her life, Tereshkova has held many offices since retiring from spaceflight and currently sits in the Russian parliament, the Duma.

Meanwhile in America…

NASA could well have beaten them to the punch, however. In 1959, William Randolph Lovelace, the physician in charge of determining who was physically suited to spaceflight, had been curious about how the female body would respond to his tests. He’d secretly called in several women, 13 of whom passed the first stages. He went public with the results, hoping to garner support for further tests, which would require access to military facilities. Instead, many at NASA, including several of the male astronauts, pushed back against the idea. Rather than ban women outright, NASA insisted that candidates needed jet pilot experience which could only be gained in the military – and which did ban women from flying.

The tacit ban would remain in place until 1977, when NASA was selecting its first astronaut class in eight years. Apollo was long over and the agency was looking to crew its new project, the Space Shuttle. With a capacity of eight people, the programme would require many new astronauts. Equal rights for women and for people of colour had become far more prominent in the West since the last astronaut intake, and so the requirements were broadened to accommodate a more diverse range of people.

To push the applicant call to as many people as possible, NASA advertised on TV, radio and in newspapers. It was reading the latter that brought the initiative to the attention of PhD student Sally Ride. A highly active person, Ride had found her first love in the world of tennis. Her prowess at the sport netted her several scholarships to study physics at university and, despite training for hours every day, she excelled academically. She eventually went to Stanford University for her PhD. It was when she was about to graduate and wondering what direction to take her life that Ride spotted the advert.

“The moment I saw that, I knew that that’s what I wanted to do… I wanted to apply to the astronaut corps and see whether NASA would take me and see whether I could have the opportunity to go on that adventure,” Ride said in a 2006 interview at the US Astronaut Hall of Fame.

The USA plays catch-up

In all, 8,079 people applied and just 35 were chosen. Among them were one Asian-American man, three African-American men and six women, one of whom was Ride. After completing basic training in 1978, Ride worked within NASA on the Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System, Canadarm, as well as acting as CapCom on two missions, being the link between ground control and the astronauts in orbit.

The first six crewed flights of the Shuttle were flown with smaller crews from earlier astronaut classes, but by the seventh flight, STS-7, it was time for the class of 1978 to take their seats, and one of them would be a woman. The mission would require Canadarm, with which Ride was well-experienced, but it was Ride’s ability to get along with and work alongside almost anyone that led to her being selected to be the first American woman in space.

NASA had seen the impact being ‘the first’ could have on an astronaut’s life with Neil Armstrong, so officials asked if Ride was willing to accept that fame. She agreed, but in truth Ride had little comprehension of how intense the attention would be. While Tereshkova had been somewhat protected by the Soviet Union’s policy of not publicising missions until they were under way, Ride was under the microscope from the moment her assignment was announced.

“Really the only bad moments in our training involved the press,” Ride said in an interview with feminist Gloria Steinem. “Whereas NASA appeared to be very enlightened about flying women astronauts, the press didn’t appear to be. Without a doubt, I think the worst question that I’ve gotten was whether I cried when we got malfunctions in the simulator.”

She endured the questions and on 18 June 1983 the first American woman headed to space on board the Challenger Space Shuttle.

“The view of Earth is absolutely spectacular, and the feeling of looking back and seeing your planet as a planet is just an amazing feeling,” said Ride in the 2006 interview. “It’s a totally different perspective, and it makes you appreciate, actually, how fragile our existence is.”

A flair for spaceflight

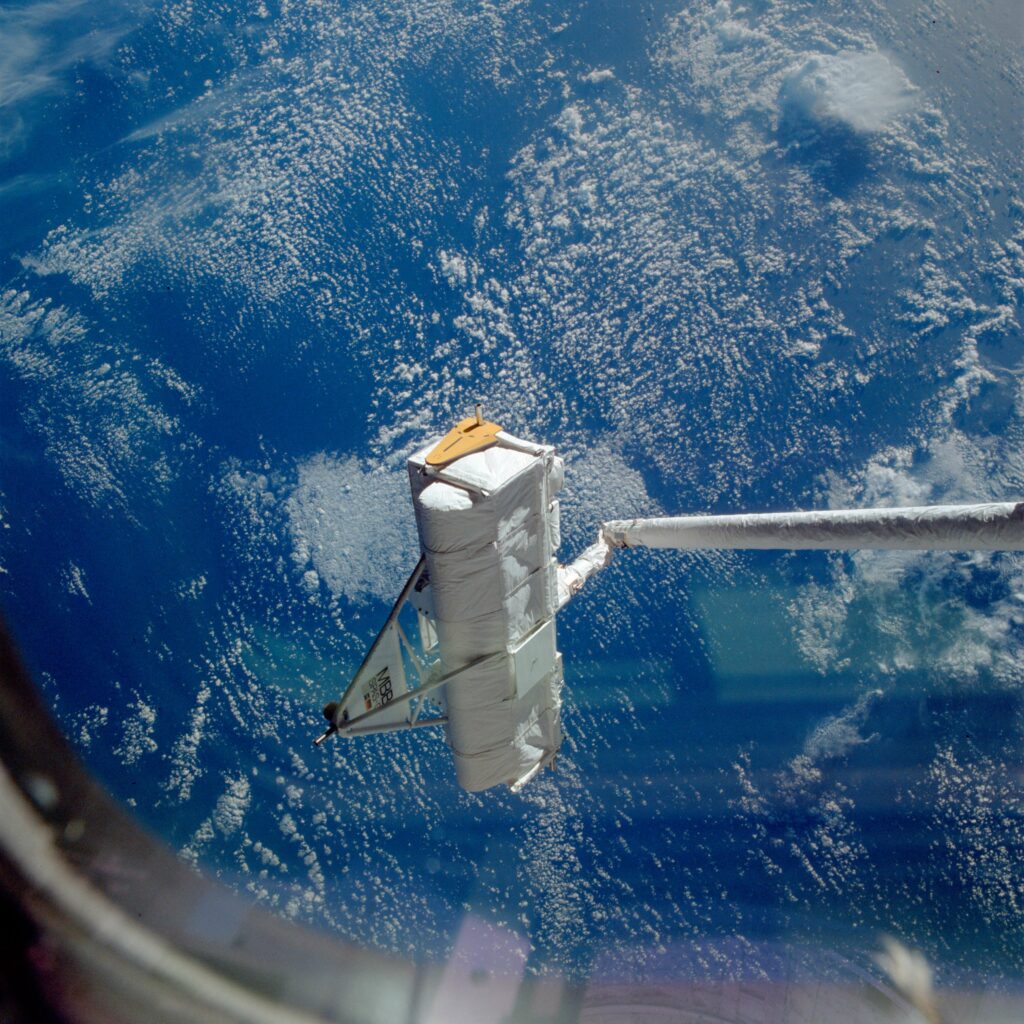

Ride thrived in orbit. Unlike many new astronauts, she didn’t experience any form of space nausea – a little ironic given the crew was meant to test new space-sickness medication, which she couldn’t do. Instead, she dedicated herself to the main task of releasing three new satellites. Two of these were communications satellites, while the third was the Shuttle Pallet Satellite SPAS-01, which would test the formation of alloys in microgravity. During the deployment procedure, she manoeuvred the robotic arm into the shape of a ‘7’ to celebrate the flight.

After a six-day mission, the Shuttle headed home. Bad weather forced it to divert its landing to Edwards Air Force Base in California, but it was one of only a few hiccups in an otherwise flawless mission. Ride’s flight had proved women could not just handle spaceflight but excel at it.

In the years since, there has been a global push to increase female engagement with space and science. Astronaut classes from NASA, the European Space Agency and other nations have included an ever-increasing number of female candidates – many of whom cite both Ride and Tereshkova as inspirations. Just over 70 women have flown in space, out of a total of around 600 people, but the number is growing as more and more women are being assigned to missions. With NASA’s Artemis programme in full swing, it won’t be long until one of them takes “one giant leap for womankind”.

In it for the long Ride

Sally Ride remained dedicated to space long after her barrier-breaking mission

After her flight on STS-7, Ride stayed with NASA and flew a second Shuttle mission, STS-41-G, in October 1984. She was joined on board by Kathy Sullivan, making it the first space mission with two women. It also made Ride the first US woman to fly in space twice and Sullivan the first US woman to perform a spacewalk, though cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya had claimed both of these world firsts a few months earlier.

Ride was scheduled for a third flight, but this was cancelled following the Challenger disaster. Instead, she was appointed to the commission investigating the accident, leading to a more managerial role at NASA, planning the agency’s future.

She left NASA in 1987, taking various university professorial posts, although she continued to work with NASA on outreach programmes. She set up Sally Ride Science to encourage children, particularly girls, into taking up science.

Both presidents Clinton and Obama offered her the role of NASA administrator, but she turned them down.

Ride married fellow astronaut candidate Steven Hawley, but later divorced. After her death on 23 July 2012, her family revealed (with Ride’s consent) that she had been in relationships with both men and women throughout her life and had been with female partner Tam O’Shaughnessy for 27 years, making her the first known gay astronaut.

Ezzy Pearson is BBC Sky at Night Magazine’s features editor. Her book Robots in Space is available through History Press