Is Pluto a planet? If not, why not? What makes a planet a planet, and why was the 9th in the Solar System reclassified as a dwarf planet?

Pluto is not a planet. You’ve probably heard this statement many’s a time, and maybe even wondered why.

Many of us remember being taught at school that Pluto was the 9th planet of the Solar System. So what changed?

In a nutshell, Pluto is considered to not be a planet because of its size, its shape, its orbit and the discovery of many other bodies just like it.

But let’s take a look more closely at the history of Pluto, is re-classification as a dwarf planet and how this whole debate got started.

Pluto becomes a dwarf planet

Pluto’s status was re-classified from ‘planet’ to ‘dwarf planet’ on 24 August 2006 by the International Astronomical Union following a vote of its members.

The official act that took planetary classification from Pluto was IAU Resolution 5A, ‘Definition of a Planet in the Solar System’.

But why was Pluto re-classified, what led to the vote ever taking place, and is Pluto indeed a planet?

Pluto’s journey from its discovery as the 9th planet in our Solar System to its reclassification as a dwarf planet and Kuiper Belt Object is a fascinating tale.

What started off as a curious orbital anomaly in the 18th century turned into the discovery of an object that forced us to rethink our ideas of what a planet should be, and ultimately how our Solar System began.

Let’s take a look back at how Pluto was first discovered.

The discovery of Pluto

By the mid 17th Century, a scientific revolution was in full flow. Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, combined with Newton’s law of gravity, provided astronomers with a powerful tool.

The motions of comets and planets could be determined with absolute certainty. The prevailing view was of a Solar System that ran like clockwork.

By 1821 a curious anomaly had arisen: the recently discovered planet Uranus was not behaving as it should.

French astronomer Alexis Bouvard published tables of Uranus’s position, but found that the planet frequently strayed from its predicted path.

He realised these discrepancies implied the presence of a large unseen body, tugging Uranus off course.

Both John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier predicted where this new planet might be, the latter also having theorised the existence of a planet called Vulcan in order to explain Mercury’s orbit.

But it was Johann Galle and Heinrich d’Arrest who claimed victory, and the discovery of Neptune on the night of 23 September 1846 went to them.

Mathematicians set to work finalising the details of Neptune’s orbit, but they found the discrepancies in Uranus’s path around the Sun didn’t completely vanish as expected.

Something was still causing Uranus to wander. The problem was of keen interest to Percival Lowell, who had established a large observatory in the frontier town of Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894.

Lowell concluded that Uranus and Neptune were being drawn off course by another more distant planet, which he named ‘Planet X’.

In 1906 he began searching for it, but after a decade Planet X had eluded him and he died in 1916. The new director of the observatory, Vesto Slipher, continued the search.

In 1929, the task of searching for Planet X was given to a recent addition to the Lowell Observatory: Clyde Tombaugh.

The work was hard – at night careful photographs were taken of the sky where Lowell had predicted the new planet should be.

During the day, the plates were analysed using a ‘blink comparator’ – a device that switched back and forth between two photographs taken at different times.

Looking through the comparator, stars remained fixed in position but a planet moving in its orbit would appear in a different location in each plate.

On 18 February 1930, after months of searching, Tombaugh made a discovery: he noticed a tiny dot moving among the background stars of Gemini.

The long search was over – Planet X had been found at last.

How Pluto got its name

Planet X was named Pluto after the classical god of the underworld, but almost immediately there were doubts as to whether Pluto could really be Planet X.

It was very faint, and its disc remained unresolved even in the world’s largest telescopes.

Pluto was obviously small, perhaps only the size of Earth or even Mars. It seemed unlikely it could have much influence over Uranus and Neptune.

Observing the planet was extremely difficult, but a handful of dedicated astronomers continued the work.

Gradually, larger telescopes were constructed and observations showed that Pluto was probably covered with methane-ice.

In 1978, astronomer James Christy’s work led to the discovery of Charon, Pluto’s largest moon.

Charon enabled astronomers to better estimate the mass of Pluto, which was much lower than expected – smaller even than Earth’s own Moon.

The small size, combined with its unusual orbit, began to cast serious doubt as to whether Pluto could really be a planet at all.

The 1990s saw the arrival of CCD cameras, which were much more sensitive to light than photographic film.

They allowed astronomers to see fainter objects and peer deeper into the Solar System.

Using CCDs it became apparent that there were many Pluto-sized bodies out beyond the orbit of Neptune.

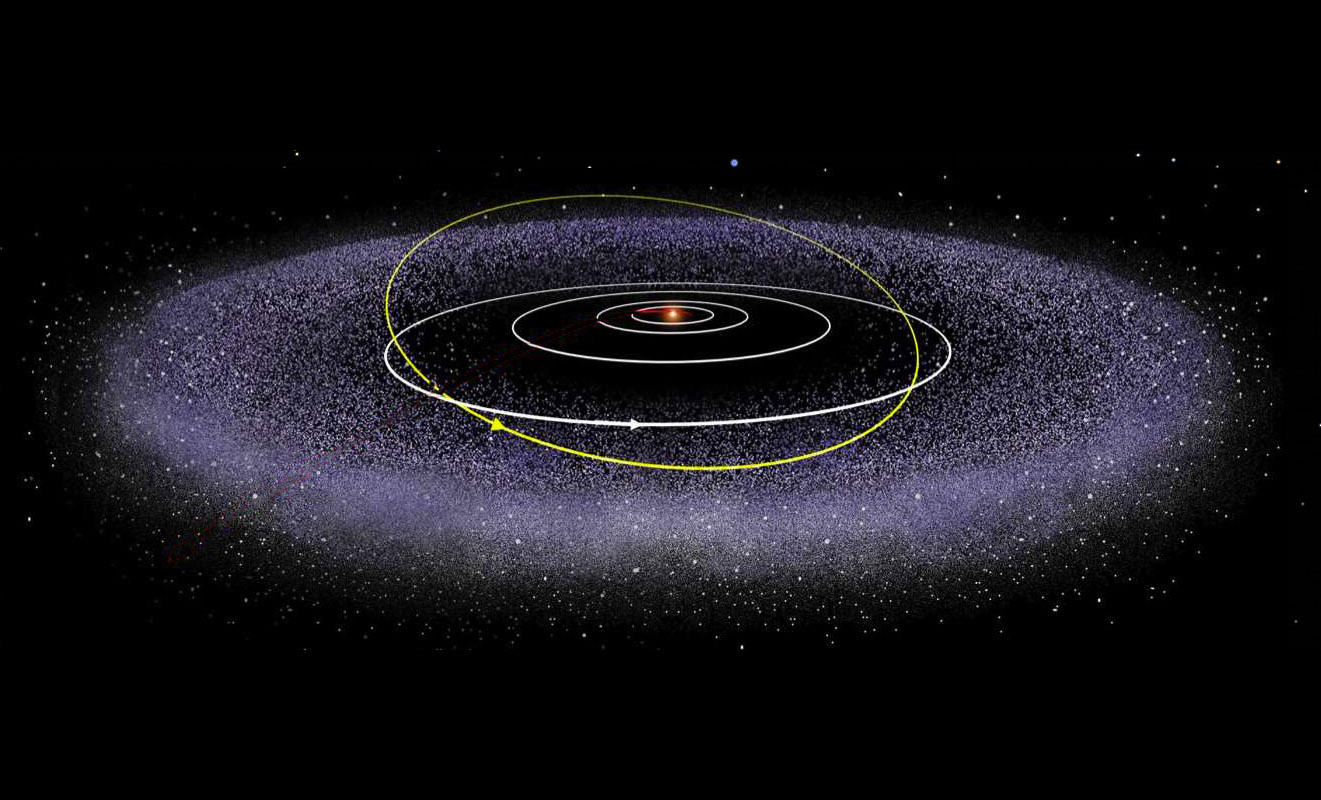

These objects belong to the Kuiper Belt, a vast field of debris left over from the formation of the Solar System, and Pluto was its largest member.

Kuiper Belt Objects are like fossils: their ancient surfaces are like postcards from the past.

From 2002 a host of large bodies was found: Quaoar, Sedna, Makemake and Eris.

Loud astronomical voices began to debate Pluto’s status. It was argued that if Pluto was a planet, were these other objects planets also?

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) settled the matter and defined what was required for an object to be classed as a planet.

What makes a planet a planet

According to the International Astronomical Union, a planet is a celestial body that:

- is in orbit around the Sun

- has sufficient mass for its gravity to overcome rigid body forces so it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape

- has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

One of the conditions is that all material must be cleared from the object’s orbit, something Pluto hasn’t done due to its small size.

Pluto received a new classification: it was a dwarf planet, but this decision is not without its critics.

Pluto may have been demoted, but it plays a vital role in understanding the conditions of the early Solar System.

Arguments for Pluto as a planet

Many argue that if Pluto were to be classed as a planet then so too would many other objects in the Kuiper Belt, and the planet count in the Solar System would rise dramatically.

But what about the arguments in favour of Pluto being recognised as a planet once more?

Pluto was named a planet when discovered

Some argue to keep Pluto as a planet for sentimental reasons: for much of its history, it has been thought of as a planet and therefore should continue to be so.

Issues with the IAU Resolution

Some astronomers point out that there are inconsistencies in the wording of Resolution 5A – while it is true that Pluto hasn’t cleared its orbit, neither has Earth or Jupiter.

Earth orbits with 10,000 near-Earth asteroids, while 100,000 Trojan asteroids lie within Jupiter’s orbit.

One could argue that both Jupiter and Earth also fail the IAU definition.

It’s large enough to be a planet

Those who hold this view say that a better definition of what a planet is might be to say that any object orbiting the Sun that has a surface area greater than 1,000km can be called a planet.

If this definition were to be adopted both Pluto and Eris would be classed as planets.

This article originally appeared in the August 2015 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.