Facts about Mercury transits, including when they occur and photos of the most recent events.

Did you know that there are just two times of year that a transit of Mercury can happen?

Mercury, the innermost world of the Solar System, can only cross the Earth-Sun line of sight within a few days of either 8 May or 10 November.

The next transit of Mercury will occur on 13 November 2032.

When is the next transit of Mercury?

Find out when the next Mercury transit is happening via our table below.

| Date | Universal time | Separation |

|---|---|---|

| 7 May 2003 | 07:52 | 708” |

| 8 Nov 2006 | 21:41 | 423” |

| 9 May 2016 | 14:57 | 319” |

| 11 Nov 2019 | 15:20 | 76” |

| 13 Nov 2032 | 08:54 | 572” |

| 7 Nov 2039 | 08:46 | 822” |

| 7 May 2049 | 14:24 | 512” |

| 9 Nov 2052 | 02:30 | 319” |

| 10 May 2062 | 21:37 | 521” |

| 11 Nov 2065 | 20:07 | 181” |

| 14 Nov 2078 | 13:42 | 674” |

| 7 Nov 2085 | 13:36 | 718” |

| 8 May 2095 | 21:08 | 310” |

| 10 Nov 2098 | 07:18 | 215” |

Mercury transit quick facts

Mercury is so far away from us and so much smaller than the Sun that during a transit of the Sun it appears tiny against the solar disc, unlike the Moon during a solar eclipse.

However, transits of Mercury are visible from the entire day-lit hemisphere of Earth when they happen, whereas solar eclipses are viewable only from within a narrow track.

Mercury also travels through space faster than Earth, and its incredible orbital speed is why Mercury was named after the messenger of the gods.

When we see it moving across the Sun we are glimpsing its forward motion, rather than the changing perspective resulting from the Earth’s motion.

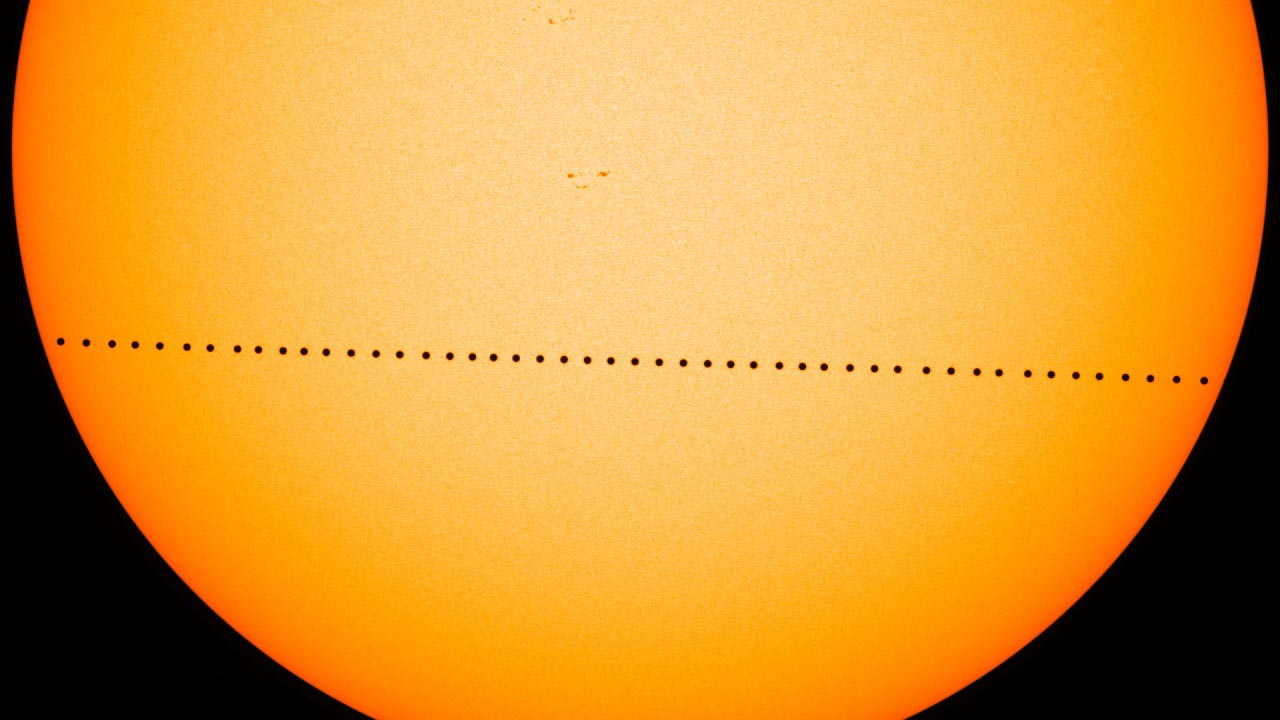

What a Mercury transit looks like

When watching a transit of Mercury you should see the planet, in Sir William Herschel’s words of 1786, as “a very black, round spot”.

It may be noticeably darker than any sunspots, though small, dark objects on a bright background are hard to compare.

If you are watching during the start or the end of the transit, look carefully at the moment when the full disc of Mercury is touching the inside edge of the Sun’s disc (only three minutes after the beginning, or three minutes before the end of the transit).

You may experience the momentary impression of a teardrop joining Mercury to the sky beyond the Sun.

This ‘black drop effect’ is caused by optical defects and is more prominent when our atmosphere is turbulent.

When do transits of Mercury happen?

There are 13 or 14 transits of Mercury over the course of a century. Transits of Mercury always occur in May and November.

What makes them so oddly regular? It’s to do with the eccentricity of Mercury’s orbit and the resonance it has with Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

Mercury has a more eccentric orbit than any other planet, being 0.31 AU from the Sun at the closest point in its orbit (perihelion) but 0.47 AU away at its furthest point (aphelion).

It rotates exactly three times for every two orbits round the Sun.

This is described as a 3:2 spin-orbit coupling, and almost certainly results from the strong tidal forces experienced as a result of Mercury’s changing distance but general proximity to the Sun.

It rotates slowly, bringing opposite hemispheres to the sub-solar point at alternate perihelia.

This results in its day length (measured from sunrise to sunrise) being twice as long as its year, which lasts 88 Earth-days.

Mercury’s apparent size changes by up to 20% and that’s a function of it having the most eccentric orbit of all the planets of the Solar System.

When we see a transit of Mercury in May, it’s while Mercury is closer to Earth and so it has a 12 arcsecond disc.

In November, the transits occur when Mercury is closer to the Sun so the planet appears slightly smaller from our perspective, about 10 arcseconds.

At 88 days, Mercury’s orbit of the Sun is almost a quarter of that of Earth, which means it’s close to being in orbital resonance with Earth, hence the transits occur at the same times of year… for the time being.

The timing between them will drift and though they occur in May and November now, that will change in centuries to come. But they’ll always be six months apart.

How to observe a Mercury transit

It is dangerous to look directly at the Sun, and for a transit of Mercury, there is absolutely no point in doing so!

Mercury’s apparent diameter as it crosses the Sun’s disc is too small to see without magnification, and so eclipse glasses designed for looking through with the naked eye will be no use, nor will pinhole-based gadgets.

Mercury will look smaller than a large sunspot, but will not be too hard to see with a little help.

If you have access to a solar telescope (your local astronomical society may have one) you will be well catered for.

Otherwise, watch the safety advice video on the Open University website revealing how to watch a transit of Mercury and get hold of a mirror and lens-based ‘solar scope’ that projects an image onto the inside of a box.

If you have binoculars or a small telescope but don’t have specialist solar filters to cover the objective lenses, you can still use them to project an image of the Sun onto a white card held about 0.5m beyond the eyepiece.

You can tell when your telescope is aimed directly at the Sun without looking through the eyepiece by manoeuvring it until the shadow of its tube is circular.

Who was first to observe a Mercury transit?

Solar transits of Mercury are more common than a transit of Venus.

The first observation of a transit of Mercury was achieved on 7 November 1631 by the French Jesuit astronomer Pierre Gassendi (above), thanks to a successful prediction by Johannes Kepler.

There is no record of a transit of Venus having been observed until 1639, even though those can be seen by the naked eye (at the risk of damaging your eyesight).

Edmond Halley observed a transit of Mercury while at St Helena on 3 May 1676, and realised that if observers at known but distant locations were to record the same transit, the parallax would give the information required to deduce the scale of the Solar System.

That’s why James Cook was sent to observe the 3 June 1769 transit of Venus from Tahiti.

Less well known is that the expedition’s astronomer Charles Green, along with Cook himself, observed a transit of Mercury on 9 November of the same year, from the shores of Mercury Bay in New Zealand.

Green later fell ill, and died soon after putting out from Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) in 1771, but is credited with being the first to note that Mercury’s crisp outline during transit demonstrates that the planet must have little or no atmosphere.

Sir William Herschel caught only brief glimpses of the 4 May 1786 transit through cloud, but had better luck on 9 November 1802.

Pictures of the transit of Mercury

Below is a selection of images of recent Mercury transits. For more info on planetary astrophotography, read our guide on how to photograph the planets.

And don’t forget to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.