See the gas giant through a telescope and observe its weather patterns, large moons and Great Red Spot.

If you’ve ever taken the time to observe Jupiter through a telescope you’ll notice just how amazing it looks through even a modest telescope.

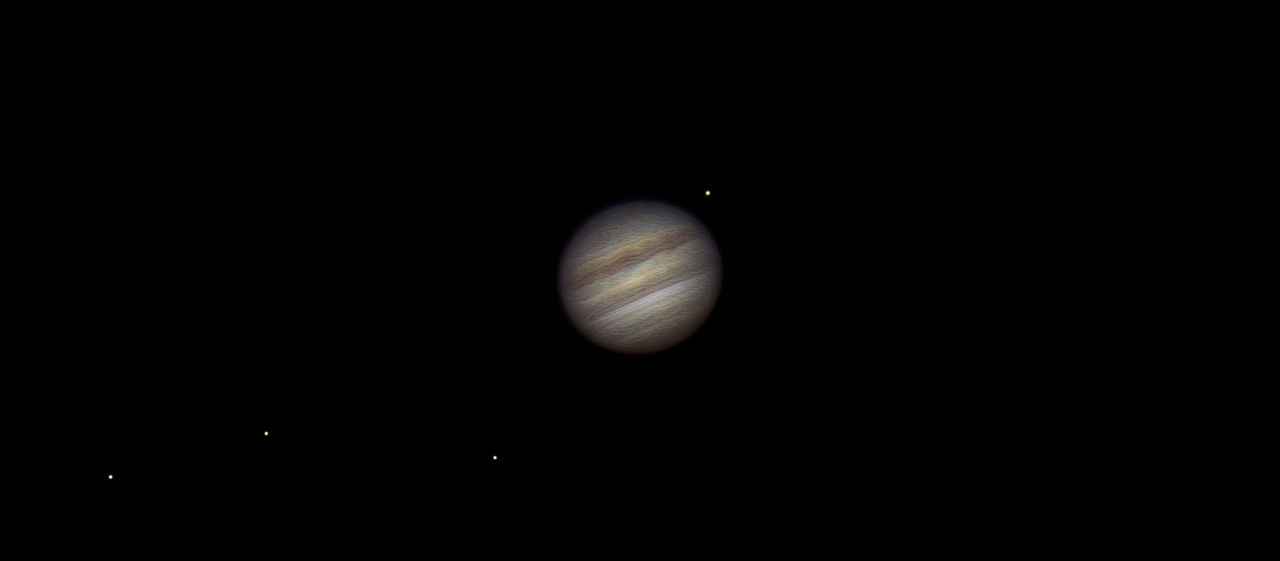

You can easily see Jupiter’s Galilean Moons through a telescope, for example.

A telescopic view also reveals Jupiter to be crossed by dark belts and brighter zones.

The zones are composed of ice crystals higher up in the stratosphere.

Darker features tend to be lower down in the warmer depths. These belts and zones are governed by powerful jet streams, keeping them in place.

A 3-inch telescope scope will reveal Jupiter’s two main equatorial belts and the polar shading.

A 6-inch telescope will show Jupiter’s temperate belts and zones, along with the brownish hues of the largest belts.

Use the diagram below to help you discern what you’re seeing when you observe Jupiter through a telescope.

Jupiter’s gassy atmosphere

Perhaps the most striking thing about a view of Jupiter through a telescope is just how alien it is.

There’s no solid surface on which to stand and gaze out across the Solar System.

Jupiter is a gas giant: when we observe Jupiter through a telescope we see the top of a tumultuous, extensive atmosphere.

If we could venture down through the planet, we’d have a fearsome journey.

At first it would be easy going as we drifted through a cloud deck of ammonia-ice crystals, and later, ammonium hydrosulphide.

But in the lowest cloud deck (composed of water), winds really pick up at speeds of 100 metres per second.

As we continue to fall, pressures and temperatures become extreme, to the point that hydrogen and helium are squashed into an odd substance called ‘metallic hydrogen and helium’.

This churning metallic ocean gives Jupiter a substantial magnetic field: if we could see it in our skies from Earth it would be about the size of the full Moon.

Setting up a telescope to observe Jupiter

If you’re going to observe Jupiter through a telescope, set it up so your view of the part of sky where Jupiter will be is free from obstructions.

Have your telescope ready for observing half an hour or so before you plan to begin looking at Jupiter.

This half-hour will give your telescope the time to reach the same temperature as the air outside.

It will reduce air currents within the tube, giving you more stable views that won’t dance about in the eyepiece.

Using a small telescope

A view through a small telescope will show you Jupiter is a very alien world indeed.

When you look at Jupiter all you’re seeing is the top of a very thick and very active atmosphere.

The planet is a gas giant and has no solid surface, which means making a map of it is a strange business.

After all, maps depend on surface objects having fixed locations that never change.

On Jupiter, features drift across the face of the planet at a rate determined by whichever jet stream they happen to lie in.

Since all this chaos does for geography what the artist MC Escher did for geometry, astronomers have devised a way of mapping Jupiter’s atmosphere.

The planet is split into two regions: an equatorial region called ‘System I’ that rotates completely in nine hours, 50 minutes, and the rest of the planet, called ‘System II’.

This rotates completely in nine hours, 55 minutes: the fastest rotation of any planet in the Solar System.

Within Systems I and II are different belts and zones, the names of which are shown in the diagram at the top of this article.

With a magnification of about 150x, Jupiter will look squashed and will display a light lemon-curd colouration.

You will be able to see the two prominent dark bands, the southern equatorial belt and the northern equatorial belt.

Jupiter’s dusky poles will be visible and you may be able to make out another couple of belts and zones depending on the seeing (how still the air in the atmosphere is).

At these magnifications, the Great Red Spot should be visible if you’re lucky enough to get good observing conditions (more on the GRS later).

It’s possible to make out darker sections in Jupiter’s northern equatorial belt and bright white ovals in the equatorial zone with a small 4.5-inch reflector.

If you have this size of telescope, you’ll be able to make useful observations of the planet.

If you have a telescope with an aperture of 6 inches or more, you’re in for some truly stunning views of Jupiter.

You’ll see a wealth of detail, such as the southern equatorial belt split by a bright zone, and the northern equatorial belt will be a hive of activity with festoons and spots.

Observe Jupiter’s weather patterns

There are always several short-lived weather systems on show.

Bright spots, festoons (darker markings stretching diagonally away from the main bands) and dark barges (lozenge-shaped regions that occasionally merge together) populate the belts and zones.

Measuring how much these objects drift means you can infer the speed of the jet streams in Jupiter’s roiling atmosphere.

It’s like dropping a twig into a stream and measuring how fast the twig is moving; therefore how fast the stream is flowing.

Indeed, before the advent of space probes, this was how the wind speeds on Jupiter were measured.

Up the aperture to observe Jupiter through a telescope

Through 8-inch and larger telescopes, the view of Jupiter is really spectacular.

A number of more subtle belts and zones are revealed – on a good night the details can be overwhelming!

White ovals appear in the South Tropical Zone, swirling structures in the equatorial belts, and festoons (a darker cloud that links two neighbouring belts) streak across the Equatorial Zone.

With an 8-inch reflector you’ll see lots of detail on Jupiter, such as the colours of the belts and a good view of the Great Red Spot.

Use averted vision on Jupiter’s cloud bands and other features to glimpse extra detail in the swirling atmosphere.

With a large telescope, you can also try your hand at taking images of Jupiter’s roiling northern equatorial belts.

And look for white spots near the polar regions.

Take your time

One thing to remember when you observe Jupiter through a telescope is you shouldn’t expect to see fine details instantly.

For good results, spend time – maybe as much as 15 minutes – looking at the planet and taking it in.

Use magnification suitable for the seeing conditions: around 180x is enough to bring out fine details on an average night.

If you want to make a drawing of Jupiter, finish it in under 12 minutes, otherwise rotation will have moved the features on.

Spend six minutes drawing the main belts, then add the final details in the remaining time.

Use telescope filters

Colour filters can enhance many of Jupiter’s features through your telescope eyepice by increasing their contrast.

Use a blue filter to bring out details in the belts, or a red filter to sharpen up the zones.

A yellow filter generally sharpens most things on the disc – it’s a good all round filter for Jupiter.

Observe the Great Red Spot

The most famous artefact of Jovian meteorology is the Great Red Spot.

This is a vast hurricane three times the size of Earth that has been raging in the planet’s South Tropical Zone for hundreds of years.

The spot varies in colour and intensity and sometimes fades. When it has a strong orange colour it should be visible in a 4-inch scope.

Larger telescopes will reveal subtle structure inside the spot on a good night. Try using a light-blue filter to help bring out detail.

Observe the Galilean moons

Jupiter has four large satellites: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

They’re called the Galilean moons, Galileo discovered them using a telescope less powerful than the average pair of binoculars.

Before the Voyager spacecraft visited the system, the moons of Jupiter were thought to be cold, dead worlds.

We now know they’re some of the most fascinating bodies in the Solar System, alive with geology, sculpted by gravity and cataclysmic impacts.

In a small telescope, Galilean moons appear as bright star-like points, but look at them in an 8-inch instrument and they apear as tiny discs.

Jupiter’s moons cast shadows into space, and often they (and respective shadows) pass in front of the planet in an event called a transit.

Transits are great to watch: Ganymede’s shadow can be seen in a 2-inch scope under good conditions.

And certainly a 3-inch aperture is enough to show the shadows of the others.

Sometimes more than one of these moons makes a transit at the same time.

It’s remarkable just how much quicker Io’s shadow crosses Jupiter’s clouds compared to that of outermost Callisto.

See if you can spot a transiting moon. To check when these events occur, read our guide on how to see the Galilean moons and use planetary observing and imaging software WinJUPOS.

Experiment with different equipment

I’ve produced sketches below to show how Jupiter appears through different equipment: binoculars, small/medium telescope and large telescope

Binoculars

A pair of binoculars will reveal Jupiter and its four largest Moons.

Night after night you will be able to observe the moons, tiny star-like points, change position as they orbit Jupiter.

You’ll also be able to catch the planet moving against the background stars.

Small/medium telescope

In a small telescope, Jupiter is transformed into a yellow disc that looks appreciably flattened.

You’ll see a bright Equatorial Zone separating the main equatorial belts.

With a medium telescope, look for bright structures in Jupiter’s larger South Equatorial Belt just following the Great Red Spot. A light-blue filter will help.

Large telescope

Myriad fine, slowly changing details will be apparent when you observe Jupiter through a large telescope.

You can study the small storms and clouds within the main belts and monitor subtle colour changes in the zones.

Locate Oval BA, a small version of the Great Red Spot also in the South Tropical Zone.

Submit your Jupiter observations for science

When you observe Jupiter through a telescope, don’t just let your observations sit there doing nothing.

You can send your data the Jupiter section of the British Astronomical Association or the Society for Popular Astronomy.

Then your careful observations of Jupiter can be put into the body of scientific data on the planet.

And you’ll be contributing real citizen science that helps us all understand more about our Solar System.

Jupiter is a planet that never disappoints: it’s constantly changing and no two views are ever quite the same. It’s a world that you can return to again and again.

Have you observed or photographed the planet Jupiter? Let us know how you got on by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com