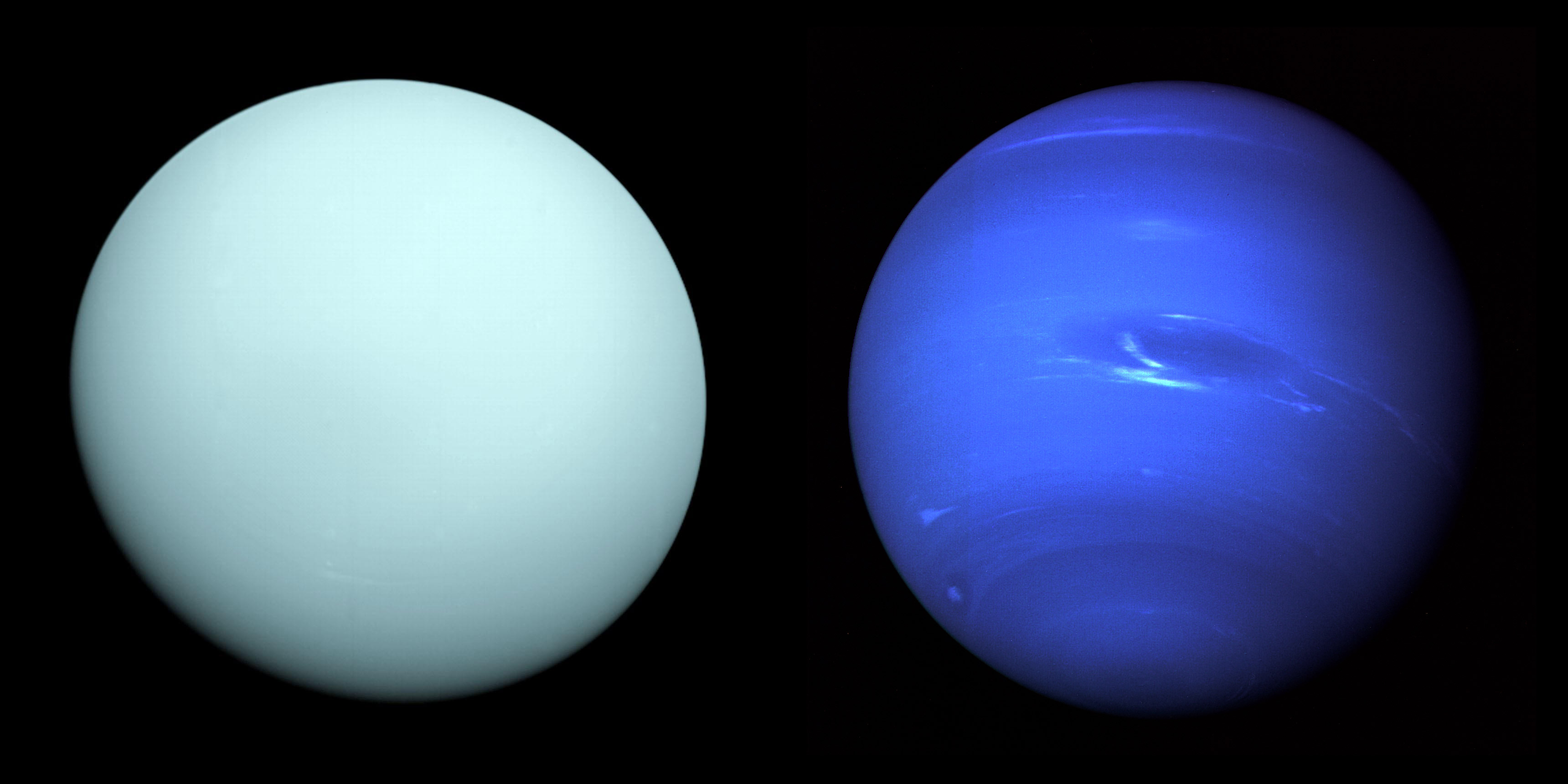

If it’s not furthest from the Sun, why is Uranus the coldest planet in the Solar System?

Uranus, seventh planet from the Sun, is one of the giants of the Solar System and is the coldest planet in the Solar System.

Uranus‘s diameter is more than 51,000km at the equator, and one of the big mysteries is that it doesn’t give out much heat.

Temperatures in Uranus’s cloud tops average –224°C, making it the coldest planet in the Solar System, even though it’s closer to the Sun than Neptune.

Neptune has an average temperature of -214°C, making it the second coldest planet in the Solar System

All the planets of the Solar System radiate primordial heat left over from their formation, but Uranus appears to be emitting very little heat.

It is up to astronomers and planetary scientists to work out why.

Uranus was discovered by William Herschel in Bath, UK in 1781, yet to date only one space probe has ever visited.

That was Voyager 2, which flew past fleetingly in 1986.

In the years since then, we have glimpsed changes in Uranus’s rings and atmosphere.

Very little weather was detected at Uranus by Voyager. But recent observations from the ground have detected quite active weather systems.

We need to understand what has changed and why.

Astronomers tend to group Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune together, but the latter two lie much further out in the Solar System.

Uranus orbits at a distance of 2.86 billion km (1.78 billion miles) from the Sun.

Take a closer look, and Jupiter and Saturn are dominated by hydrogen and helium with small rocky cores.

Whereas Uranus and Neptune are made up of a lot more rock and ice.

There is also more water and methane in their atmospheres and their solid cores are much larger.

Why is Uranus the coldest planet?

Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun in our Solar System, so surely it should be the coldest. We know this is not the case: Uranus is the coldest planet. But why?

One suggestion is that convection in its atmosphere is somehow inhibited so there are no large-scale over-turning motions like in other planetary atmospheres.

Another is that Uranus lost most of its primordial heat early in its life.

An odd feature of Uranus is that its axis is highly tilted to its orbit by over 97° so that it rolls around with its pole lying in its orbital plane.

It is thought that something the size of Mars or Earth may have hit Uranus in the early days of the Solar System and knocked it onto its side.

That might also have caused a massive loss of primordial heat.

And with so little heat coming up from inside the planet, Uranus’s atmosphere is completely driven by sunlight.

The large tilt in its axis also produces very unusual seasons on Uranus in its 84-year orbit around the Sun.

One pole gets continual sunlight for 42 years while the other is in darkness, and then the situation is reversed for 42 years.

The atmosphere is very strongly affected by this: a situation we don’t find anywhere else in the Solar System.

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus, just one hemisphere was being illuminated by the Sun.

But in 2007, Uranus reached one of its equinoxes when the equator was getting all the sunlight. This changed the dynamics of the atmosphere.

Uranus’s rings

Uranus’s ring system is quite different to the ones we find at Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune.

The rings are very dense, narrow arcs and they have been seen to change since Voyager 2.

One of the rings has moved in closer to the planet and new rings have been observed.

A tiny moon called Mab lies at the core of one of these rings and seems to be feeding it material.

We also need to know more about how Uranus’s own aurora is produced by its magnetic field.

It will take many years for a probe to reach this distant ice world, but returning to Uranus and Neptune would enable us to solve some of their many mysteries.

This article originally appeared in the May 2011 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.