BBC Wildlife 60 years

60 favourite wildlife hotspots

To celebrate our 60th birthday, we have a tempting round-up of special places to visit around the UK

SIXTY YEARS AGO, BBC WILDLIFE MADE its first appearance as the magazine Animals. To celebrate this special birthday, we’ve asked 60 people from our wonderful network of writers, presenters, photographers and conservationists to share their favourite places in the UK for wildlife. As the nominations have flooded in for exquisite forests, lofty hills, shimmering wetlands and windswept shores across the country, we’re reminded that, despite the pummelling nature has taken in recent decades, there are still many corners of the UK where wildlife thrives.

We want your say, too. Vote for your favourite of the 60 nominated spots. And if there’s somewhere else that’s special to you, email or write to us..

Blakeney Point, Norfolk

WHERE LAND AND SEA collide, nature is wild and dynamic. Shifting shores are shaped by the tide each day, no two the same. Blakeney Point, on the North Norfolk coast, offers the remoteness and solitude I often crave. Sea breezes blow the cobwebs away, the eyes can gaze for miles to the horizon and there is limitless fresh, salty air.

As well as a dramatic landscape, space to think and miles to explore, it’s the wildlife that makes this National Trust National Nature Reserve so magnificent. There’s a constantly changing cast of plants and creatures throughout the seasons, so it’s rewarding at any time of year. Between Halloween and New Year, grey seals take over the beach. Hundreds and hundreds of pups are born annually, their white fur contrasting with the speckled coats of the adults. They’re best admired by boat to avoid disturbance, and the sound of their calls is both serene and slightly spooky.

Summer is all about the seabirds. Tons of terns arrive here from Africa to nest in dense colonies on the ground, foraging at sea for sandeels and small herring. I love watching them plungedive into the water, gracefully folding their angular wings and emerging with a shining, silver fish.

When I worked as a ranger at Blakeney Point, the spring and autumn bird migrations were always a highlight. Birds are on the move in dramatic fashion and almost anything can turn up, from tiny warblers to awesome raptors. I could never relax, though, in case I missed something special flying right over my head.

Goredale Scar, Yorkshire Dales National Park

THERE ARE PLACES YOU GO FOR grand spectacle, and others where the wonder is in microcosms. The Yorkshire Dales offers superlatives of both. Here, the land shows its bones – in this case they are made of limestone, shaped and hollowed and made wondrous by the movement of water, which both weathers and redeposits. I especially love the mad hopscotch of limestone pavement around Malham and Ingleton, where blocks of weathered stone are exposed to excoriating wind, sun, rain and ice, but where sheltered crevices contain worlds as humid and green as a Victorian fernhouse.

Then there are the scars – enormous, water-worn ravines with a distinctly Middle Earth vibe. Perhaps the most epic of these is Goredale, with two cascading waterfalls, tenacious yews, carpets of luxuriant mosses and one of the most thrilling public footpaths in England, which takes you directly up to one of the falls. As you explore, listen and look out for curlews, lapwings, golden plovers, peregrines and brown hares.

New Forest, Hampshire

NOT MUCH OF SOUTHERN England feels wild and remote, but if the mood is right – acold winter day or during an angry storm – you feel a frisson of isolation here, particularly around Bolderwood and Fritham. The whole national park, with its ancient woodlands, plantations, heaths and bogs, and with the ponies and other livestock, is distinctly different from the surrounding land and feels special. Its wildlife is special, too – Ihave seen everything from honey buzzards to toadstools that could almost kill you at a glance. I have been at dawn, by night and amidst seething crowds of tourists, over whom flew hawfinches and crossbills. One favourite memory is spying a lesser spotted woodpecker, the icing on the nervous cake of a group-of-six pandemic walk. The exhilaration pointed to a happier future.

Dartmoor, Devon

THERE ARE FEW MOMENTS IN life that can compete with a still, sunny day perched on a granite boulder while contemplating the delights of a Rhôs pasture.

Rhôs means ‘moorland’ in Welsh, but is so much more than that. I tend to think of moor as an impoverished place, a landscape beaten by the hand of man and the foot and tooth of beast. But in this soggy, boggy corner of Dartmoor National Park, there’s a biodiverse, banging party going on.

This waterlogged grassland habitat is a living pallet of colours provided by bog grasses, asphodels and sphagnum mosses, and is a haunt of both the common and rare. Carnivorous sundews lie at my feet, their scarlet hairs reaching for clumsy insects.

A hobby snatches fat emperor moths, their wings tumbling like confetti as the bird rips them off and feeds on the wing. I see marbled white and common blue butterflies and the blooms of butterfly orchids and ragged robins, and can hear skylarks and tree pipits as well as crickets scraping the day away. In the dimpsy light of evening, this landscape becomes the hunting ground of the nightjar, its mechanical purring intertwining with the drumming of snipe.

A Rhôs pasture experience transcends that Welsh word. It is a rainbow of life that fills ears, eyes and nostrils; a flowering, fluttering, scratching, melodious place that never fails to instil in me the thrill of being alive.

Scaur Glen, Dumfriesshire

THE SCAUR WATER RISES IN Polskeoch on the Southern Upland Way, bubbles through moorland, meanders through sheep pasture and then tumbles through wooded riverbanks to Penpont. As a PhD student I spent three summers in this glen; 35 years on, summer still draws me back.

Walking the Scaur River’s lower stretches, you can glimpse the white bib of a dipper bobbing on a boulder or the flitting of a grey wagtail at the water’s edge. In spring, the woodlands welcome pied flycatchers and redstarts returning from Africa.

Upstream, the glen opens up, the water calms and its shingle banks host another migrant, the common sandpiper. This wader’s gentle manner and muted plumage contrast with the red, white and black of the oystercatchers breeding in nearby fields.

Above the treeline, in wilder moorland, the ever-narrowing glen is guarded by the steep rockface of Hallscaur Craig, the occasional site of breeding peregrines. Now it feels remote and bleak, the silence broken only by the call of a meadow pipit or wheatear. One river, one glen, capturing so much magic of our natural world.

Lundy, Devon

WILDLIFE-WATCHING destinations don’t get much better than Lundy. Lying 18km off the North Devon coast, with the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Bristol Channel to the east, this little island hosts a variety of rarely seen Mediterranean-Atlantic species.

On my most recent trip, we were accompanied by a pod of common dolphins on much of the two-hour boat journey from Ilfracombe. Spring birdwatchers are in for a treat with resident shags, peregrines, rock pipits and ravens joined by breeding visitors such as oystercatchers and skylarks. From April to late July, nesting seabirds arrive, including growing numbers of Manx shearwaters. The island even has its own endemic cabbage!

As a diver, my best encounters have been in the water, particularly in the sheltered eastern coves. The local grey seals are accustomed to humans and are incredibly inquisitive, playing hide and seek among the kelp and using their sensitive whiskers to explore your diving equipment. It’s an experience that I will never tire of.

River Chet, Norfolk

THE FORMAL SET-PIECE nature we find in our reserves from hides and lookout points is incomparably great, but it’s also good to catch nature off its guard, not as a treat but as part of daily life.

Whenever I can, I take my kayak out on the River Chet. It’s not a pilgrimage spot for naturalists, but once there you can encounter nature on a come-as-you-are basis. It can be spectacular: otters at play in the water; marsh harriers sky-dancing overhead; the vivid blue flashes of kingfishers.

But a paddle without highlights-reel stuff is just as good: banded demoiselles dancing along the edges; the voice of Cetti’s warblers; the summer extravagance of purple loosestrife and hemp agrimony along the banks. There you are, sitting on the water like a duck, politely giving way to swans, swifts dropping down to sip water a yard or two in front, deer barking on the banks and chevrons of waterbirds flying overhead in winter.

I have paddled energetically through films of ice with my breath smoking like a dragon, and I have drifted on indolent summer evenings. I have noted the first signs of spring and the early onset of autumn. As I paddle, I cease to be an observer and become instead a participant, just one of the crowd moving along our river under our enormous Norfolk sky.

Chanonry Point, Ross and Cromarty

FANCY A CLOSE ENCOUNTER with a dolphin? Easy. All you have to do is go to Chanonry Point, on the Black Isle just north of Inverness, and stand on the shingle beach. Chances are you’ll see them chasing salmon just a few metres away.

There is a resident population of some 200 bottlenose dolphins along the east coast of Scotland; many of them frequent the Inner Moray Firth. They have been studied since 1989 and researchers know most (if not all) of them by name. Chanonry Point is a hotspot – the Moray Firth narrows, channelling the dolphins close to shore. They are seen here almost every day in summer and sporadically during winter. Prime viewing time is a couple of hours before high tide, when the rushing currents push through the bottleneck and concentrate the dolphins’ salmon prey close to shore.

Chanonry Point can get busy in summer, and while I’d normally travel in the opposite direction to hordes of people, I make an exception for this very special place.

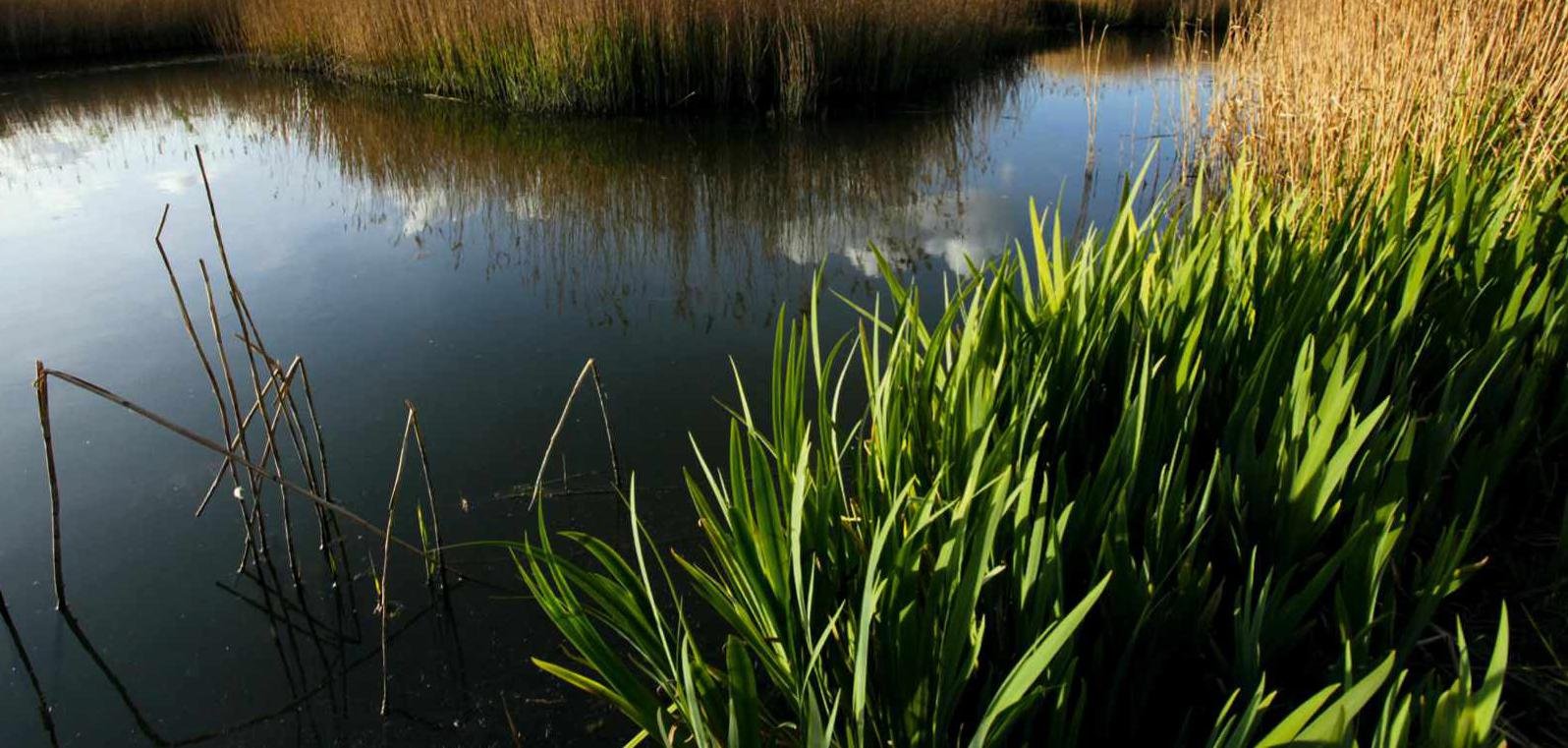

Ham Wall, Somerset

THE MAGNIFICENT SOMERSET Levels has been my local patch for the past decade, and it’s stuffed to the gunnels with wildlife. The jewel in its crown is RSPB Ham Wall, whose expansive reedbeds, open water and wet woodland deliver year-round. In spring, you can hear 10 different species of warbler before breakfast; summer is marvellous for dragonflies and butterflies; and autumn brings wildfowl and waders from the north – whistling wigeon, tiny teal and rafts of lapwing. As winter beckons, the reserve is dominated by one event: vast, morphing flocks of starlings at dusk, one of the most mesmerising spectacles in nature.

Frays Farm Meadows, West London

THIS DELIGHTFUL RESERVE IS one of my favourite places. A SSSI managed by the London Wildlife Trust, its wet grazing meadows are a hinterland of sorts, bound by the Grand Union Canal to the west and the roaring A40 to the south.

Frays teems with bird life and I see raptors on almost every visit. Red kites and buzzards soar, while kestrels hover metres above the shrub, anticipating an emerging woodmouse. Hobbies dart through the air in summer, the sunlight illuminating their red ‘trousers’ as they search for dragonflies along the weaving chalk stream. At the same time of year, the vegetation bursts with the songs of warblers – chiffchaffs, blackcaps and whitethroats all belt out a chorus.

My first visit was my most memorable. I witnessed a spectacular emergence of mayflies rising from the stream in their thousands to fulfil their goal of breeding. I never doubt Frays’ ability to surprise.

Middleton Lakes, Staffordshire

THE FIRST TIME I VISITED RSPB Middleton Lakes – or Middy as I call it – I barely knew my blue tit from my great tit. Little did I know that this hidden patch of rustling reedbeds and stretching skies would become a place of learning and escape. Nestled between the urban stretches of Tamworth and Birmingham, Middy reveals wild wonders with every visit, ringing with the squawks of herons, the ‘oi-oi-oi’s of nuthatches and the tapping of woodpeckers.

In spring, Middy is JOY! I’d travel there specifically for my first cuckoo of the year. A good day in May and 10 types of warbler will grace your ears with their song. The hours spent absorbing wild things here are consistently uplifting.

Bass Rock, East Lothian

THERE ARE FEW PLACES IN THE UK that can make you feel like you’ve travelled back in time. Stepping foot in a habitat that’s truly wild and seemingly unimpacted by humans is rare, but Bass Rock is one of those special places for me.

Situated just 2km off the coast in the Firth of Forth, this chunk of carboniferous rock is home to a staggering 150,000 northern gannets during the peak of the breeding season. I’ve been lucky enough to visit twice; both times it was like arriving into a scene from Jurassic Park, with these birds, with angular, 1.8m wingspans, soaring above in their thousands. It’s the largest colony of its kind in the world. Nests are scattered over every available inch, and the sound is overwhelming as adults return from foraging trips. It’s chaotic, and you might leave covered in excrement, but it’s one of the best, most beautiful wildlife experiences out there!

These gannets, like many other seabirds, were hit badly by bird flu in 2022. I have hope that numbers will recover – until then, I’ll continue using Bass Rock as motivation to keep fighting for our precious planet.

Chew Valley Lake, Somerset

I HAVE LIVED IN THE CHEW Valley all my life. My parents would often go birding at the lake and ended up moving to the area. The lake is a beautiful spot – Iused to go past it every day on the bus to school, and I loved watching the birds as we whizzed along.

As a local patch, the lake is fantastic. Besides birding, I go bird-ringing and take part in BTO surveys and nest-recording schemes, as well as the annual Canada geese round-up, which all give me the chance to study birds close-up. It’s also a great destination for casual birders and families wanting to get out of the city. In the past five years, I’ve noticed lots more visible minority ethnic families visiting, drawn by the opportunity to feed the birds, eat fish and chips, explore the easy, pushchair-friendly footpaths and enjoy the views.

Autumn is always an exciting time as there’s the possibility of American waders – autumn 2011 was particularly amazing, with sharp-tailed, white-tailed and pectoral sandpipers and a shortbilled dowitcher. I love all of the lake’s birds – terns, grebes, ducks and egrets – but my favourite is still the bearded tit.

Jurassic Coast, Dorset

THIS STUNNING STRETCH OF coast is a tourist honeypot, but away from the beaches, the chalk hills are one of my favourite UK haunts for butterflies and day-flying moths.

There’s a particularly strong association with butterflies at Lulworth Cove – not only is Butterfly Conservation HQ just a few miles inland, but this is the only specific place in Britain to have given its name to a resident species: the Lulworth skipper. The entire UK range of this diminutive insect is in the tussocky grasslands of south Dorset.

This is a place to sit among the flowers and watch. In summer, the downland shimmers with Adonis and chalk hill blues, marbled whites and six-spot burnets, while dark green fritillaries and graylings zoom past. Moths include the wood tiger, bordered grey and yellow belle, and it’s a great spot for migrants. I once watched a red admiral fly out to sea in a steady, unwavering course – at the exact moment I was talking about butterfly migration for BBC Radio 4.

Strathspey Forest, Cairngorms National Park

CLOSE YOUR EYES AND imagine. An ethereal mist rolls over a mirror-calm peaty lochan, fringed with twisted Scots pines that have stood sentinel for centuries. The dawn silence is punctured by the frantic scurrying of a red squirrel across fissured bark. From somewhere unseen, the mournful, spine-tingling song of a red-throated diver is abruptly interrupted by angry chattering from atop a nearby pine. The Mohican headgear silhouetted against the emerging sun reveals an agitated crested tit.

Goldeneye drakes squabble as they do each spring, their rasping calls and whirring wingbeats a familiar, uplifting soundtrack. Overhead, an osprey drifts silently by, speculating for an early meal.

The Caledonian pine forests of Strathspey are magical places to visit, but these dawn forays have taught me to not only look, but ‘feel’. Pine martens, goshawks and white-tailed eagles are making a comeback to these primeval woodlands, and sitting quietly beneath a weathered granny pine as the first rays of sun warm the air, it’s easy to imagine more: the work of beavers, the distant bugling of cranes and perhaps even the thrilling presence of lynx. These pine woods are not just about what is, but what could be. Close your eyes and imagine.

SHORTS

Bempton Cliffs, Yorkshire

Sheena Harvey, editor of BBC Wildlife, 2015-2019

I love a seabird – and you can’t beat a gathering of ocean wanderers at breeding time. My favourite spot for this spring spectacle is RSPB Bempton Cliffs, where clifftop paths get you up-close to gannets, and viewing platforms provide a glimpse of thousands of nesting guillemots and razorbills on the cliff-face. It’s a full-on assault of the senses!

Y Foryd, Gwynedd

Fergus Collins, editor of BBC Countryfile

Just south west from Caernarfon and its castle is a peninsular that jags into the Menai Straits. This finger of land protects a huge area of mudflats and sand. At high tide it becomes the shallow lake of Y Foryd; at low tide the bay is threaded by eerie creeks beloved by waders and wildfowl. It’s a perfect, timeless wild haven.

Hackfall, Yorkshire Dales

Mark Feather, UK estate manager at Woodland Trust

I’ll never forget my first visit to Hackfall – a wooded gorge full of crumbling ruins – in 1989. I took in the views of the North York Moors, I wandered amid the ferns of Grewelthorpe Beck and I walked the River Ure, the haunt of kingfishers and dippers. I’ve explored it all now, but it’s a place I could never tire of.

Lough Erne, Fermanagh

Colin Stafford-Johnson, BBC presenter

Lough Erne is one of Northern Ireland’s few remaining strongholds for breeding waders. In spring, curlews call, lapwings tumble through the air and redshanks make their presence felt. The reedbeds are full of coughs and squeaks and a gravel island hosts a rare inland colony of screeching sandwich terns. It’s a place where the world appears as it should.

Skokholm Island, Pembrokeshire

LYING 4KM OFF THE SOUTH Pembrokeshire coast and with more designations than you could shake a stick at, Skokholm is a wild Welsh gem. It is less known than its sister island of Skomer, but is nonetheless home to 15 per cent of the world population of Manx shearwaters and 20 per cent of the European population of storm petrels, as well as thousands of puffins, guillemots and razorbills. Choughs, ravens and peregrines all breed here, as do oystercatchers and wheatears. Skokholm also has some of the world’s largest slow worms.

But what makes the island most special is its tranquility. With visitor numbers restricted, Skokholm is far less busy than Skomer and offers the natural solitude so often lacking in the modern world. There is an old Welsh proverb that describes it perfectly: Lle i enaid gael llonydd – ‘a place for the soul to find peace’.

Knepp Estate, West Sussex

THE WONDERFUL THING ABOUT Knepp (the rewilding estate in the grounds of Knepp Castle) is that it’s like stepping back in time. I like to visit early and walk among free-roaming Tamworth pigs and longhorn cattle, looking out for Exmoor ponies, beavers and deer. The dawn chorus there last May was unlike anything I’ve ever heard, with blackbirds and robins mingling with Cetti’s warblers and what sounded like hundreds of nightingales. Who gets to hear hundreds of nightingales these days? Me, at Knepp, that’s who!

In summer, I hear the purring of turtle doves, I watch purple emperor butterflies fight and I’m roused from my tent by the unfamiliar clacking of stork bills. Against a backdrop of climate change and extinction, Knepp is a beacon of abundance and hope. It’s my absolute favourite place for nature.

Avon Gorge, Bristol

MY TOP SPOT IS MY HOME PATCH – immediately accessible and with a richness of biodiversity that matches anywhere in the UK. Partly within Bristol city boundaries, the Avon Gorge includes not only the magnificent limestone gorge itself and the tidal River Avon, but also a triad of special conservation sites, including a National Nature Reserve. Brunel’s famous Clifton Suspension Bridge is what attracts tourists, but that’s just the headline. Beside the bridge it’s possible to see up to 65 bird species that regularly use the gorge (which is also a gull highway) and at night, bats – lots of them, including lesser and greater horseshoes. The cliffs provide nest sites for the celebrity peregrines and ravens.

Leigh Woods, which hugs the west side of the gorge, is a panorama of soft greens in spring and golden hues in autumn, offering rare fungi, bryophytes and trees, including the Bristol whitebeam. Among its rocks and gullies live strange invertebrates, including my holy grail of spiders, the scarce purseweb, Britain’s only tarantula relative. The wealth of floral rarities include the Bristol onion, the Bristol rock-cress and limestone grassland gems from speedwell and squill to bee and fly orchids. There is even a café, complete with sunbathing green-backed wall lizards. What more could you ask for?

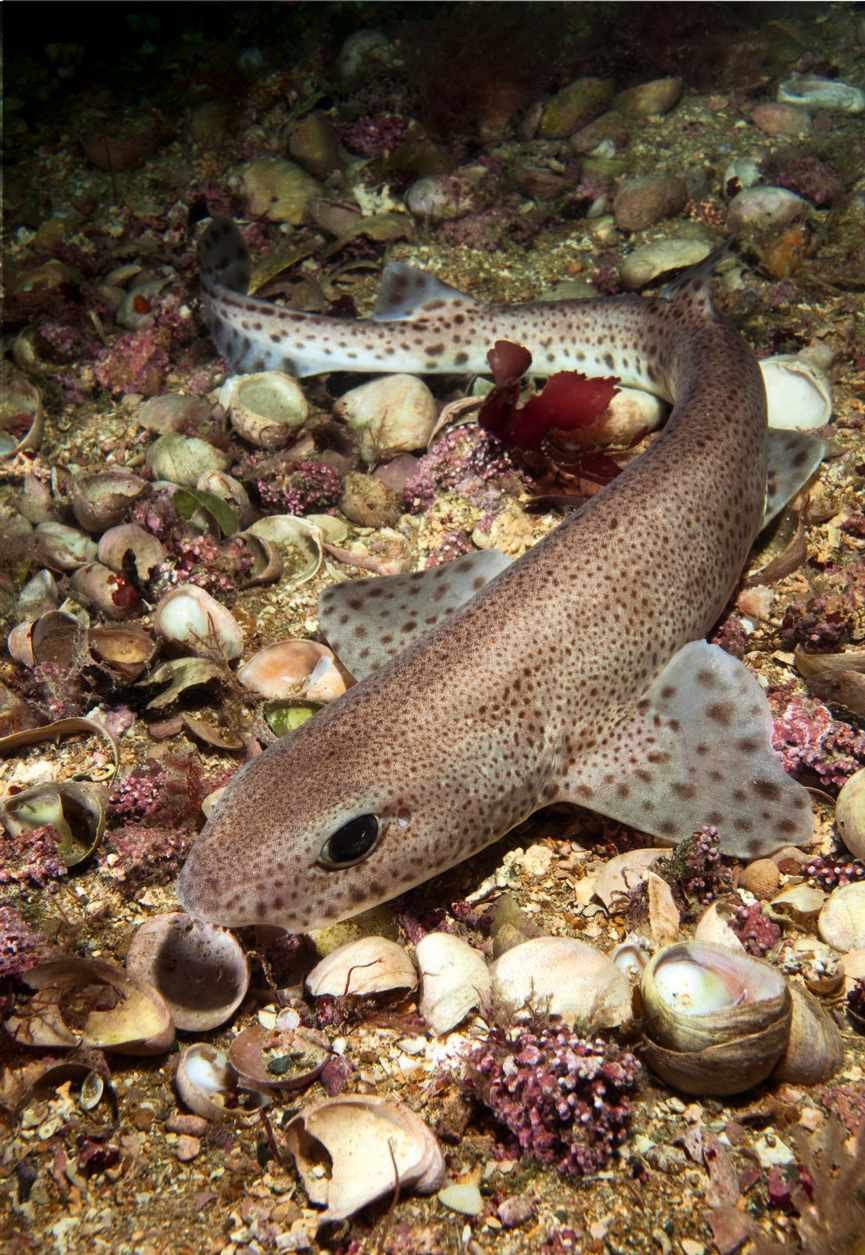

Causeway Coast, Northern Ireland

THE CAUSEWAY COAST IS A wild place of outstanding natural beauty, with dunes, sheer cliffs and, of course, the amazing rock formations of the magnificent Giant’s Causeway. It is a coastline to meander along by land or by sea, keeping an eye out for whales, dolphins and basking sharks.

While studying at Ulster University, I spent some of my most memorable days here, both in and under the water – catching waves at Portrush, snorkelling with curious seals and scuba diving. Dives off the Skerries and below the dramatic cliffs of Rathlin Island have brought me face to face with the dark eyes of conger eels peering out of shipwrecks and the steely shark eyes of dogfish patrolling stony reefs. People ask me why I choose to dive in such cold water, and the answer is simple: the Causeway Coast is as beautiful underwater as it is above. Spending time exploring from the sea enthralls every time and provides a very special window into the natural world. Pick a calm day and off you go!

St Catherine’s Hill, Hampshire

I REMEMBER BOUNDING ABOUT on these chalky slopes in 1966, peering down rabbit holes and hoping to spot a stoat, a superstar species in my Observers Book of British Mammals. One sunny afternoon in 1976, I caught a mazarine blue in my butterfly net (though I can’t prove the record because

I released it and didn’t have a camera). In 1986, I sprinted up the slippery paths chasing kestrels for a film I was making for the BBC, and in 1996 I climbed to the beech hanger on the summit on a stormy winter’s day to try and ameliorate a bout of serious depression. In 2006, I dragged my stepdaughter Megan up to play in the turf maze, and in 2016 I trudged to the summit with my beautiful poodle Scratchy, shortly before he died. Last year, I panted to the top again to honour my father, who had introduced me to this magical place all those years ago.

That gift of a little bit of our planet’s geography has made and saved my life, more a lifemark than a landmark. I love St Catherine’s Hill.

Great North Wood, South London

Once stretching across South London, the ancient Great North Wood today survives as a mosaic of habitats that provide oases for wildlife and green lungs for people. Stepping into its wildest corners, I feel the power of its history dancing through the trees – areminder of its resilience. It is peace to the chaos; fresh air to the smog. Woodpeckers yaffle, firecrests trill, hedgehogs snuffle and bats soar as the moon rises. As a aself-proclaimed GNW fangirl, I implore you to discover its magic.

Canvey Wick, Essex

NESTLING IN THE SOUTH-WEST corner of Canvey Island, Canvey Wick was designated an SSSI in 2005 thanks to the phenomenal variety of invertebrates (1,500 at the last count) that call it home. It’s now one of the best places in Britain for endangered insects, with rarities such as the shrill carder bee, Canvey Island ground beetle and scarce emerald damselfly. In fact, so abundant is the insect life here that Canvey has been compared to a rainforest for species per square metre.

Nineteen hectares of the site are now managed as a nature reserve by Buglife in partnership with the RSPB, on behalf of The Land Trust. What I love most about it is how nature has brazenly reclaimed the land from industry. The site was developed as an oil refinery in the 1970s, but was never used. It differs from the surrounding marshland because the land was stabilised using dredgings from the River Thames, creating the foundations for well-drained, sandy, flower-rich habitats, perfect for invertebrates to colonise. Spring and summer bring a glorious abundance of wildflowers a-buzz with pollinators.

Isles of Scilly, Cornwall

I have the best job in the world: talking about wildlife on the Isles of Scilly. From windswept winters to sunkissed summer days, life on the Atlantic edge is everchanging. I’ve watched humpback whales on Christmas Eve. I’ve been at sea surrounded by shearwaters, skuas and storm petrels with common dolphins bow-riding and sunfish flopping past. Twice a year I’m treated to an array of migrant birds, from hoopoes to bee-eaters. Song thrushes tune up from 3am, house sparrows steal crumbs from cream teas, and shags stand sentry on the rocks. Diversity and abundance, rare and common meet in this land beyond Land’s End.

Briddlesford Woods, Isle of Wight

A FEW MILES SOUTH OF Fishbourne, bordering Wootton Creek and surrounded by farmland, is a wonderful, semi-natural ancient woodland that is at least 400 years old, though some claims date it back to the last Ice Age. With no resident deer population, a walk through Briddlesford is a unique experience. Free from the pressure of browsing, the understorey flourishes. Brambles, honeysuckle, spindle and guelder rose compete with one another, providing a haven for small woodland mammals. Red squirrels and hazel dormice make homes here, alongside rare woodland bats, bank voles and pygmy shrews.

Dotted between the woodland copses is a rich mosaic of parkland, flower-rich meadows and a tidal saltmarsh. Rare flora such as narrow-leaved lungwort thrives alongside green hellebores, butterfly orchids and thin-spiked wood sedge. Sea eagles have recently been released to the area and – it’s claimed – goshawks are making a comeback. Whatever the season, exploring this magnificent wood is always a joy.

Farne Islands, Northumberland

BLACK AND WHITE; Colourful beaks; Known as ‘clowns of the air’; Fun to watch, comical; Birds with character and flair; I love this bird, can you guess what it is? Its name rhymes with ‘nuffin’! A summer visitor to UK shores; The wonderful, adorable… puffin!

After that little ditty, it will come as no surprise that one of my favourite places for wildlife in the UK is a group of islands off the Northumberland coast where, in spring, you are guaranteed to see these quirky little birds. Watching (and photographing) puffins flying in, their beaks crammed with sandeels, soon becomes an obsession.

But puffins are not the only A-listers. The Farnes support a cast of thousands: razorbills, guillemots, shags, cormorants, kittiwakes, terns (which have become notorious for dive-bombing unsuspecting tourists, so a hat is recommended), grey seals and so much more.

A visit to these islands is a memorable attack on the senses. There’s a cacophony of noise from the seabirds and barking seals, it’s a visual smorgasbord, and the pungent smell – areminder of an amazing wild experience – will stay with you long after you’ve sailed home.

Rutland Water, Leicestershire

THE ASTONISHING THING ABOUT Rutland Water is that it’s human-made – areservoir that didn’t exist 50 years ago. Today, its tapestry of lagoons and wetlands are a paradise for anyone who loves being out in nature and is a ‘bad’ birdwatcher like me.

There are not many places where you can try to spot a cuckoo (unsuccessfully) by following its calls, then watch a great-crested grebe attempt to swallow a fish larger than itself (successfully, in the end), before spending a magical evening watching ospreys hunting fish, defending their nests against intruders and taking elaborate, fussy baths. All this while chatting to the volunteers and staff of Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust, who know everything there is to know about the reserve’s wild residents.

In winter, Rutland Water is a hotspot for migratory species, hosting tens of thousands of ducks, geese, swans and even – I’m told – bitterns. It’s an impossible mixture of colourful, joyful, noisy birds.

SHORTS

Hampton Nature Reserve, Peterborough

Jenny Tse-Leon, conservation manager at Froglife

You’d never know there’s a lovely wildlife oasis just 15 minutes from Peterborough town centre. A former brick pit, Hampton Nature Reserve is home to some of our rarest species, and hosts the largest great-crested newt population in Europe. It is a private site but can be visited during volunteer sessions and events run by Froglife. It really is a hidden gem.

Jersey

Will Hall, presenter and photographer

I spent my childhood clambering over this magical island. It may be small, but it has huge ecological importance. Marsh harriers breed here, choughs have been reintroduced, crustaceans thrive in the rockpools and cetaceans regularly pass by. Jersey also has one of the biggest tidal variations on the planet – at low tide, it nearly doubles in size.

Buckfastleigh, Devon

Daniel Hargreaves, bat programme manager at Vincent Wildlife Trust

A self-proclaimed ‘Bat Friendly Community’, this small town hosts the largest colony of greater horseshoe bats in western Europe. Sitting on the banks of the River Mardle on a summer’s evening as 3,000 bats whoosh past to hunt has to be one of the most impressive wild spectacles in the UK.

Rodley Nature Reserve, Leeds

Pam Taylor, trustee of British Dragonfly Society

Nestled between Horsforth and the River Aire, Rodley is a dragonfly and damselfly hotspot on the edge of the city. At least 18 species have been recorded here, with jewels such as banded demoiselle, emperor and four-spotted chaser.

Brasenose Wood, Oxford

WHEN I MOVED TO THIS AREA two years ago, Brasenose Wood – an ancient remnant of Shotover Forest and a 100ha SSSI – was one of the first places I stumbled upon and I’ve been going back ever since.

Like many woodlands, it’s a window to the seasons, with different elements coming to the fore with each passing month. I like to wander, sit and soak it all up, gathering memories like a jay collecting acorns. The trees offer mosses, liverworts and colourful buds in winter, before my attention is drawn to spring’s bluebells. A mellow, soothing light settles during the summer as honeysuckle twines through the hazel copse and treecreepers flit from oak to ash. Then comes the opportunity to collect leaves patterned and coloured by autumn.

This small square of trees is a vital green space for Oxford, separated from rows of houses by the curving ring road and a lovely hay meadow. It stands with the promise of peaceful wanderings and nature treasures.

Dungeness, Kent

THE COLD AIR FILLS MY LUNGS as I breathe in the salty smell of the crashing waves. And yet, if I turn my head in the opposite direction, I can smell heather and fresh, wet grass. RSPB Dungeness is special to me because it is so varied and so vast, a landscape filled with gravel, sand, marshes and memories of jumping hillocks. It’s the third most biodiverse site in the country for insects, and my star species would be the beautiful brown-banded carder bee, which is most frequently seen in June and July, when the land is set alight with wildflowers. If I can tear myself from my beloved bees, I’ll wander over to Burrows Pit, near the visitor centre, to watch seabirds raising their young.

Wimbledon Common, South West London

I live in green, leafy Wimbledon, a suburb far removed in spirit and landscape from the hurlyburly of central London. I’m spoilt for choice where wild spaces are concerned – rural dwellers would be agog at the riches on my doorstep. But Wimbledon Common remains a perennial favourite in all seasons. Covering 460ha of green space, it’s both an SSSI and SAC (Special Area of Conservation), owing to its rich grassland and heathland, and a marvellous green lung for Londoners.

I love walking or cycling to Queensmere Pond, the deepest lake on the common. Shrouded by woods, at noon on a blue-sky day, it’s a tranquil sun-trap with the feel of a far more remote wilderness. I’m always on the lookout for swans, Canada geese and – my favourites – aheron and cormorant, but more patient, keen-eyed birders might encounter a kestrel, sparrowhawk, red kite or even a kingfisher. Once, in a fit of daring, I traipsed alone across the common at dusk, my ears filled with the lightly quavering ‘twoo’ of a tawny owl.

Plenty of mammals live here, too, including badgers and foxes, and let’s not forget the thriving populations of toads, frogs, grass snakes and lizards. Of course, some will argue that the most sought-after sighting on Wimbledon Common is the legendary litter-picking Womble, but that’s another story…

SHORTS

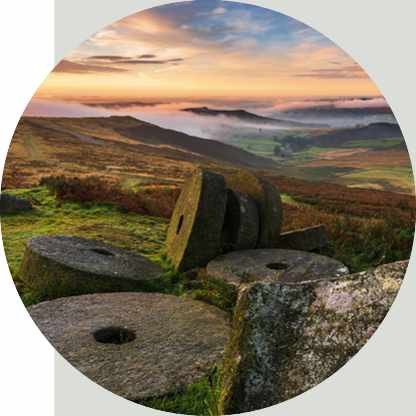

Stanage Edge, Peak District National Park

Ben Hall, wildlife photographer

I’ve lived on the edge of the Peak District my whole life and know the area well, particularly the Stanage Edge escarpment.

I’ve had some unforgettable wildlife encounters here, particularly with red grouse. My favourite time of year is August, when blooming heather swathes the moors in pink and purple hues. I could never tire of Stanage Edge.

Haugh Woods, Hereford

Savita Willmott, CEO of The Natural History Consortium

This isn’t my local patch, rather one I adopt when visiting family, but it is fast becoming a favourite place for happy times in the wild. It’s nationally important for butterflies and moths, home to more than 600 species, including the rare pearlbordered fritillary.

Attenborough Reserve, Nottingham

Jack Perks, underwater photographer

I’ve been visiting this Wildlife Trust reserve for 15 years and it still surprises me. As well as 30 species of fish, highlights include sand martens, kingfishers, otters and, in winter, bitterns and flocks of murmurating starlings.

Spean Bridge, Highlands

Fay Vass, CEO of British Hedgehog Preservation Society

I always think fondly of Spean as it’s here I saw my first pine marten, somersaulting out of a skip. The area is also a Scottish wildcat stronghold and the nights are alive with owl calls. You can even see the Northern Lights from the Commando Memorial statue, which is still on my list – I must return!

Foxley Wood, Norfolk

FOXLEY WOOD IS NOT A FAMOUS place, and its low dome of trees is not particularly conspicuous in the flatlands of central Norfolk. But there’s magic within.

I grew up 5km or so from Foxley. It was our local wood, and we visited in autumn for fungi and falling leaves, in spring for bluebells, and in summer – in vain – for the mysterious purple emperor butterfly.

My childhood marked the nadir of Foxley. Norfolk’s largest ancient woodland was recorded in the Domesday Book, but was nearly destroyed in the 1960s when half its ancient oaks and coppice were felled, burned and sprayed so a conifer plantation could rise in its place. Rare woodland flowers and invertebrates were crowded out and the purple emperor went extinct in the county.

Foxley’s recovery began when Norfolk Wildlife Trust bought it just over 30 years ago. The conifers were sold off as Christmas trees and the site allowed to regenerate. The transformation today is astonishing. It’s difficult to tell ancient woodland from modern in the tumult of self-sown gelder rose, dogwood, sallow, hazel, blackthorn and field maple. Its rides ring with birdsong in spring and thrum with dragonflies in summer, while raptors dash overhead.

There’s restored coppice, huge vines of honeysuckle and, most remarkable of all, after nearly five decades of extinction, the purple emperor has returned, flashing iridescent purple as it glides through the midsummer trees.

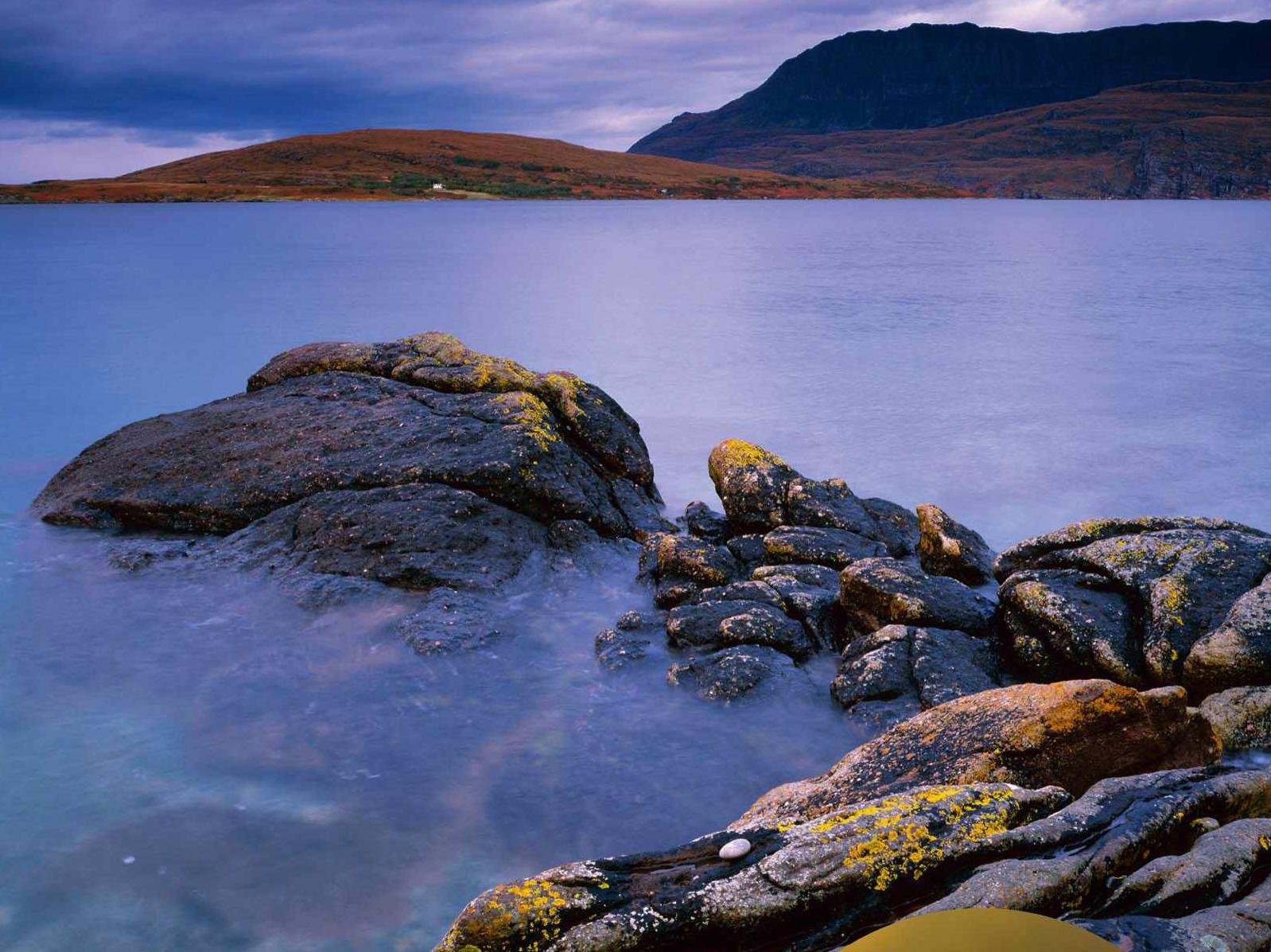

Isle Martin, Ross and Cromarty

I LOOKED THROUGH THE stunningly clear water at the seabed 15m below. A dogfish lazily tail-swiped over the sand, disturbing a flounder who undulated for cover in the nearby kelp. I drifted along steep-sided underwater gullies, their walls orange and yellow with cup coral. Gobies, blennies and squat lobsters peered out from the crevices; urchins grazed the rocks.

That was back in 1972, and the vibrant colours, dappled seabed and feeling of floating in space were all so vivid they felt unreal. I’d only made 60 or so dives up to that point, but when I surfaced I knew that the sea and I were destined to have a deeply personal relationship.

Isle Martin lies about 6km north of Ullapool. April to June brings breeding birds; as summer rolls on, twites, redpolls and siskins fly around the old houses while sea eagles soar overhead. To the west of the island, Annat Bay is visited by grey and harbour seals, common dolphins, minke whales and even the occasional humpback. It’s a lovely wee island, a microcosm of all that’s wonderful about Scotland’s west coast.

Barton Hills, Bedfordshire

A SHORT HOP FROM LUTON, AT the northernmost tip of the Chilterns, lies the Barton Hills National Nature Reserve – aplace I adore exploring. Walking in nature nourishes my mind and body, and this is the perfect spot. It teems with butterflies and chalk downland wildflowers, including the stunning pasqueflower, and is the ideal place to marvel at one of our most majestic birds of prey: the red kite.

Driven to extinction in England in the late 1800s, the sight of a swooping, reeling red kite is testament to one of the most successful reintroduction projects ever undertaken. I always feel a sense of wonder when these magnificent birds soar overhead.

Isle of Mull, Inner Hebrides

UNTIL THE AGE OF 17, my experience of the world’s wildlife was limited to whatever was local. However, I was raised on Mull, and this island’s wild offerings are nothing short of magnificent.

I’ve spent 30 years in the wilds of the world, from the high Arctic to the tip of South America. I’ve have had more than my fair share of encounters with the furred and the feathered, with creepers and crawlers, with animals that scamper and those that sprint, but some of my best have been on the island of my youth.

Intimate encounters on frosty shorelines with a family of otters; golden eagles sky-dancing in spring skies; the bewildering bounty of summer: minke whales, dolphins, puffins, razorbills, guillemots, Manx shearwaters. All of this exists against a backdrop of unrivalled beauty. There are towering mountains, sheltered bays, white-sand beaches, caves, woodlands, moorland, sparkling waters and rugged coastal cliffs.

I’ve lived a life on the road, following tracks and trails in some of the world’s most stunning places, but one path always leads me back to the most special place of all. If you want to know what paradise looks like, it is this island full of Hebridean magic off the west coast of Scotland.

Brockholes, Lancashire

A VAST QUARRY IN ITS FORMER life, Brockholes is now a thriving 100ha nature reserve and wild haven right next to the M6 and River Ribble, managed by the Lancashire Wildlife Trust. It’s a wonderful place to connect with nature, and I particularly enjoy reading all the latest sightings in the bird hide. Ospreys are seen relatively often, though I haven’t managed to spot one yet. I have, however, seen kestrels, herons, deer and my first ever weasel (a lucky encounter) at Brockholes.

I joined a guided walk around the reserve recently, through its ancient woods and around its reed-fringed lakes. The guide was incredibly knowledgeable and passionate and it was great to learn how the reserve is managed for wildlife. We have so many fascinating species in the UK – you see a lot more of them once you start taking notice.

Wormwood Scrubs, West London

I am in love with a place so innocuous that, when I first stumbled across it some 25 years ago and claimed it as my nirvana, my birdy friends thought I had lost my mind. That place is Wormwood Scrubs, a 77ha park that adjoins the prison of the same name and was featured lyrically in The Jam’s Down at the Tube Station at Midnight.

Consisting of playing fields, a small area of grassland and limited woodland, it doesn’t look like it would attract wildlife. But after my inaugural visit, I realised its potential for birds and became a regular visitor. I have seen more than 150 species here, including regional scarcities such as meadow pipits and short-eared owls. It was here that I coined the phrase ‘look up’. And it is here that the ring ouzel, my favourite bird, occurs annually on migration – just, it seems, to delight me.

Winter Hill, Greater Manchester

WHEN I CLIMB TO THE SUMMIT OF Winter Hill, which dominates the 688ha Smithills Estate, I feel like I’m on top of the world. I’m level with the clouds hanging in the blue sky, and looking into the horizon I can see the rooftops of my home town of Manchester.

The site is managed by the Woodland Trust and is being restored and revitalised with tree-planting galore – thousands of saplings have gone into the ground here. Wildlife to look out for includes deer, common lizards and cuckoos, while walking through woodlands replete with wonderful fungi, trees and plants.

I began exploring Smithills a few weeks after a serious fall that shattered my right wrist. Getting back out in nature walking again was brilliant for my recovery, and I now lead ‘walkshops’ focused on the ameliorative effect of the natural world on our physical and mental health. I’ll never forget seeing two glorious lapwings swirling in the skies one afternoon, singing their hearts out above the wild west Pennine moors. It was a sight and sound that made my heart soar.

Glen Tanar, Cairngorms National Park

GLEN TANAR IS A PHENOMENAL part of Scotland. It’s a remnant of the ancient Caledonian pine forest, the green belt that once ran the breadth of the Arctic Circle, and it shelters some of the oldest, largest pine trees in the UK. These trees are incredible – they’re known as granny pines and have been standing for hundreds of years. The trees you see in modern pine plantations tend to be the same age (20-30 years old); those in Glen Tanar range from the young to the old to the absolutely ancient.

The bird life here is astounding, too – we’re talking apex avian predators. There are hen harriers, golden eagles, white-tailed eagles, goshawks and ospreys, plus the rare and lovely capercaillie and the Scottish crossbill, Britain’s only endemic bird.

A few years ago, I filmed golden eagles breeding in Glen Tanar for a David Attenborough film. These raptors don’t usually nest in trees, preferring remote cliffs, but the massive, gnarly, ancient pines here can easily support the bulk of a one-tonne eyrie. Watching the chicks develop and grow that spring is one of my all-time favourite memories of this inspiring, beautiful place.

Sherwood Forest, Nottingham

THIS HISTORIC FOREST, AN RSPB reserve, is just half an hour from where I live. With more than 1,000 ancient oak trees and beautiful lowland heath, it traces a direct line back to the royal hunting ‘forest’ it once was. At its heart sits the Major Oak, a popular colossus said to have once housed Robin Hood.

In spring, I’m drawn to Sherwood for the sound of woodpeckers and the ethereal sight of a roding woodcock. In summer, it’s for the mysterious churring nightjars and the joyful woodlarks. Sometimes it’s for the high-pitched contact calls of tiny goldcrests flitting through the canopy, and occasionally even the elusive sight of a goshawk. But at any time of the year it offers tranquillity (once you’ve escaped the jousting!) and the chance to immerse yourself in a greener, wilder space. Sherwood is where I recharge my batteries and breathe more deeply – just for a moment.

SHORTS

New Quay, Ceredigion

Chris Vick, director of strategic development at WDC

I’ve seen dolphins all over the world but my best sightings have been at New Quay. An arching back, a tell-tale whoosh of breath, an acrobatic breach, a fast, silver body more powerful than you imagine. As well as the magic of dolphins, there’s a magic of place here – this is Dylan Thomas country. Visit out of season, look out into the night and breathe in the “sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack fishingboat-bobbing sea”.

Ben Shieldaig, Highlands

Oliver Moore, advisor at Plantlife

I have spent many captivating hours on these looming, steep slopes, mapping and surveying the vegetation. I’ve studied everything from sparkling signal moss and prickly featherwort in the birch woodlands to dwarf junipers on the windswept, wet heath of the summit ridge. Scottish rainforest doesn’t come much finer than Ben Shieldaig.

Teesside, Yorkshire

Steph Wray, chair of The Mammal Society

When I was growing up on Teesside in the 1980s, the tidal Tees was the UK’s most polluted river. Today, it’s very different. Grey seals bob, cormorants dry their wings, skuas and terns fly overhead and, at the transporter bridge, otters feast on salmon. This burgeoning of life in what was a poisoned wasteland shows how we can restore nature.

Rodborough Common, Gloucestershire

Matt Swaine, editor of BBC Wildlife (2013-2015)

Patrick Barkham’s The Butterfly Isles inspired me to seek out all 59 native species, but on two wheels. Rides so far include to Dorset for silver-studded blues and Devon for clouded yellows, but nothing beats the mix at Rodborough. It is my perfect day out.

Ynys-hir, Ceredigion

OF ALL THE PLACES I VISITED IN my 10 years co-presenting Springwatch, RSPB Ynys-hir is the most memorable. The scenery is spectacular, with gnarled green oakwoods and the yellow sands of the Dyfi Estuary against a majestic backdrop of curving mountains. I walked in every morning and felt like I was plunging into a world teeming with wildlife.

There can’t be many places with such a mix of habitats and diversity of wildlife, including, to name a few stars, otters, stoats, kingfishers, redstarts, water rails, hen harriers and merlin, as well as a plethora of insects, reptiles and amphibians. I remember one mesmerising day filming grass snakes in a compost heap using a heat-sensitive camera – we could see glowing holes where the snakes moved in and out, warmed by the compost. We also filmed a common sandpiper nest beside the railway line – the incubating adult would jump off as the train thundered past, then scamper back.

There are, apparently, lesser-spotted woodpeckers at Ynys-hir. I’m tempted to return to see if I can ‘break my duck’. As a keen motorcyclist, the ride through Wales would be the icing on the cake.

Hermaness, Unst, Shetland Islands

IT IS THE RAW, UNTAMED NATURE of the UK’s most northerly point that most appeals to me. To the west is 5,000km of nothing but unbroken ocean, from where ferocious storms barrel in towards the jagged coastline.

The cliffs of this National Nature Reserve are both perilous and precipitous but teem with bird life in the summer. The vast and expanding gannet colony is visually the most dramatic, but then so too are the grassy clifftops when filled with the comical presence of puffins. Just inland lies the skua colony, and though these birds have been badly hit by the recent outbreak of avian flu, they remain an ever-present malevolence.

Summer brings a glut of species, including passing orcas, but it is autumn that most stimulates the senses.

The ocean becomes a cauldron of unbridled ferocity, with gannets soaring effortlessly and imperiously over the raging tumult. Hermaness gets under your skin like no other place in the UK.

Andy Parkinson, wildlife photographer

Exmoor National Park, Devon and Somerset

Growing up in North Devon, it was on the moors that my love of nature was born. Up the steep hills and cliffs from the sea, a rugged landscape as ancient as anything England has to offer unfolds across rolling hills, disappearing into impassable valleys.

Ancient forests, rich in lichens, mosses and ferns, give way to heathland and peat bogs. Red deer have lived on the moors since prehistoric times. Birds of prey soar overhead – buzzards, peregrines, sometimes merlins – and the heather is home to countless insects.

It’s not uncommon while walking on the moors to encounter a small herd of Exmoor ponies – ‘wild horses’ to the locals – whose dark backs and light bellies brought to my young mind animals painted on Stone Age cave walls. I remember once waking from a doze in a valley to find these horses completely ignoring me at very close quarters.

As a child, day trips up onto the moors were like stepping back in time. Human settlements here date to the Mesolithic, and some areas still feel largely unchanged since then. It’s a wonderful wilderness.

Wallasea Island, Essex

LESS THAN TWO HOURS FROM our base in London, RSPB Wallasea is the perfect spot for walks with Flock Together, our birdwatching collective for people of colour. It was here that we saw our first owl – abarn owl, hunting like a ghost in the golden dawn light. Formerly arable farmland, the 740ha reserve is now a landscape of saltmarsh, mudflats, lagoons and grazing marsh. In summer, terns dive for fish while marsh harriers seek small mammals from the sky. Autumn brings passage birds such as ringed plovers, dunlins and greenshanks, and flocks of wildfowl such as teal, wigeon and brent geese arrive for the winter. It’s an ideal spot for experienced and novice birdwatchers alike – we love Wallasea!

London Wetland Centre, South London

THIS WONDERFUL SPOT, WHICH I first visited in 2018 for the launch of the government’s 25-year Environment Plan, is creating new nature memories for me. Walking in on that cold, damp January day, my eyes were opened to a wetland in the heart of London, a place for wildlife to thrive and a deeply meditative place for people to explore. Once four reservoirs, it has been transformed into a 40ha wetland and provides a key stopping-off point for migratory birds. The view from the Peacock Tower is stunning and a great vantage point for spectacular displays, such as courting great-crested grebes. Many species have made a home here, some of which are found nowhere else in the capital. Only recently did I catch sight of a green sandpiper while on a quest to see my first bittern. No success on that visit; maybe I’ll be luckier next time.

Polzeath to Holywell Bay, North Cornwall

THE NORTH CORNWALL COAST is famous for its spectacular scenery, with high, rugged cliffs and white-sand beaches. I moved here 20 years ago and there is nowhere I’d rather be. One stretch that is absolutely exquisite for wildlife runs for roughly 50km from Polzeath to Holywell Bay. The rocky outcrops and headlands are frequented by the likes of peregrines, kestrels and barn owls, and are brimming with rabbit warrens, badger setts and fox dens. Spring and summer bring bustling seabird colonies filled with the chatter of fulmars, guillemots and razorbills, while common dolphins slice through the seas. If you need a wildlife fix, this part of Cornwall has so much to offer. There is nowhere in the UK quite like it.

Now, over to you…

WE’VE HEARD FROM the experts, now it’s your turn. We want to find out which of these 60 places is the nation’s favourite – and we need your votes! Have your say at discoverwildlife.com/60faves and we’ll reveal the winner in a future issue.