MIRACLE MEADOWS

Ibiza’s seagrass is a wonder plant and one man has made it his mission to protect it

To learn more about the world of plants catch up with The Green Planet

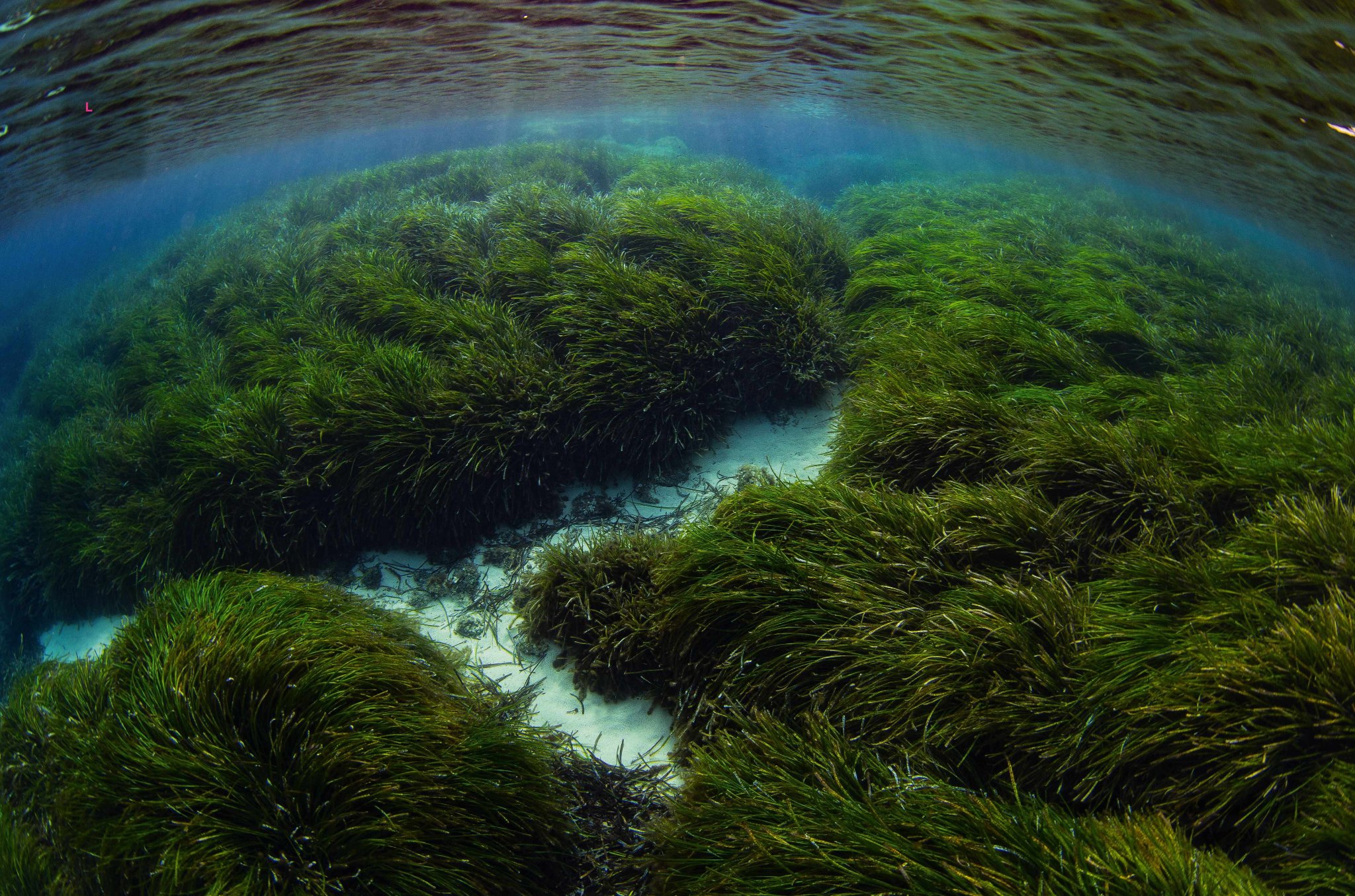

WITHOUT DROPPING ANCHOR, THE DIVE boat drifts slowly to a stop in some of the clearest water in the Mediterranean. The secret of this perfect turquoise sea, off the Balearic island of Formentera, lives just below its surface. I roll over the side with a splash and there it is all around me: uniform pale green mops swaying in the gentle current. It is Posidonia oceanica; a seagrass found only here in the Mediterranean.

Named after the Greek sea deity, Posidonia (or Neptune grass in honour of its Roman counterpart) is a subaquatic superplant. It cleans water, fights climate change and generates oxygen. The 15km or so sea floor separating Formentera from its noisy, party-island neighbour Ibiza is carpeted with the stuff. This entire submarine savannah is one huge, self-cloning organism that, at about 100,000 years old, is more ancient than both Poseidon and Neptune. But it is vanishing at an alarming rate.

Punta de Sa Pedrera is a rocky outcrop a short RIB ride from Formentera’s La Savina harbour. Its secluded coves are dotted with local fishers’ huts and painted wooden boats. Once a Roman fishing settlement, divers still find pottery fragments on the seabed here. Back in the 1960s, hammerhead sharks were caught daily in this shallow bay. Today, they are almost extinct. But for now at least, the seagrass remains alive and well. Sea bream and goldline swim through its waving, tapelike leaves, while sunlight catches the silvery flank of a well-fed sea bass patrolling above.

A naturally photogenic wildlife haven, the BBC series The Green Planet filmed here, describing Posidonia as “one of the most important plants on Earth”.

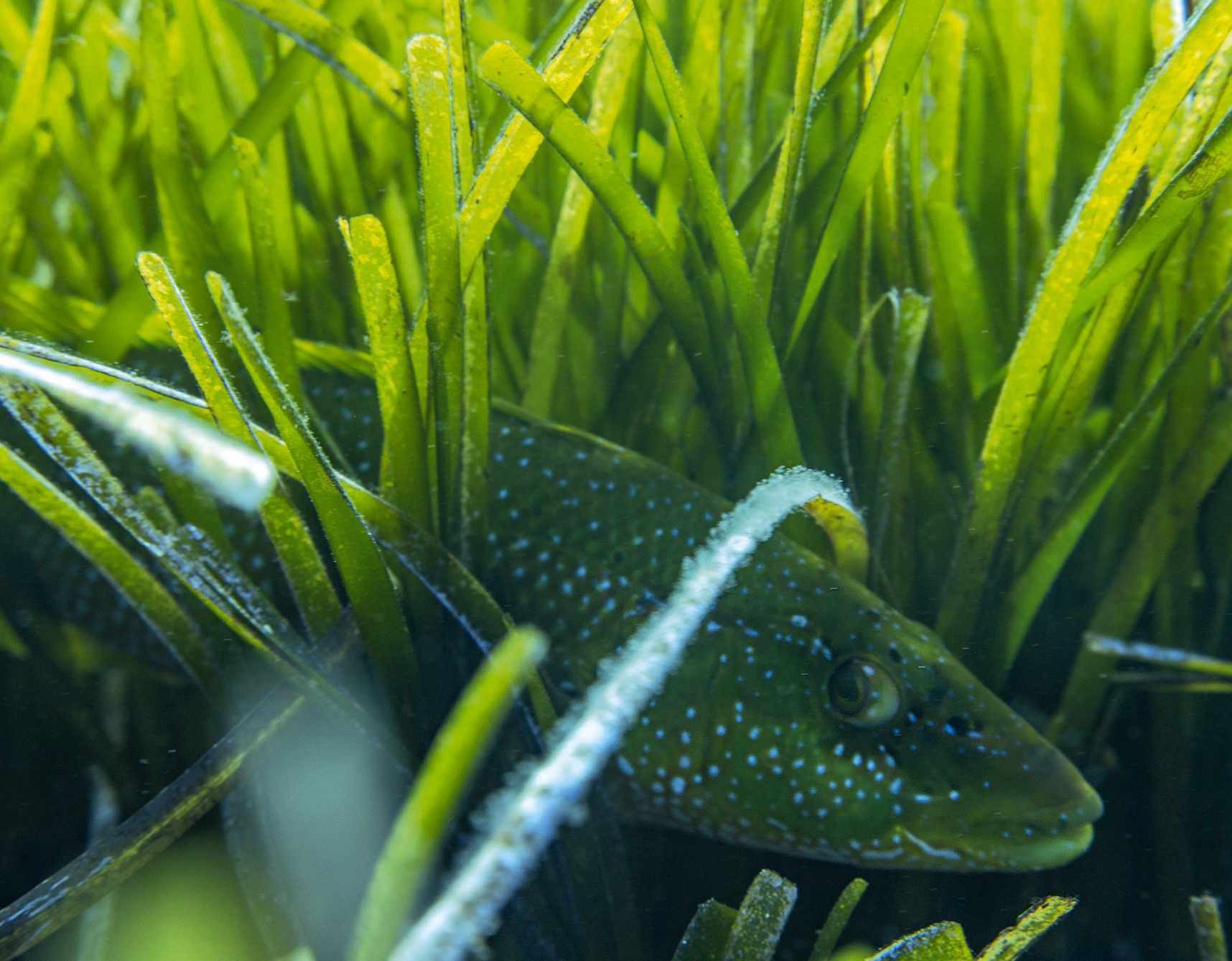

A POSIDONIA MEADOW is an ecosystem of incredible biodiversity. As a nursery for marine life, it provides food, protection and a place to mate and lay eggs. More than 400 plant species and 1,000 animal species call it home. Residents include turtles, and fish such as rainbow wrasse, grouper, pipefish, scorpion fish and trigger fish.

Its undulating emerald foliage is a habitat for fragile species such as the Pinna nobilis, a clam that can grow to more than a metre in size, and which is recovering from a 2016 disease outbreak that wiped out 99 per cent of the population in Spain. At the opposite end of the scale, the rare, jewel-like, long-snouted seahorse relies on Posidonia for camouflage and protection, wrapping its tail around the narrow leaves as it grazes on plankton passing in the current.

Not to be confused with seaweed, seagrasses are the only flowering plants able to live in saltwater. There are just 72 of these so-called marine angiosperm species around the world (see box right). Posidonia can also reproduce asexually by generating exact clones of itself, making it a potentially immortal plant.

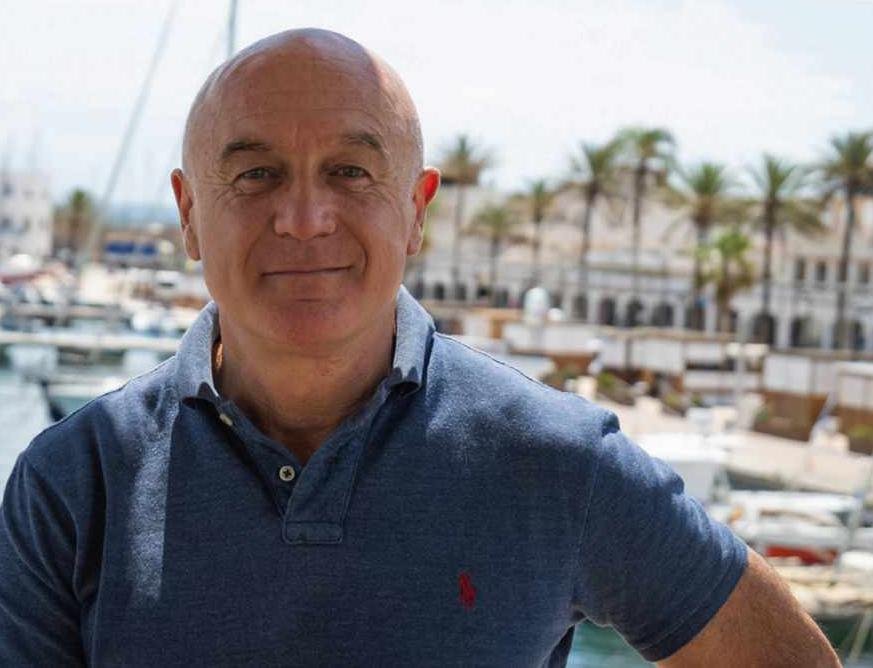

“It looks exactly like a land plant because it comes from a land plant that continued evolving and went back to the ocean,” says Manu San Félix, a dive instructor and underwater film-maker who has dedicated 30 years of his life to protecting Posidonia.

“It’s like the marine mammals that descended from land animals and re-conquered the aquatic world.”

“Posidonia oceanica absorbs carbon dioxide up to 35 times faster than a tropical forest”

When he arrived here in 1992 as a young marine biologist, the rocky bays of Punta de Sa Pedrera gave Manu his first, life-changing glimpse of the island’s seagrass meadows. “I jumped in and I was blown away!” he recalls. “Oh my God! I was in love!” Struck by their beauty, Manu immersed himself in every sense. He became a diving machine, constantly roaming the Posidonia beds, photographing their marine life and teasing apart the long leaves to observe the hidden world within. “This is a tiny jungle,” he says. “You have starfish, sponges, anemones, nudibranchs, bryozoans, molluscs. ManyspeciesdependonPosidoniatoliveandreproduce.”

He speaks passionately, occasionally thumping the table for emphasis, rattling off Posidonia facts and figures from memory. A single square metre generates up to 20 litres of oxygen a day, he explains – as much as a hectare of pristine Amazon rainforest. “If you do a quick calculation, the meadow between Ibiza and Formentera is providing the oxygen for the population of both islands to breathe,” he says. “This service is provided to us for free. What more reason do you need to protect this plant?”

GIFTS THAT KEEP ON GIVING, these ‘lungs of the Mediterranean’ are a crucial natural defence against climate change. Globally, seagrass meadows are significant carbon sinks and Posidonia oceanica is the most effective species, absorbing carbon dioxide up to 35 times faster than a tropical forest. An estimated half of the carbon buried in marine sediments around the world is trapped in the tangled roots and rhizomes (known as the matte) of seagrasses.

Dead fibres and roots also trap plastic pollution in golf ball-sized clumps known as ‘Neptune Balls’ that eventually wash up on the shore. A recent study found they bundle up as much as 900 million pieces of plastic from the Mediterranean every year. Posidonia protects the coast from erosion too. The meadows act as a buffer, slowing the power of waves, while the plant’s dead leaves accumulate on beaches in masses called banquettes that shield the shoreline from winter storms. In the past, this material was used as roof insulation for Ibicencan houses and as fertiliser for the island’s potato fields.

In return for all these ecosystem services, all Posidonia needs is clean water and stable temperatures. Yet humans are failing on both of those fronts. Today’s Mediterranean is widely agreed to be the most polluted sea in the world, a dumping ground for 650 million tons of sewage and 500 shipping containers worth of plastic every year. And climate change is pushing sea temperatures to dangerous levels. At 28˚C, Posidonia stops growing and starts to die. The waters around Ibiza and Formentera regularly reach 29˚C during the summer.

Manu has been ringing the alarm bell for decades. His report on the Posidonia meadows paved the way for their designation as the Mediterranean’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. That same year, the 13,000ha Es Freus Marine Reserve was created between the southernmost tip of Ibiza and north-west Formentera.

OTHER SEAGRASS PROJECTS

Seeds for Snapper

SOUTH AUSTRALIA

Eleven species of seagrass grow in the waters off South Australia, covering an area of nearly 1,000km2. The Seeds for Snapper initiative, launched in 2020 by fishing conservation charity OzFish, involves collecting seeds on the beach, which are used to restore seagrass meadows. The hope is to re-establish about 10ha of seagrass off the Adelaide coast, which will provide habitat for fish such as snappers (hence the name), calamari and whiting.

Danish divers

DENMARK

Seagrass once covered the seabed at Vejle Fjord, on Jutland’s east coast, but 90 percent of the seagrass meadows here have been destroyed by wastewater pollution in the past 30 years. The University of Southern Denmark has enlisted volunteer divers to hand-plant eelgrass seeds on the ocean floor.

Project Seagrass

UK

The UK has four types of seagrass in its waters, including two Zostera species, commonly known as eelgrass. Nearly 40 per cent of meadows have been lost since the 1980s. Project Seagrass was founded in 2013 and its biggest restoration project to date is in Dale, Pembrokeshire, where more than one million seeds were planted across 2ha in 2019 and 2020. The site is now being monitored, and will guide other restoration efforts in the UK.

BUT WITH IBIZA’S TOURIST industry booming, Posidonia is under growing threat from an explosion in boat traffic, from pleasure cruisers and local ferries to mega yachts and colossal cruise ships. “Fifty years ago it was one or two boats, but now we have thousands every day,” says Manu. “I could see the damage caused by anchors and chains, so I decided to film it.”

Manu sought out the biggest boat with the heaviest anchor and photographed its drifting chain destroying a Posidonia bed in just eight hours. The resulting video provoked national outrage. “Many people cried,” he recalls. “The Spanish newspapers were ringing me every day and I was under a lot of pressure from the boating industry. We depend on tourism and we need boats to come. This is not a battle against boats, but to do things with common sense.”

Manu followed up with a seabed survey between 2008 and 2012, which, together with previous studies, revealed plants being lost at an alarming rate: a third of the western Mediterranean’s meadows gone in a few decades. “I was shocked,” he says. “If we continue like this, boats will wipe out all the Posidonia in this area within ten years.”

Ibiza’s longest-established environmental organisation, GEN-GOB, has been monitoring the impact of anchoring and declining water quality on Posidonia meadows for the past three years. “The seagrass meadows in the Balearics are like coral reefs in the tropics,” says marine area specialist Xisco Sobrado. “Our divers check density, cover and the percentage of meadow that has been lost or is already dead. In areas with anchoring you can lose 30 per cent in three or four years; in some places as much as 50 per cent. It’s a big emergency.”

“In areas of anchoring you can lose 30 per cent in three or four years; in some places as much as 50 per cent”

XISCO SOBRADO, MARINE AREA SPECIALIST

REPLANTING IS POSSIBLE BUT is not a viable short-term solution: a square metre patch of seagrass killed in a few hours by a single anchor can take a century to regrow. “If we put a plant in the middle of a 15m diameter circle of bare sand, it will take 250 years to cover that circle,” explains Manu. “The challenge is to make society change – this is always going to be difficult.”

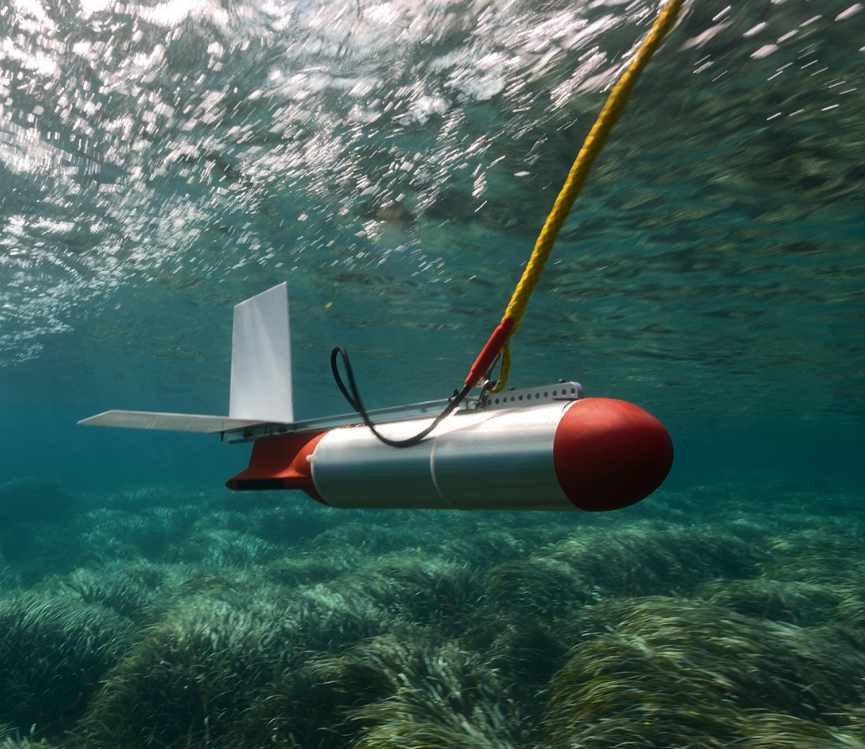

Fortunately, action has been forthcoming. In 2018, the Balearics’ government passed a decree making it illegal for boats to anchor over Posidonia. Since then, using underwater cartography technology known as side-scan sonar, Manu and his team have developed a free app to help skippers avoid meadows and locate safe anchoring areas around Formentera. The efforts to preserve Ibiza’s Posidonia are part of an ambition to recover the whole Mediterranean ecosytem by 2030.

Education also plays into this, and local skippers Mirko Abbruzzese and Diego de le Vina have developed a government-approved responsible sailing course aimed at the charter industry. “Crews have to understand the importance of biodiversity,” says Mirko. “Once they understand, they value; once they value, they will act.” Captains are taught environmental best practice at sea, from protecting Posidonia to cutting marine pollution. “We hope this course will one day be mandatory for anyone navigating our natural reserves.”

The Med’s problems are far from unique, of course. The effects of overfishing, pollution and climate change are visible in seas worldwide. “But you see it here first,” says Manu. “The Mediterranean is a small and almost enclosed sea. Imagine being in a cinema and turning off the air conditioning. The only way to refresh that air is to open a door – that door is the Strait of Gibraltar.”

His hope is that lessons learned around Formentera can be applied to protect seas and oceans globally. ‘‘We have an opportunity because we know the solutions. We can test mechanisms to recover fishing, improve water quality and reintroduce species,” he says. “And if we do it the right way, we’ll see the return faster than in the ocean because this is smaller.”

Restoring the world’s most damaged seas won’t be easy. But, properly looked after, Posidonia – a forever plant named after ancient sea gods – will be a powerful ally.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Freelance journalist and film-maker Richard Fleury has travelled the world reporting on everything from marine life to motor racing. His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including The Times, the Guardian and Wired.