PORTFOLIO

Gulls on film

Urban gulls are considered a pest in Dutch cities, but these intelligent birds are simply responding to habitat stress

Don’t mind if I do (above)

The lesser black-backed gulls and herring gulls (juvenile pictured) of Amsterdam know to expect breakfast when residents put their bin bags out in the morning, says David Hup, who spent a year photographing the birds in his native Netherlands: “They tear the bags apart and spread the rubbish all over the street.”

Grub’s up

When bin lorries arrive at this waste processing centre in Amsterdam, huge flocks of gulls fly down from neighbouring rooftops to ransack the newly arrived rubbish. “It was total mayhem with gulls searching for leftovers,” David says.

Feathered friends

This child was playing with a herring gull, offering it a chip, but not all human-gull interactions in Dutch cities are so friendly. “The gulls are really territorial and aggressive when they have chicks,” says David, citing the experience of a friend who was attacked by nesting gulls each time he left the house.

What you looking at?

David was motivated to photograph urban gulls by a curiosity about what draws the birds to cities in the first place. He learnt that they’ve made the move following the destruction of their coastal breeding grounds and an increase in predation.

Seaside sounds

David grew up in Amsterdam but spent childhood weekends at the seaside. As a result, “the sight and sound of gulls has always reminded me of spare time and relaxation,” he says. “Then I discovered that a lot of people think they’re super annoying! So I decided to document what’s happening with gulls in city environments.”

Guest of honour

Hague resident Eloise Brouwer ran an Instagram account for ‘Dodo the Seagull’, one of a family of herring gulls that regularly visited her balcony to be fed. “She made a particular noise and they would arrive,” David says. “They really responded to her.” Eloise has since moved house – she’s told David how much she misses her gull friends.

In you go

David shadowed seabird biologist Roland-Jan Buijs as he studied urban gulls in Dutch cities. He tracks their weight by carefully sliding them into a ‘weighing tube’ for a couple of seconds so they don’t hurt themselves while flapping.

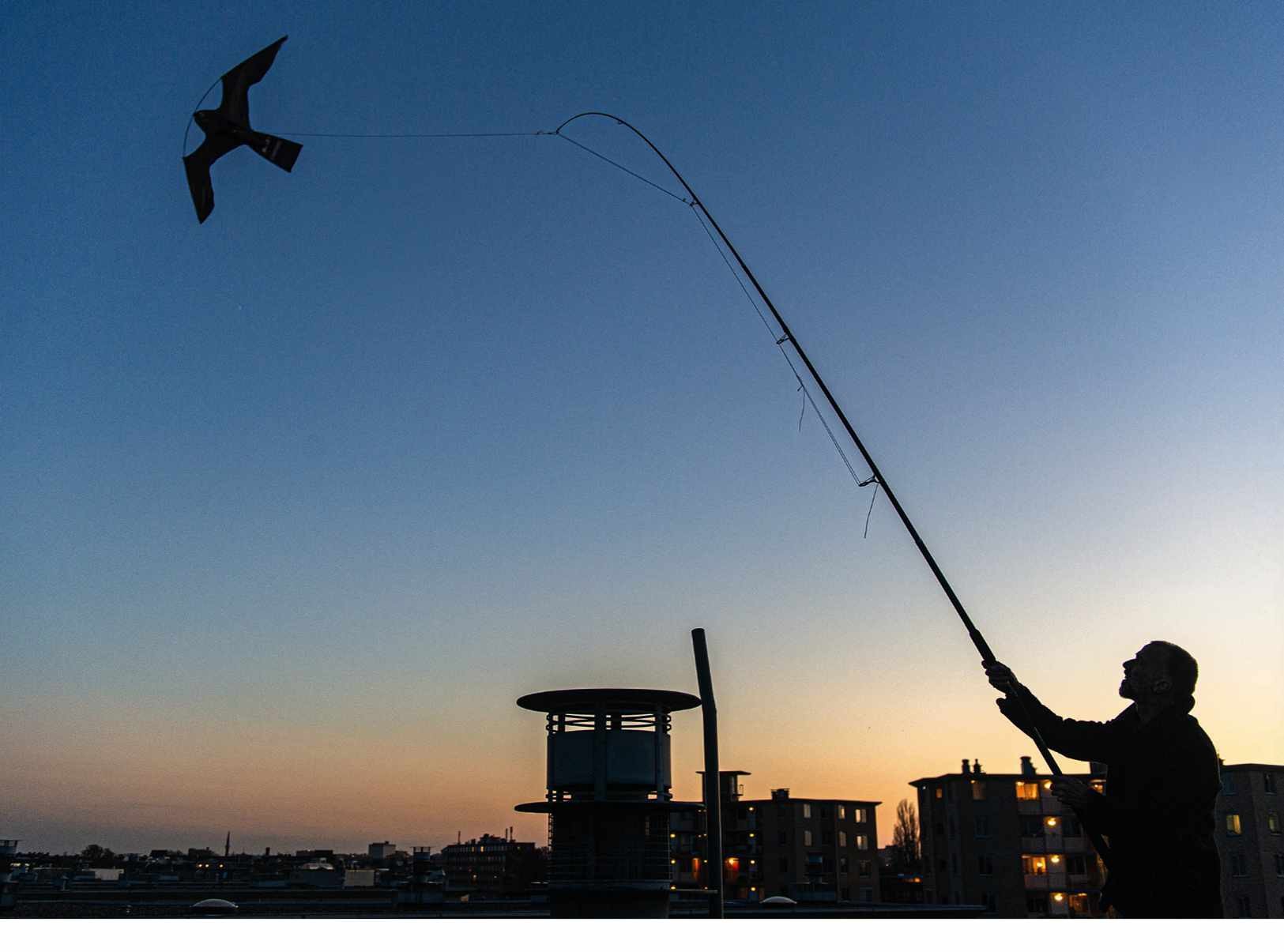

Scare tactics

City dwellers use kites, like this one being installed by David’s father Bert, to try to deter gulls from nesting on their roofs. They object to the noise of the chicks calling for food, the mess that comes with the birds defecating all over the roof and nearby cars, and the trauma of seeing almost-fledged chicks that have fallen from the nest.

Home sweet home

David visited rooftop nests with Roland-Jan as part of his monitoring work, as well as with teams licensed to remove gull eggs in an attempt to curb population growth. They are replaced with plastic dummy eggs to dissuade the gulls from simply laying more. He loved the experience: “You are in a totally different world because it’s almost like a desert up there. It’s like you’re in a gull town.”

Kicking up a fuss

Roland-Jan’s team removes gull chicks (these are just a couple of weeks old) from their nests to measure and ring them, before returning them to the bosom of their family. By gathering data on both eggs and the chicks that hatch from them, Roland-Jan hopes to gain a better understanding of the gulls’ breeding success in urban environments.

New arrival

The teams tasked with removing gull eggs and replacing them with plastic dummy eggs are not permitted to touch chicks. Egg collecting is only licensed in one municipality currently: Alkmaar. It is a crime to interfere with gull nests without a licence.

A bird in the hand

Roland-Jan has been ringing gulls, such as this lesser black-backed individual, since he was 18 years old. What began as a hobby turned into a career – he researches gull populations all over the Netherlands, advising companies and municipalities on how to deal with ‘nuisance’ gulls.

Bright ideas

The most effective way of stopping gulls from nesting on rooftops is installing nets. But as that only moves the problem elsewhere, Roland-Jan’s strategy is to identify more suitable environments, where gull noise and mess are less of an issue (in industrial areas, for example), and attempt to make those sites more attractive for nesting birds.

Measuring up

Roland-Jan’s research assistant Naomi Huig carefully measures gull eggs; these figures will be cross-referenced with data about the hatched chicks later on. Lesser black-backed and herring gulls typically incubate a clutch of two to four eggs for around 28-30 days, with both parents involved in incubating the eggs. Chicks fledge after four to six weeks.

Right royal mess

This statue of King William II of the Netherlands stands outside the Dutch parliament building in The Hague, right next to one of the city’s ubiquitous herring stalls. David reports that it’s common for gulls (here, a herring gull) to wait nearby before stealing food from unsuspecting customers. “There’s always a gull sitting on top,” he says.

A safe space

David became more sympathetic towards urban gulls over the course of the project and hopes others will rethink their negative attitudes to the birds, too: “I ask people, ‘Why do you think they’re coming here?’ It’s not like it’s a free choice. It’s not going well for the gulls and they’re just searching for a safe space in cities.”

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

David Hup is a documentary photographer fascinated by the relationship between people and nature. He uses photography to raise awareness about our impact on nature with the goal of creating a sustainable foundation for coexistence. See more of his work at davidhup.com.