Mike Dilger’s wildlife spectacles

The broadcaster, naturalist and tour guide shares the most breathtaking seasonal events in Britain

The Boxer

BOXING BROWN HARES

Bag a ringside seat to see battling brown hares during their mating season

TO THOSE WITH A NATURAL HISTORY bent, the month of March is synonymous with one spectacle above any other – that of brown hares duking it out. Celebrated throughout the ages, it was undoubtedly this very behaviour that inspired Lewis Carroll’s March Hare character in Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland.

Despite the brown hare being easily the more familiar of our two hare species, it is only the lesser-known mountain hare that is in fact native to Britain. Originally emanating from the grassy plains of Asia, brown hares are believed to have been introduced either during, or before, Roman times. Favouring open habitat, the hare found such an abundance of farmland and grassland in Britain that the only areas seemingly avoided by this inveterate nibbler were our mountains and moorlands – niches that may well have already been filled by the brown hare’s montane cousin.

Adult brown hares can be distinguished from our only other lagomorph, the rabbit, by their longer limbs, larger heads and longer, black-tipped ears. When running, their distinctive tail is kept down, revealing a black upper surface as they sprint away from any perceived threat at speeds up to 70kph. In contrast to semi-subterranean rabbits, hares spend their entire lives above ground, and though largely nocturnal, are routinely active at dawn and dusk, too. When not feeding or interacting with their compatriots, hares rest in any fields with good all-round visibility. Hunkering down in the vegetation or digging out a shallow impression in the ground, called a form, helps keep them out of sight and protects them from the worst of the elements.

“Brown hares are believed to have been introduced either during, or before, Roman times”

It was often assumed that the boxing was rival males fighting each other for mating privileges, but it has now been established this bout of fisticuffs is usually instigated by females fending off any overly amorous males. While hare society is not particularly complex, a dominance hierarchy tends to develop among the males, or bucks, whereby more experienced individuals will drive away those younger and less assertive, particularly during the mating season between March and July.

Nevertheless, with the female coming into oestrus for just a day each month, she often becomes the subject of considerable attention at this time. When fed up with this relentless hectoring, she will rear up on her hind legs before using her front legs to rebuff any suitor whose advances are not appreciated. Those males unwilling to take ‘no’ for an answer will then reciprocate this behaviour, with fur frequently flying whenever contact is made.

“The fisticuffs is instigated by females fending off amorous males”

For the experienced males, however, persistence appears to pay off, as they eventually break down her resistance and copulation ensues. With mating the sum total of the male’s involvement, his focus then switches to finding yet more receptive females. Capable of producing as many as four litters of between one and four leverets during a favourable breeding season, the females’ high productivity will help offset hares’ terribly short lifespans, where any individual reaching its second birthday can be considered to have beaten the odds.

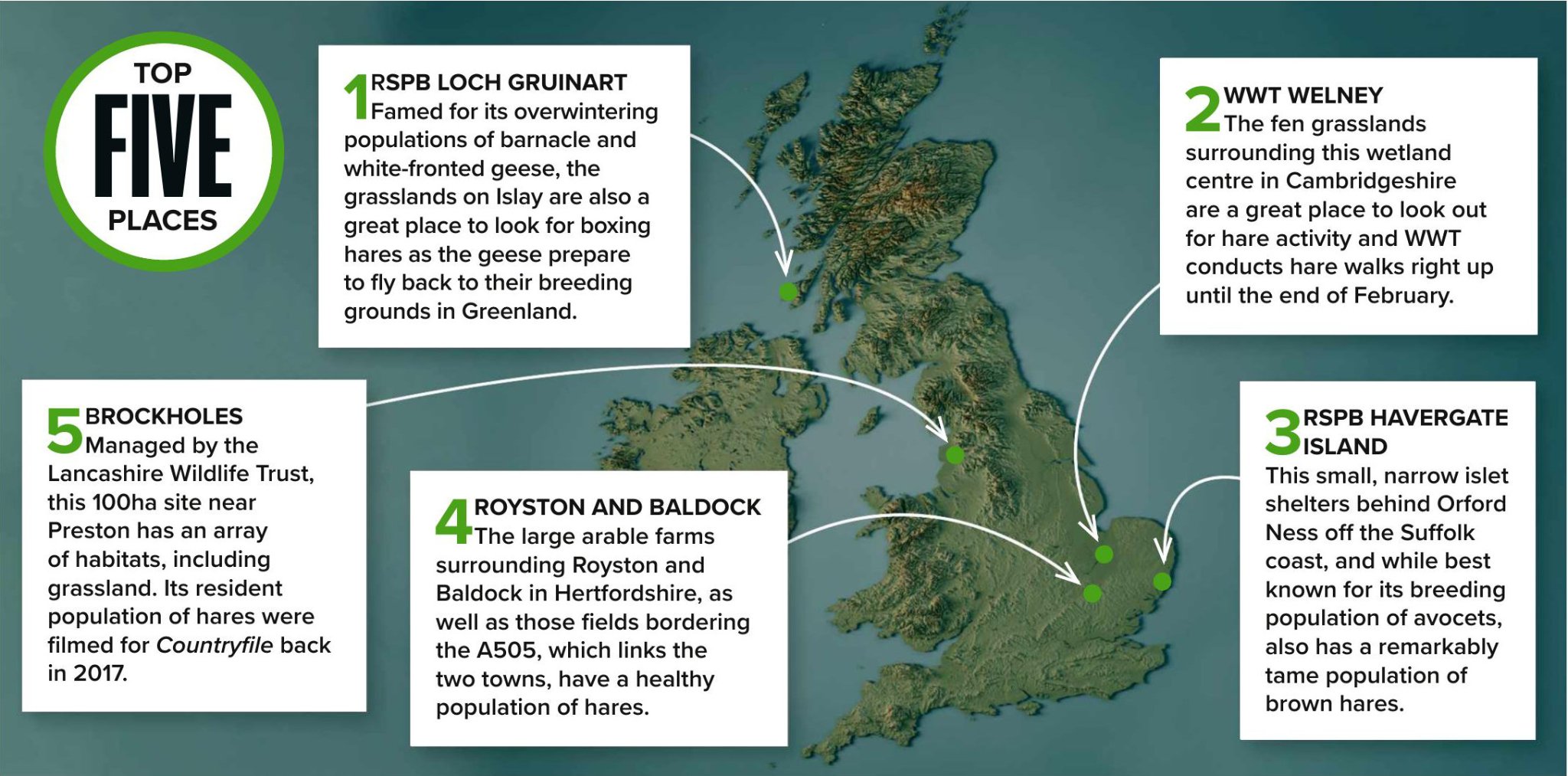

The number of hares on farms and grassland can differ widely across the countryside, with some locations holding healthy populations, while others appear to hold none. Generally speaking, the arable heartland of southern and eastern England is their stronghold, but the estimated British population of 800,000 has fallen substantially from a high point of about four million during the late Victorian era.

When trying to views hares, break up your outline by using a hedge or a car as a hide, for example. On private land, such as a farm, please stick to the public footpaths. And finally, do remember that if you are on foot, remaining downwind will help you get closer to that all-important ringside seat, as and when the action finally kicks off.

Catch up on all the episodes from Winterwatch

Did you know?

Brown hares require long grass and vegetation to hide in during the day but modern intensive agriculture has reduced its availability

LOOK CLOSER

Thumper

Unless physically attacked, brown hares make very few vocalisations, preferring to use their feet to convey messages. They often thump their front feet when challenging another hare, but only tend to strike the ground with their hind feet when warning of mortal danger – such as the sudden appearance of a fox.

Blazing a trail

Hares use well-established trails across fields and you can sometimes spot regularly spaced ‘bound marks’ where the impact of their large hind feet produces a shallow depression in the path’s surface. Also look out for the gaps in hedgerows made by hares passing through.

Shades of grey

While scanning for hares, keep an eye out for our native grey partridge – which has the unfortunate distinction of being one of our fastest declining birds. Distinguish them from the introduced red-legged partridge by the orange face and the dark horseshoe on their belly.

NEXT MONTH

Mike shares his tips on how to see wood ant nests