Nick Baker’s Hidden Britain

The popular naturalist, author and TV presenter reveals a secret world of overlooked wildlife

Close to you

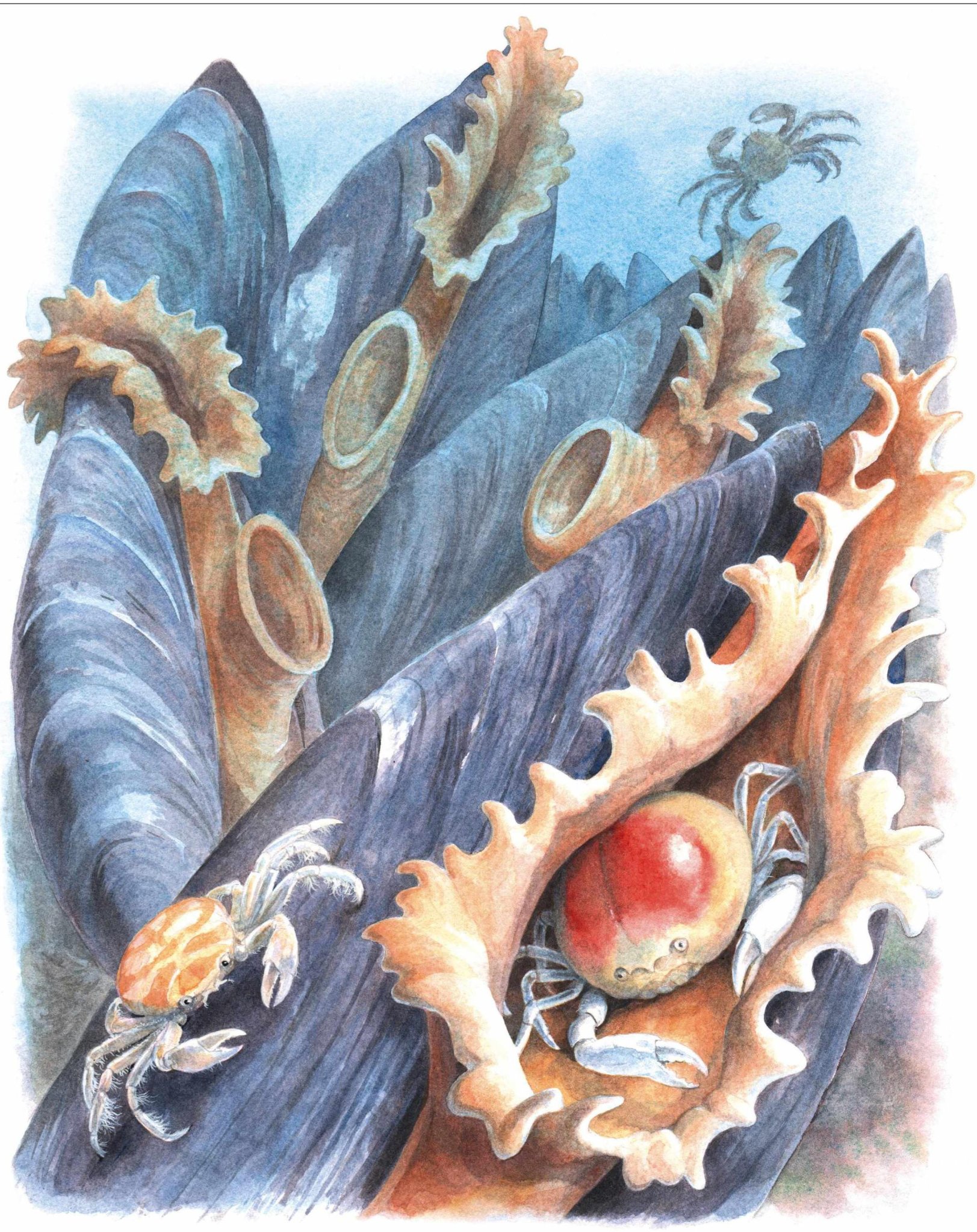

PEA CRAB

A small, parasitic pea-sized crab that’s most content living inside its bivalve host

NOT MANY SUBJECTS FOUND IN THIS column are best seen at the dining table, or more specifically, in this case, within a bowl of moules marinières. But next time you find yourself tucking into this tasty seafood dish, keep an eye open for a little extra: a pea crab (Pinnotheres pisum), also known as a mussel flea.

This tiny animal is one of the smallest crab species – a female rarely gets much larger than 12mm across – and is a parasite of mussels and a few other bivalve molluscs. Mussels are a tough nut to crack: their thick shells and lightning reflexes protect them from most small predators. But the pea crab has taken on this challenge, dedicating its life to breaching these defences to live within the protective enclosure of the shell. As the mussel sucks in seawater, edible particles are filtered out by the gills and gathered in a mucous rope, before being passed down a conveyor belt of ciliary hairs. The pea crabs simply help themselves.

The female crab never leaves the mussel. Almost twice as big as the male, she is virtually spherical. When carrying eggs, the large egg mass clutched to her underside is so big that she almost doubles in thickness and walking becomes impossible. Her life of leisure also means she has no need of a hard exoskeleton. The male, on the other hand, is a different beast. During the early stages of his life, he, too, is a resident of the mussels’ inner sanctum. But as he matures and the lure of sex calls, he takes risks. The adult females attract males by emitting a pheromone that wafts out of the mussel from its exhalent siphon. A male downcurrent will then slip out of his homely host to find her.

To aid his ease of exit and subsequent entry into his lady’s lair, the male is not only smaller, but flatter. He is also an excellent swimmer, possessing fringes of long hairs on his legs that act as paddles. Because of these field trips into the big wide world, he has many of the usual crustacean adaptations – ahardened exoskeleton and cryptic markings of browns and greys are useful in minimising the chances of coming to harm.

However, captive experimental studies with other species of pea crab have shown that even jinking in and out of mollusc hosts is risky. Many males get their legs trapped and amputated or, more seriously, can be crushed. Still, this odyssey is worth the risk for the males, as one mating could mean a considerable investment in the next generation. A single female pea crab can produce thousands of eggs – over 9,000 have been recorded. The bigger the host mussel, the more food it sucks in; and more food for the crab means it, too, can grow bigger and produce more eggs.

After about a month, the female’s eggs hatch. The free-swimming larval crabs then move out of their mussel home into the surrounding seawater and go on to join the plankton community. In its final freefloating stage, the pea crab larvae – known as megalopae – have swimming legs called pleopods along their tails, as well as large chemoreceptors. They are thought to use these adaptations to detect and swim towards their final mussel hosts, before being happily sucked in along with the mussel’s food to take up residence.

Pinnotheres pisum translates from Greek and Latin as ‘pea-like guardian of the lobe’. The ‘lobe’ probably refers to the mussel’s gills.

LOOK CLOSER

A parasite’s parasite

Just in case you thought the pea crab has an easy life, it, too, is prone to parasitism. A crustacean called Pinnotherion vermiforme, which measures just 1-3mm, infects the crabs – it lives inside the pea crab’s body cavity and diverts the crab’s resources (and the mussel’s!) to its own ends. Parasites of parasites are sometimes known as hyperparasites.