Q & A

Email your questions to wildquestions@immediate.co.uk

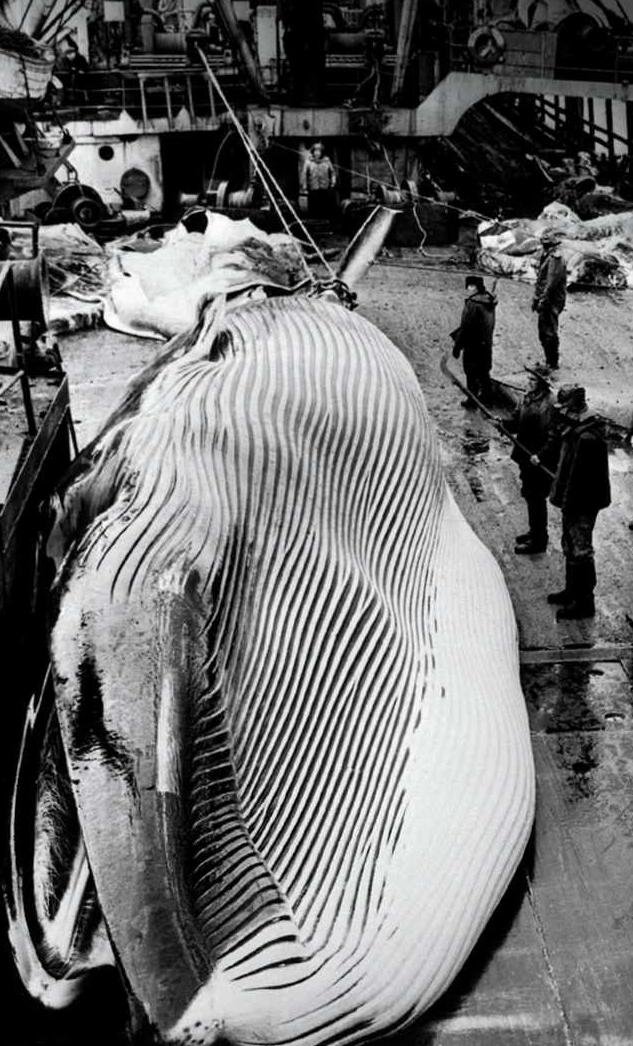

Have whales recovered since the whaling moratorium?

CHRIS VICK ANSWERS:

Sir David Attenborough recently said: “Fifty years ago, whales were on the very edge of extinction worldwide. Then people got together and now there are more whales in the sea than any living human being has ever seen.”

So, have the whales been saved? Well, yes and no. Certainly, there is a conservation success story to tell after the International Whaling Commission introduced a whaling moratorium in

1985-86. Some of the big species that hunters historically targeted, such as fin and humpback whales, are increasing in number in some regions. The population of the largest and most iconic species, the blue whale, is also recovering. But some species are still classified as Endangered or Vulnerable, and the North Atlantic right whale is Critically Endangered.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the seven or eight ‘great whales’ that were hunted commercially are a relatively small percentage of the total whale species that exist. Those whales that were targeted by hunters probably number no more than 1.5 million, and perhaps half of those are minke whales.

Sadly, some whale hunting still occurs today, and there is also a growing plethora of often poorly quantified and understood issues that are threatening whales worldwide, such as fishing and global warming, and noise, oil, plastics and chemical pollution. There is real concern that whales are now vulnerable to threats that are increasing and compounding.

Can spiders hear?

STUART BLACKMAN ANSWERS:

As the old joke goes, you can prove that a spider’s ears are on its legs, because if you pull all its limbs off, it doesn’t come when you call its name.

Actually, spiders don’t have ears as such, but they do indeed hear with their legs, by means of a smattering of specialised fine hairs that are stimulated by airborne vibrations and connected to nerve cells at their base.

However, at least one species augments these capabilities by constructing an enormous ‘eardrum’ 10,000 times bigger than itself, sitting right in the middle of it and picking up the vibrations through its feet. In fact, the orb webs spun by the bridge spider (Larinioides sclopetarius) – a UK species so-called because it is most commonly encountered on human-made structures near water – are more sensitive to acoustic vibrations than any known conventional eardrum.

Is rosehip syrup full of vitamin C?

DAVE HAMILTON ANSWERS:

With a bit of care to filter out the tiny, itching hairs within the fruit, rosehips can be mashed up and stewed to make sweet and tasty rosehip syrup – great over pancakes or ice cream, or diluted with hot water for a cosy winter drink. Many online articles sing the praises of this syrup for its health benefits – particularly that it is high in vitamin C. In fact, during World War II, enemy blockades prevented the importation of fruits high in vitamin C, such as oranges and lemons. And as a result, the government at the time feared the population would suffer nutritional illnesses, such as scurvy. Their solution was the mass-scale picking of rosehips to make rosehip syrup.

Although the syrup-making process usually involves boiling the pulped rosehips and depleting much of the vitamin C, there is so much of this vitamin in a hip, that there is still enough left in the end product to prevent nutritional problems.

RECORD BREAKER!

What was the largest dinosaur?

All the contenders for this title belong to a subgroup of sauropods called the titanosaurs. Patagotitan mayorum may have measured 37.2m in length, although some scientists believe this is an overestimate. However, Argentinosaurus may have measured between 37-40m in length. The truth is we don’t know, as scientists can only estimate the size and weight of these dinosaurs.

FACT.

Gorillas rarely drink water as they can obtain all the moisture they need from the vegetation they eat. Dian Fossey once wrote that mountain gorillas “seem to dislike water in general”.

How do fish get tongue-eating lice?

JOANNA BAGNIEWSKA ANSWERS:

Fish are prone to numerous parasites, and one nightmarish example is the tongue-eating louse. This trilobite-like crustacean enters the fish via the gills, and moves into its mouth. There, the louse severs the blood vessels to the tongue, leading to its degeneration, and attaches itself to the remaining stub – as an organ replacement of sorts. Fish tongues are not muscular, but bony and tough, and rigid lice can mimic them surprisingly well. Interestingly, all tongue-eating lice start off as males and only turn female when they reach over a centimetre in length. If two lice parasitise the same fish, the smaller one remains in the gills as a male and will pop over into the fish’s mouth for a quick conjugal visit to the larger female there.

What are ant supercolonies?

RICHARD JONES ANSWERS:

Like medieval city states, neighbouring ant colonies constantly bicker over land and resources. Enemy ants are detected by their genetically determined smell, so while worker sisters in the same nest have similar scents, foreign interlopers are repulsed.

However, it is possible for ant nests to connect and form ‘supercolonies’. For instance, when the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile, was accidentally introduced to Europe in the 19th century, the gene pool was so shallow and the colonies so closely related to each other that they did not recognise neighbouring nests as the enemy, just as extended family.

That family now runs for 6000km along the coasts of Portugal, Spain, France and Italy, and contains millions of interconnected nests and countless billions of happily cooperating sisters.

WHAT ON EARTH?

Sweet little mystery

Sometimes, the question “What on Earth?” leaves even the experts stumped. A survey of our resident entomologists has failed to identify this unusual specimen, photographed in Peru. All we can say is that it’s almost certainly an insect larva and quite possibly one that has built a protective silken cocoon around itself prior to pupating. But just what sort of insect it is remains a mystery. Contenders include sawfly, hoverfly, beetle, butterfly and moth. Ideally, we’d hang around and see what eventually emerges, but we fear it might be a little late for that.

FAST ANSWERS

What is a ghost apple?

During the winter of 2019, images of hollow, apple-shaped ice formations resembling cut-glass fruits began circulating on the internet. Dubbed ‘ghost apples’ they confused and delighted all who saw them, but what were they caused by? During the winter, apples can rot from the inside – flesh behind the skin breaks down to the consistency of apple sauce. Freezing rain then ‘sets’ on the outside of these rotten apples, forming a hard, icy casing, before the mushy insides fall out, leaving an intact ghost apple.

What is a sea hare?

Related to the sea slugs of the nudibranch order, sea hares are a similar-looking group of herbivorous marine gastropod molluscs. One of the most notable features of the group are their ‘ears’, protruding from the top of the head, which somewhat resemble the long ears of a hare. These are actually a pair of rhinophores – structures that can detect chemicals in water.

How does a kagu use its wings?

Lacking the muscles required for flight, the mostly flightless kagu bird still uses its wings in a variety of ways, including courtship displays and gliding through the forest. It also exhibits the ‘brokenwing’ display, where a parent fakes an injury in order to lure a predator away from its chick.

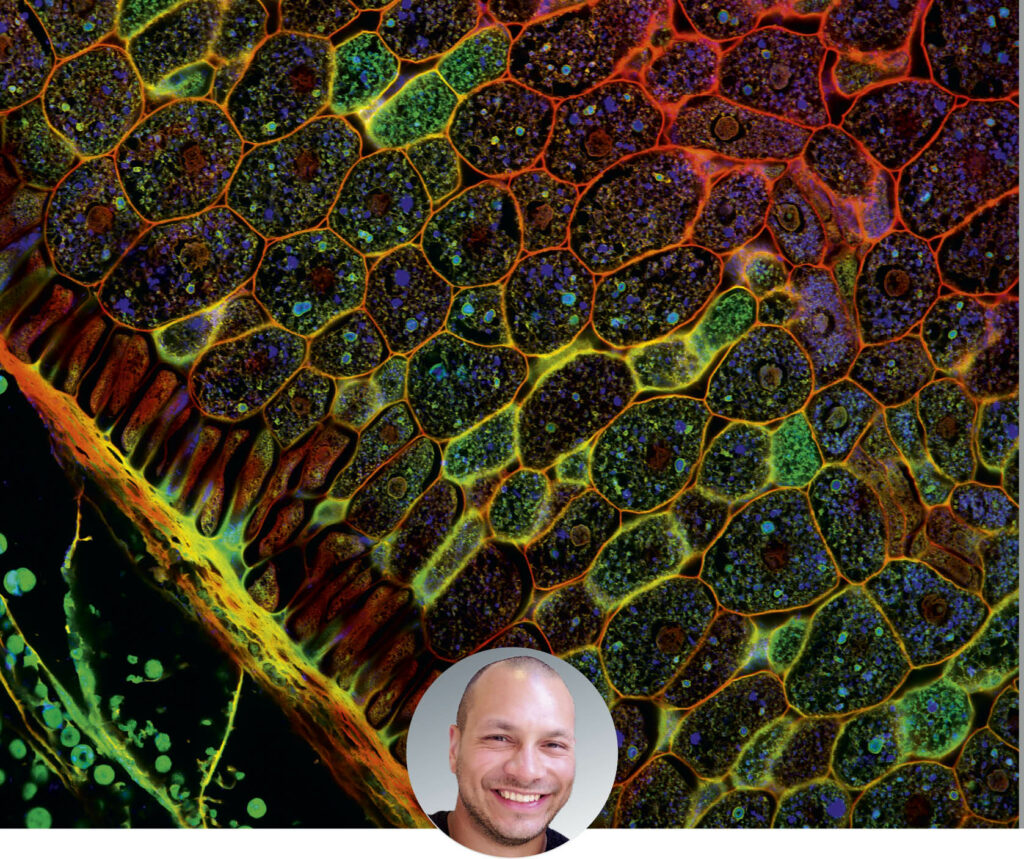

INSTANT EXPERT

Cells: the basic units of life

GIVEN THAT THEY CONTAIN the biological molecules and machinery required by all life forms, it’s ironic that cells were named after empty spaces. When the 17th-century polymath Robert Hooke looked down a microscope at the structure of cork, its repeating units of spaces reminded him of the sleeping quarters in a prison or monastry. Hooke called those units ‘cells’, from the Latin for ‘little rooms’.

Is all life made of cells?

It depends on how you define life! Viruses aren’t made of cells, but some biologists consider them alive. A virus can’t replicate without using a host cell, though, so we can sidestep the philosophical discussion of “What is life?” and say all life uses cells.

Life forms that are made of cells are called organisms. They’re either unicellular (single-celled) – bacteria, for example – or multicellular. Unicellular organisms must do all the work needed to sustain life, but multicellular life forms can have a body with a division of labour: different types of cell play specific roles in the organism.

What do cells have in common?

Every cell has a fatty membrane that establishes its boundary and controls which substances go in or out of its watery internal fluid, the cytoplasm. A cell will almost always contain genetic material, too.

And how do they differ?

The biggest distinction between cells is how they hold genetic material. In eukaryote cells, the DNA is enclosed with a ‘nut’ or envelope called the nucleus (hence eukaryote meaning ‘true nut’ in Greek). Meanwhile, in prokaryote cells – bacteria and archaea, descendants of life forms that didn’t evolve to have a nucleus – the DNA floats freely in the cytoplasm (prokaryote means ‘before nuts’ in Greek).

Eukaryote cells are more complex because they’re organised into compartments with structures known as organelles (‘little organs’) with separate functions, analagous to the organs of a body – as in energy-generating mitochondria that breathe oxygen like lungs.

A cell’s contents vary depending on a cell’s function. Many contain something like muscle and bone – the cytoskeleton – for shape, support and internal movement. Other cells (such as plant, fungi and bacteria) may be surrounded by rigid cell walls.

How do cells divide?

Prokaryotes duplicate genetic material then simply split in two by binary fission. But in eukaryotes, cell division is often complicated by having DNA distributed among numerous pairs of chromosomes, which are packaged inside the nucleus and have to be aligned before they’re copied.

Eukaryote cells divide by either mitosis or meiosis. Mitosis involves one round of division, meiosis involves two rounds. Meiosis is the process that creates sperm or eggs and, because their DNA isn’t duplicated during the second round of cell division, they end up with unpaired chromosomes. These combine into new pairs via sexual reproduction, when the cells from each parent fuse to form an embryo.

How can one cell develop into so many different types?

That’s the miracle of life! Incredibly, a single-celled embryo repeatedly divided to form everything from your brain to your belly button. The path to making different cell types is like a plant whose stems represent stem cells with the potential to give rise to leaves, the specialised cells.

Embryonic development seems more amazing still when you consider that different cells (over 200 types in a human body) carry the same genetic instructions. As a cell divides, it reads genes to make proteins, which determine its features and behaviour. That can even cause a cell to ditch its DNA: in humans, after making the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin, a red blood cell will use a weird kind of division to pinch off its nucleus and make space to pack in more haemoglobin.

Are any body parts not made of cells?

Loads! The most apparent are parts such as feathers and scales, claws and hooves, which come from the integumentary system – an animal’s skin and appendages – and are partly composed of the protein keratin. Even when an organism isn’t made entirely of cells, they’re mostly made by cells.

NEXT MONTH WITH JV

PARASITISM

Survival through exploitation

BBC WILDLIFE EXPERTS