PORTFOLIO

The deer and the departed

Intimate photos of roe deer reveal insights into family life in England’s graveyards

Roe deer feature on Wild Isles, on air and iPlayer from early spring

Finding sanctuary (above)

A doe and her kid peer around watchfully on an early July morning, while foraging in a city cemetery in Wiltshire. The burial grounds pictured in this portfolio all stand on the edge of woodland, providing ideal habitat for roe – one of Britain’s only two truly native deer species, along with red – allowing them to retreat into the shadows of the surrounding trees if disturbed.

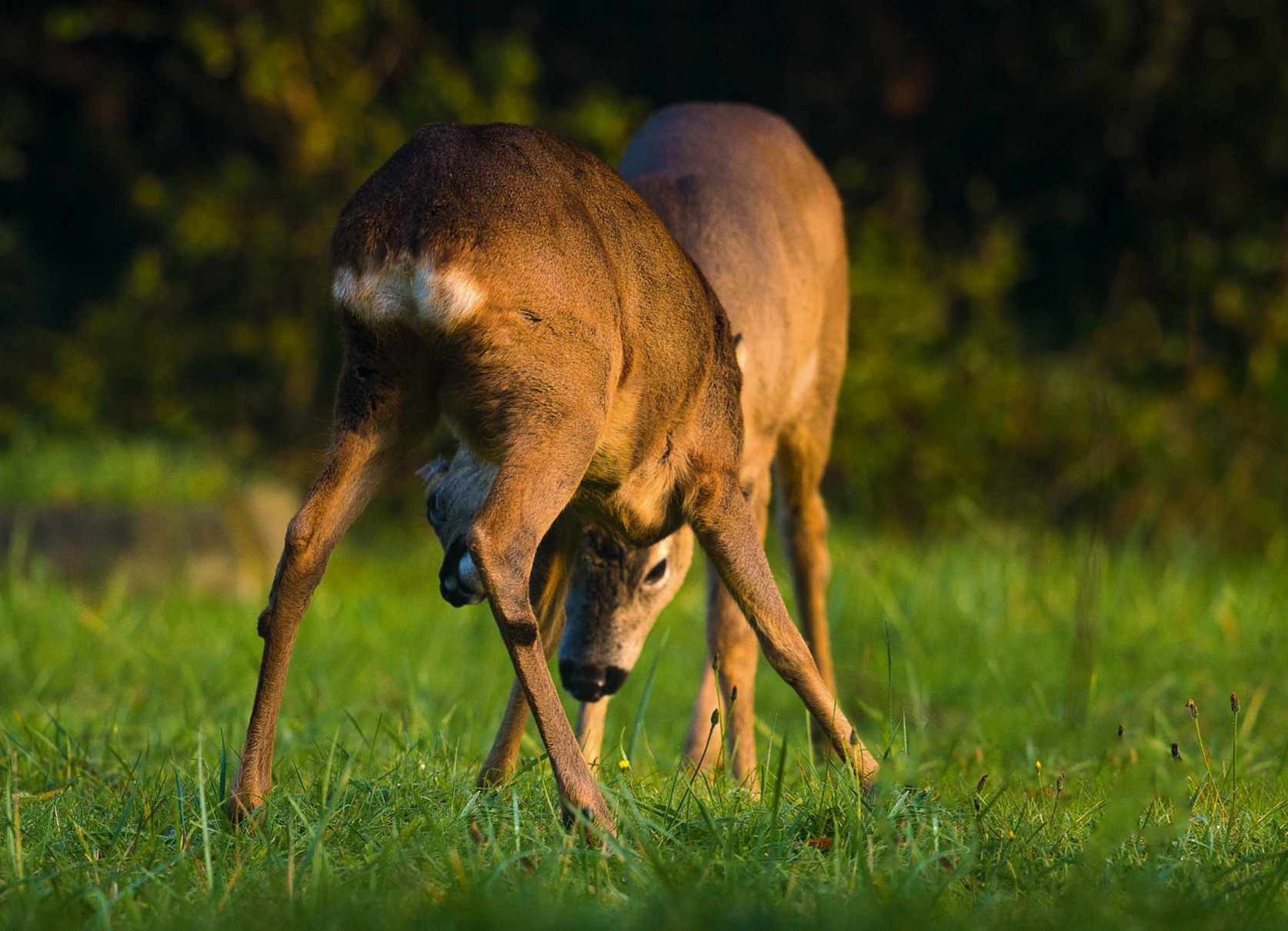

Nursing times

Young twins suckle their mother, who nudges her offspring to help them find her teats. These kids are just two or three weeks old, born in May after five months’ gestation – though nine after mating; roe deer are among the few British mammals that employ delayed implantation of fertilised embryos. Twins are typical, though single kids and triplets are sometimes born.

Building bonds

Tender licks and nudges help nurture the bond between mother and young as she moves her family around the semi-urban environment of a Surrey cemetery. Wildlife photographer Jules Cox spent four years following this particular doe and her succession of offspring, which also feature in the Wild Isles series airing on BBC One and iPlayer from early spring.

Be still

A two-week-old kid lies motionless and silent, largely concealed in long grass, while mother forages nearby in a Surrey cemetery. That instinct to remain completely still and hidden, which kicks in right after birth, is vital for young roe deer. In their first weeks, kids are highly vulnerable to predation from red foxes and to dog attacks.

Grave squirrel

Roe deer share these pockets of greenery with other wildlife, including grey squirrels. Jules spotted this individual in West London. “This peaceful environment is a real haven for wildlife,” he says, “allowing people in towns and cities to develop a relationship with nature.”

Too big to bite

Fortunately for this four-month-old roe deer, pictured in a Sussex cemetery in September, it’s already too large to fall prey to a hungry red fox. Kids grow rapidly on their mothers’ rich milk and on the abundant browsing and grazing available in this urban habitat, reaching up to 25kg when fully mature.

Making an impression

Not just a hoofprint, this 4cm-long scrape made by a roe buck has been anointed with scent secreted from interdigital glands in the clefts of his hind feet. Bucks use scrapes to mark their home ranges, also rubbing branches and other vegetation with scent glands on their foreheads. They’re only seasonally territorial, between about March and August.

Dappled by design

A week-old kid’s brown fur is spotted with creamy markings, providing excellent camouflage in the roe deer’s preferred habitat at the edges of woods and forests. These spots will fade over the next couple of months. Adults sport beautiful rust-red coats in summer, fading to a duller grey-brown in winter when they also form larger groups.

Night of the hunter

Cemeteries come alive after dark, as various creatures join roe deer foraging and hunting in their long grass and shrubs. Jules photographed this barn owl perched on a stone cross in a Suffolk graveyard.

Head to head

An adult buck spars with a yearling, which will need to hone fighting skills if it’s to win the right to mate. Males become highly aggressive during the rut, from mid-July to late August, defending territories and vying for access to does. Fighting usually consists of locking antlers, twisting and shoving, which can sometimes cause serious injuries.

Drawn to dusk

Though most commonly seen at dawn and dusk, when fewer people are around and they’re most active, roe deer forage day and night. In fact, they feed every three or four hours, spending long periods lying and ruminating between grazing and browsing.

Heavenly horns

This impressive buck, for many years the dominant male in this Surrey cemetery, is a ‘six-pointer’ – meaning that each of his antlers is branched into three points. The degree of ‘pearling’ – the distinctive small nodules on the antlers – can help indicate a buck’s age. He’ll cast these antlers in October before starting to grow a new pair almost immediately.

Budding thief

A rose left at a graveside provides a colourful morsel for this doe in a Wiltshire cemetery. “While it can be frustrating when floral tributes are eaten, many visitors enjoy the feeling of solace that these shy, gentle animals can bring in times of bereavement,” says Jules. Roe deer enjoy a varied diet, feeding on tree buds and leaves, ferns, heather, grasses and flowers.

Eyes peeled

A kid hiding in ferns fringing a cemetry is a fairly common sight – and becoming more so. Heavily hunted since prehistoric times, roe deer were extirpated from England, Wales and southern Scotland during the 18th century. The population has since rebounded, with perhaps 500,000 individuals thriving across much of the island. Numbers are growing in towns and cities: watch for roe deer in your local woods, parks – and, of course, cemeteries.

Go to Go Wild to read more about the BBC One Wild Isles series (which features deer from this Portfolio) and enjoy a Wild Isles supplement with our next issue, too.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Jules Cox is a UK-based photographer with a passion for the wildlife of the British Isles and far north. For the past 10 years he has specialised in photographing wild roe deer, and was a consultant on BBC One’s forthcoming series Wild Isles.

See more of his work at julescoxphotography.com.