Back to Nature

REWILDING ARGENTINA

In Argentina’s Iberá Wetlands, a showcase initiative is returning several keystone species and restoring this wondrous ecosystem

AT THE AGUARÁ CONSERVATION CENTRE, a stone’s throw from the Argentine city of Corrientes, Mburucuya the red-and-green macaw is ready to fly. As a whistle sounds, the stunning, vermilion-plumaged parrot spreads her wings and launches herself towards the nearest food tray, 25m away down the huge enclosure. She has already followed the same trajectory numerous times today, but practice makes perfect.

Having been born in captivity, Mburucuya needs to master a range of unfamiliar skills before she can venture into the wild. Nearly a year of intensive training has strengthened her wings for long-distance flying. It has also taught her how to avoid predators, socialise with fellow macaws and seek out food. As part of a group of birds performing a similar journey, Mburucuya will soon be released into the Paraná forest of the nearby Iberá Wetlands, where she and fellow returnees will play an increasingly important role dispersing fruits and large seeds from a number of native tree species.

Red-and-green macaws, or gua’a pytã as they are called by the indigenous Guaraní people of the region, were once common in the forests of northern Argentina. But by the 20th century, the exotic pet trade, illegal feather trafficking and deforestation had driven them to local extinction. Their comeback in the Iberá Wetlands, which has so far seen 20 birds released into the wild, has come about thanks to the efforts of Rewilding Argentina (RA), a pioneering Argentine NGO that works to establish protected areas, rewild ecosystems and enable local communities to benefit from nature.

“The Iberá Wetlands are a sweeping 13,000km2 wilderness of open water, marshland, grassland and forest”

“This is the first time that a locally extinct bird has been reintroduced in the history of Argentina,” explains Sebastián Di Martino, RA’s conservation director. “As forest regenerators, the growing population of macaws within Iberá will help to create a more complete and functional ecosystem. Reintroducing keystone species such as red-and-green macaws is critical to the revitalisation of these wetlands – a revitalisation that is not only good news for nature itself, but for local communities as well.”

One of the most important freshwater ecosystems in South America, the Iberá Wetlands (Esteros del Iberá) are a sweeping, 13,000km² wilderness of open water, marshland, grassland and forest, of which about 7,770km² are protected as the Great Iberá Park. Located in north-east Argentina’s Corrientes province, about 640km from Buenos Aires and just south of the border with Paraguay, the wetlands are second only in size to the Brazilian Pantanal.

In the indigenous Guaraní language iberá means ‘brilliant waters’, and the adjective is more than apt. A magical place for wildlife enthusiasts, the Esteros del Iberá are filled with dazzling biodiversity, boasting more than 4,000 animal and plant species. These include iconic species such as the jaguar, capybara, black caiman and giant anteater, not to mention more than 360 species of birds, including the greater rhea, crimsoncrested woodpecker, rufescent tiger heron and spectacular strange-tailed tyrant.

YET DESPITE ITS NATURAL abundance, Iberá hasn’t always been such a vital oasis. During the 19th and 20th centuries, illegal hunting, cattle ranching and intensive forestry had a hugely negative impact on the wetlands, with many species disappearing from the landscape completely.

“I first came here in the early 1990s and made several survey flights over Iberá,” says Sofia Heinonen, a biologist from Buenos Aires who is now RA’s executive director. “There were hardly any large wild mammals. Just lots of cattle – and not much else.”

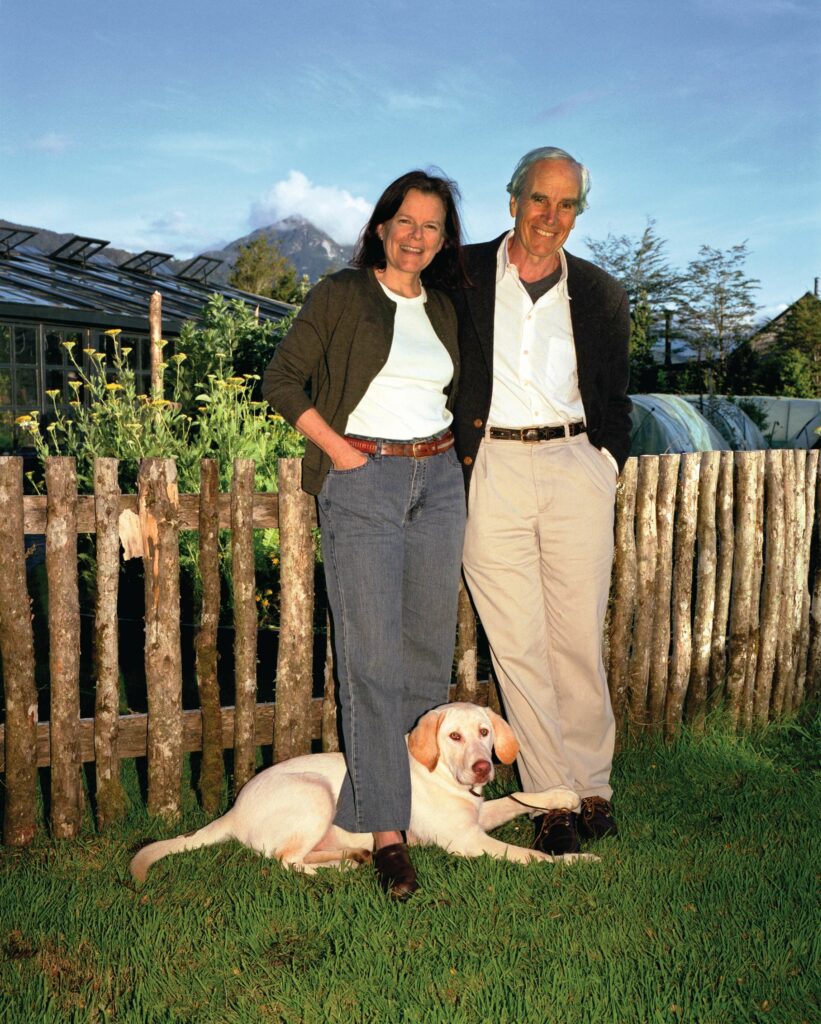

Also on board those flights were Americans Doug and Kris Tompkins. Starting in the 1990s, the husband-andwife conservationists – he, cofounder of clothing companies North Face and Esprit, and she, the former CEO of clothing company Patagonia – began buying up strategically located tracts of land across Argentina and Chile to protect through their nonprofit organisation, Tompkins Conservation. From 1997 onwards, this included growing amounts of land in the Iberá Wetlands.

In 2010, RA spun off from Tompkins Conservation (which is still a strategic partner, collaborating on rewilding efforts in Argentina) and now runs rewilding projects in the Iberá Wetlands, as well as a burgeoning portfolio of other rewilding initiatives in Argentina – from the Amazonlike El Impenetrable National Park in the Gran Chaco region (north-west of the Iberá Wetlands), to the high-plateau Parque Patagonia, more than 1,600km south, and Patagonia Azul (Blue Patagonia) – its newest addition – where RA is rewilding an entire coastal ecosystem (see box on page 74).

“Nobody had attempted jaguar reintroduction before, so we were breaking new ground all the way”

Doug Tompkins died in 2015, but for her own part, Kris, who features in Wild Life, a new National Geographic film, maintains a huge interest in and affection for Iberá, where her own rewilding journey began.

“When Doug and I first started buying land in Iberá, the idea was to simply solidify territory and protect the landscape,” she explains. “Then we discovered that so much wildlife was missing, that species such as the jaguar, giant otter, giant anteater and redand-green macaw had been extinct here for many decades.”

“Doug and I understood the importance of keystone species in maintaining healthy, balanced nature. Iberá made us realise that we weren’t just in the business of creating national parks. Only by embarking on a long-term rewilding programme could we hope to transform these wetlands into a fully functioning ecosystem once again.”

ON SAN ALONSO ISLAND, IN the heart of Iberá, Malú – a five-year-old jaguar from Uruguay – demonstrates one reason why these big cats top the food chain. Toying with a large bone, she applies the full force of her jaws (stronger than any feline), shattering it with a resounding crack. With jaguars hunted out of existence in Iberá 70 years ago, the influence of this formidable apex predator, the flagship species of local rewilding, has been sorely missed.

Those who visit Iberá can’t help but notice the preponderance of capybaras – South America’s most iconic, supersized rodent. One of the most obvious signs of natural imbalance in the wetlands is the large groups of these seemingly tame, regal-looking animals, basking on the ochrecoloured roads or mud-bathing in roadside pools. Until recently, there was little for them to fear in the landscape, with jaguars long gone and pumas thin on the ground.

The story of the jaguar’s demise in Iberá has been reflected across the vast majority of Argentina. There are now fewer than 300 wild jaguars left, mainly in the provinces of Salta, Jujuy and Misiones, in the north-west of the country. In the wetlands, however, the recent efforts of RA are slowly turning the tide in the big cat’s favour.

Doug Tompkins had been fascinated by the idea of returning jaguars to Iberá since he bought the San Alonso estate in 1996. But it wasn’t until 2013, following the reintroduction of other species (such as the giant anteater and pampas deer), that a jaguar reintroduction programme on the island eventually got off the ground.

“Nobody had attempted jaguar reintroduction before, so we were breaking new ground all the way,” says Di Martino. “It took millions of dollars just to build the huge pre-release enclosures where the animals are prepared for their long journey into the wild. Then there was all the paperwork involved in bringing together captive jaguars from zoos and rescue centres across South America. It was a mammoth undertaking.”

On 6th January 2021, conservationists on San Alonso finally opened up a pen that held two four-month-old jaguar cubs, Karai and Porã, and their mother, Mariua – who had been brought from Brazil – giving them freedom to roam across the entire Great Iberá Park. It was a headline-grabbing milestone for Iberá rewilding.

“That was one of the most incredible days of my life,” says Kris Tompkins. “I never thought it could happen. But when those jaguars walked out of the gate I thought, ‘I could die tomorrow.’ Everything else is just icing on the cake.”

Two years later, following further releases, Iberá’s wild jaguar population stands at 12, with four cubs now born outside the San Alonso enclosures. With its abundance of prey, the carrying capacity of the Great Iberá Park is estimated to be about 100 big cats – afigure RA estimates could be reached within a decade, with releases set to continue.

AS DAWN BREAKS OVER THE beautiful Rincón del Socorro, an army of capybaras is already out in force, nibbling the plush, palmstudded lawns of this exclusive property. From time to time, groups of greater rhea pick their way daintily through the docile herbivores, shaking their wings and pecking at the clover. The largest birds in South America, these flightless avians stand at over a metre high and can run at speeds of up to 65km per hour. Today, however, nobody seems to be in that much of a hurry.

Doug Tompkins acquired Rincón del Socorro, which was then a working farm on the edge of the Iberá Wetlands, in 2001. He and his team restored and expanded the old farm buildings, removed cattle from the fields, rolled up hundreds of kilometres of wire fencing, and used the property as a base from which to rewild the surrounding landscape, as well as hosting the growing numbers of visitors keen to explore the area.

A short drive from Rincón del Socorro’s main collection of buildings is an enclosure containing another group (two males, two females) of stunning and ecologically important felines. Ocelots are the third-largest wild cat in South America – after the jaguar and puma – and are also considered keystone species because they help to keep small mammal and bird populations at a healthy level. Balam, one of the male ocelots, has recently gorged himself on an armadillo, and is dozing in the shade of a small tree. In contrast with the jaguars on San Alonso, it’s safe to enter his pen and approach to within a few feet. Balam lifts his head and emits a curious growling hiss, but otherwise ignores the intrusion. Up close, his gorgeous dappled coat is all the more captivating.

After the successful releases of jaguars in Iberá, it’s the turn of the ocelot. Decades of hunting mean the animal is virtually extinct in the wetlands, and fewer than 10,000 (maybe only 1,500) are thought to remain in the whole of northern Argentina.

“We will probably release the ocelots into Iberá some time in 2023, when all the animals have acquired the necessary hunting skills and the females have kittens,” explains Di Martino. “Releasing females helps to tie the males to the area, otherwise they would just wander off in search of a mate.

“We expect to release giant otters into Iberá soon, too, and pumas are gradually making a comeback of their own accord. As the Iberá rewilding programme continues, populations of apex predators will gradually grow and diversify, though there’s a long way to go before they reach natural levels.”

Even before they began rewilding, RA realised that releasing animals into Iberá would be pointless if the drivers of their disappearance were still at work. This meant shifting local industry and commerce away from destructive activities such as farming, hunting and timber extraction, and towards a sustainable, nature-based economy.

“We knew we had to develop naturebased tourism as a way for local people to derive value from the park,” says Marisi López, RA’s parks and communities coordinator. “Otherwise the old ways would have persisted. We had to change people’s mindsets and show them that live animals are way more valuable than dead ones.”

Over the past decade, RA has invested heavily in developing park infrastructure, as well as educational, training and other outreach programmes. Every time a jaguar is released, for example, local communities are given a presentation and invited to the park. Iberá has also been promoted as one of Argentina’s top wildlife-watching destinations, and is becoming better known overseas. As tourism grows, more and more locals are becoming involved in its rapidly evolving regenerative economy.

Wildlife guide Domingo ‘Mingo’ Rene Gonzalez typifies Iberá’s economic transition. A former gaucho (cowboy) and hunter, for the past 15 years he has offered horseback rides through the wetlands, and works closely with RA.

“A few generations ago, the wild animals here were thought of only in terms of their meat and skin,” he says. “Now people can see the benefits they bring and understand the value of bringing back nature. Today, to live in Iberá is something to be proud of.”

Beyond Iberia

Five more South American rewilding initiatives

Patagonia National Park, Chile

An iconic species of the Patagonian steppe – and Chile’s largest native bird – the Darwin’s or lesser rhea plays a fundamental role in creating and maintaining healthy grasslands by dispersing seeds. Yet in Chile’s Aysén region, in Patagonia, more than a century of overgrazing, hunting and nest destruction has threatened the bird’s survival. Rewilding Chile (formerly Tompkins Conservation Chile) has been releasing birds into Patagonia National Park in Aysén since 2014.

Minas Gerais, Brazil

Comuna do Ibitipoca is set in a forest reserve in the Mantiqueira Mountains, near the Brazilian city of Lima Duarte, in south-east Minas Gerais. The 6,000ha nature-tourism resort is reintroducing species missing from the local Atlantic rainforest, with licences to reintroduce the tapir, the red macaw, the muriqui (woolly spider monkey) and two spectacular birds – the solitary tinamou and the black-fronted piping guan.

Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

Exploited for meat and oil, giant tortoises were one of the most historically decimated species on Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands. Iniciativa Galápagos (once the Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative), a collaborative effort led by Galápagos Conservancy and the Galápagos National Park Directorate, aims to restore tortoise populations across the archipelago, including on islands where they are currently extinct.

Peruvian Amazon, Peru

The rewilding efforts of Peruvian NGO, Hoja Nueva, are focused on the rescue, rehabilitation and reintroduction of keystone species in the Peruvian Amazon, such as jaguars, ocelots, margays and anacondas. Hoja Nueva specialises in carnivores (particularly cats, reptiles and medium-sized predators) because of their ecological importance, their prevalence in wildlife trafficking and the fact that there are no other centres dedicated to their reintroduction in the area. The primary aim is to stabilise and reinforce wild animal populations to ensure long-term survival.

Patagonia Azul, Argentina

Situated on the coast of southern Argentina’s Chubut province, in a key location for biological diversity in the Argentine Sea, this RA project works to protect and restore marine ecosystems to promote a new restorative economy through marine tourism and regenerative production. It’s a new national park, rich in wildlife, with more than 60 protected islands and bays that serve as feeding, breeding and nesting grounds for species of birds and marine mammals such as whales, orcas, dolphins and sea lions. Terrestrial species include guanacos, lesser rheas and Patagonian maras (a large rodent).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Daniel is a journalist and photographer with a focus on conservation. Rewilding expertise for this piece was provided by Cain Blythe, CEO of rewilding consultancy Ecosulis