Nick Baker’s Hidden Britain

The popular naturalist, author and TV presenter reveals a secret world of overlooked wildlife

Disco Inferno

GREEN-BANDED BROODSAC

The parasitic flatworm that turns a snail’s eyestalks into colourful, pulsating glowsticks

THE GREEN-BANDED BROODSAC – what kind of a name is that? Normally we name an animal after the appearance or behaviours of the adult, but in the case of the fluke Leucochloridium paradoxum, unless you want to go poking around the guts of snails or the bums of birds, its broodsac – amembranous sac containing larvae – really is the most visible part of this parasitic flatworm’s life. And when I say visible, it’s no exaggeration.

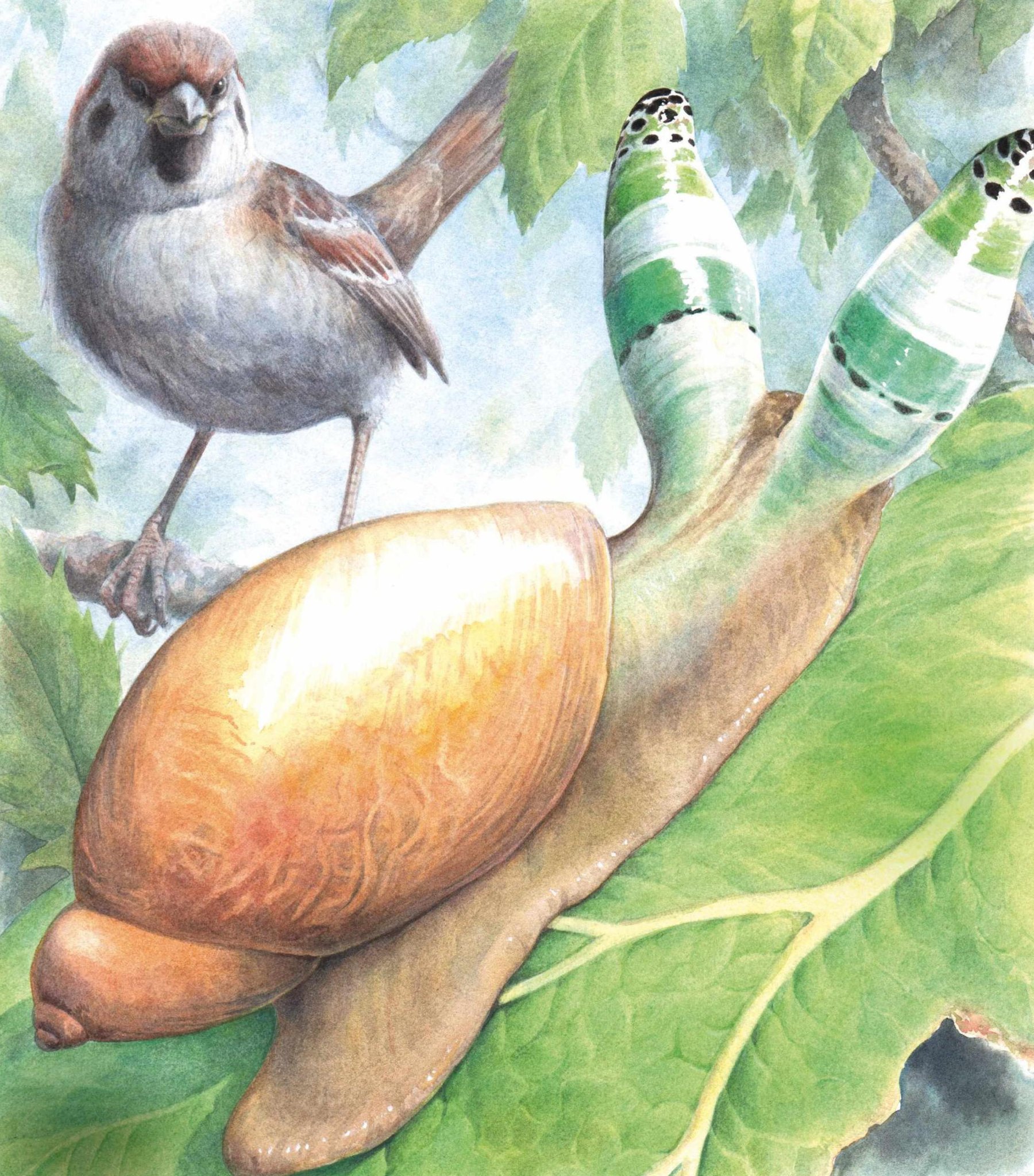

If you’re lucky, you might come across the unassuming amber snail (Succinea putris) putting on an uncharacteristic and extrovert performance. With its eyestalks pulsating in high-contrast patterns of green, black and red, you are witnessing the phenomenon that gives this fluke its name. These are the fluke’s broodsacs and they are part of a complicated life-cycle that involves a bird, a snail and a fluke.

It all starts with a snail stumbling upon a dollop of nutritious bird poo containing the eggs of the fluke: this is species jump number one, from a bird to a snail. These eggs then hatch in the snail’s gut, and larvae called miracidia find their way into the snail equivalent of a liver. Here, a larva can become a ‘sporocyst’; the headquarters from which to initiate its takeover bid of the snail’s life, dreams and eyestalks.

“Birds find these eyestalks irresistible”

The parasite has to accumulate nutrients to fuel the next stages of its life. It doesn’t look like much – just a blob of stringy white gristle without clear features or a mouth. Instead, the encysted fluke sends out tendrils of tissue that ramify through the snail’s body, absorbing nutrients directly through its skin and, in doing so, diverting the snail’s food.

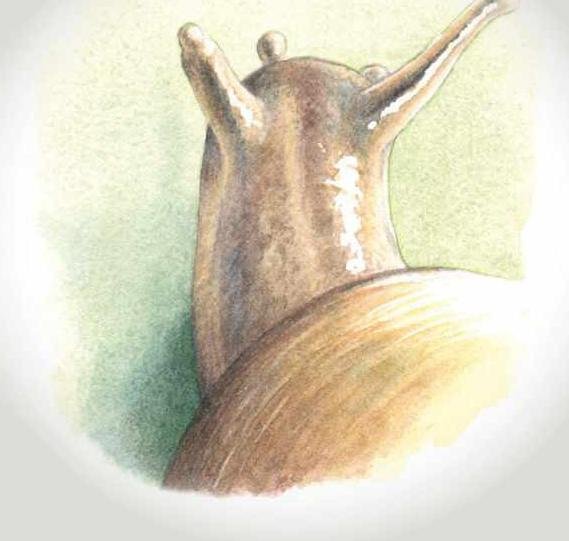

At maturity, the sporocyst grows arms that snake through the snail’s body and seek out the snail’s eyestalks. Here, the beginnings of one of nature’s most bizarre and sinister processes take place. The sporocyst in the snail’s ‘liver’ produces another form of larvae. These ‘cercariae’ migrate to the broodsacs that are now developing in the snail’s eyestalks. With up to 250 of these larvae in each broodsac, each covered in a protective mucous coating, room is tight and the eyestalks swell and distort; the snail’s skin gets stretched so thin the parasites can be seen within.

The snail can no longer retract its eyestalks, and it is now that the light show begins. If the amber snail was an introvert before, it has now come out as a mollusc fit for Mardi Gras. The effect is mesmerising, as the coloured bands of the boldly patterned broodsac throb at a frequency of up to 80 pulses per minute up and down inside the snail’s distended eyestalks.

The palpitating broodsacs have a single purpose: to draw the eye of a predatory bird. Although it has not been witnessed in the wild, studies in captivity show that birds find these eyestalks irresistible, perhaps because they mimic the motion of a delicious caterpillar. This is a textbook example of ‘aggressive mimicry’ – when an animal impersonates another species with the purpose of gaining an advantage.

Once inside the bird, the larvae pass through its gut and metamorphose into the adult form, called a distome. The distome attaches itself to the wall of the bird’s cloaca with a pair of suction discs. Here, the cling-on waits for others to join it so it can mate and lay eggs to be distributed in the bird’s droppings, completing the circuit when devoured by an unsuspecting snail.

The name fluke comes from the old English for the fish flounder – areference to the flattened profile of both species

LOOK CLOSER

Regeneration game

It has been noted that when birds strike parasitised snails, they mostly snatch the eyestalks. Many species of snail are able to regrow them, so it’s possible that the green-banded broodsac is the perfect polite parasite, leaving its host to wander off to live, recover and potentially become a host another day.