New Frontiers

A groundbreaking tagging operation has just been completed in South Sudan. Marcus Westberg joins the team on the ground and in the air.

The Big Picture (above)

While conflict continues in the capital of its northern neighbour, South Sudan is making history for more positive reasons. An epic GPS collaring operation has just concluded in Boma and Badingilo National Parks, both of which recently came under the stewardship of African Parks, in partnership with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism. Until now, little has been known about South Sudan’s wildlife, a result of decades of civil unrest that only ended in 2020. The data from the collars and from aerial surveys will reveal how animals move through the landscape, and in turn, inform conservation.

Eye in the sky

A spotter plane locates a herd of tiang antelope. South Sudan hosts a spectaclar seasonal antelope migration, with four species (white-eared kob, tiang, mongalla gazelle and bohor reedbuck) travelling across the landscape in their hundreds of thousands. It’s long been considered the second-largest land migration in Africa after the Serengeti wildebeest, but could actually be the largest.

Purple haze

A storm darkens the skies over Boma National Park. Both Boma and Badingilo support not only wildlife, but also significant human populations. Conservation will thus involve close work with local communities alongside ranger training and improvements to infrastructure – currently, much of the region is only accessible on foot or by air.

Out in the open

A leopard patrols open ground in Badingilo. This area was once renowned for large mammals, but decades of war have taken their toll. Yet, while species such as zebra and black rhino have been hunted to local extinction, many others have clung on. Alongside large herds of antelope, leopards, elephants and Nubian giraffes still roam, and the team even discovered a healthy cheetah population, a species not sighted in this landscape for years.

Cooling off

Elephant populations in South Sudan have plummeted from an estimated 80,000 in the 1980s to fewer than 5,000 today, a result of poaching for the ivory trade. This bull is one of five elephants collared in Boma-Badingilo, in the capable hands of wildlife vets Richard Harvey and Sara Ferguson. With temperatures exceeding 30˚C, heat stress is a serious risk. The vets work quickly, keeping the animal cool using jerrycans of water.

Sleeping giant

As part of outreach work, two Jie chiefs from Boma’s Kassangor community were invited to a collaring day. “They had never been this close to a live elephant before,” recalls Marcus, “and were fascinated by how warm its trunk was.”

Eye of the needle

Additional veterinary treatment can be administered during the collaring process. This elephant, for example, was found to have sustained a bullet wound, which was flushed out and cleaned before its collar was fitted.

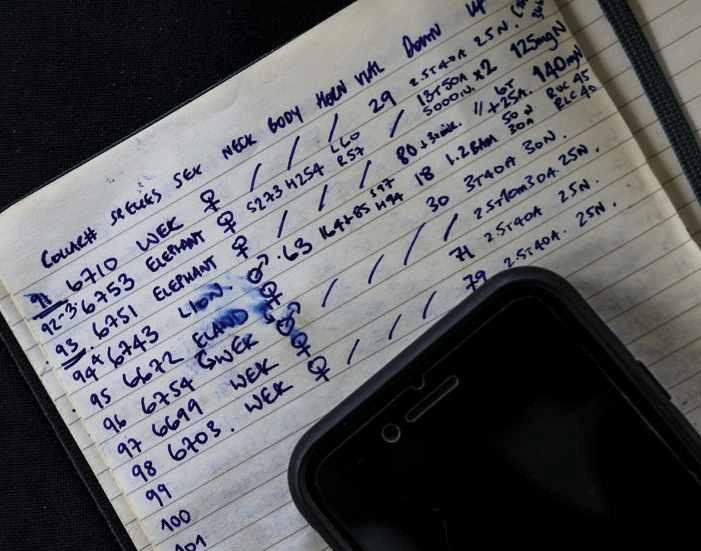

Taking notes

Detailed records are kept as each collar is fitted. This operation saw an impressive 126 individuals from 12 species tagged, selected from across the entire ecosystem to give a comprehensive picture of migratory routes. The collars send out a GPS location at regular intervals and will be continuously monitored through the seasons.

Not a pushover

A darted elephant may simply adopt an upright position as the sedative takes hold. In the event of this happening, there is only one way to encourage it to lie down on its side: give it a firm push.

Big birds

The Boma-Badingilo ecosystem is home to both common and Somali ostriches (the latter was declared a subspecies in 2016). Regional population sizes of these enormous birds – the largest in the world – are still unknown.

Falling tall

The Nubian giraffe is a Critically Endangered and little-studied subspecies of giraffe that numbers just 450 in South Sudan and 3,000 across Africa. This individual – one of 11 collared – has fallen in a slightly awkward position. Richard and Sara make it safe and comfortable before attaching a tag.

Counting cats

Almost no data exists for Boma-Badingilo’s predator populations, and it is not known whether they move with the migrating antelope. The opportunity to collar four lions and two cheetahs, and collect blood and DNA samples, was an unexpected bonus.

Peaks and troughs

To the east, the landscape of Boma becomes increasingly mountainous and rugged. Covering 19,189km2, Boma is the larger of the two parks (Badingilo comprises 8,935km2). Both form part of a significantly larger ecosystem.

Collaring the kob

A male white-eared kob was the 126th and final animal to be collared. Not much is known about this impala-like species, but it is thought to be among the continent’s more numerous antelopes. There could be millions of them in the Boma-Badingilo ecosystem.

Pulling weight

A second Nubian giraffe is tagged. A ranger assists Richard and Sara by placing his weight on the animal’s neck as the device is attached to its ear. Tagging large animals such as giraffes and elephants is immensely challenging, and perhaps indicative of what lies ahead for African Parks if South Sudan is to fulfil its potential of becoming a premier wildlife destination. “The potential for conservation at scale across this region is huge, but so too are the challenges,” says Marcus “The hope is that wildlife and people can prosper together.”

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Marcus is an award-winning photojournalist from Sweden whose work focuses primarily on conservation in sub-Saharan Africa. See more of his images at: marcuswestberg.photo