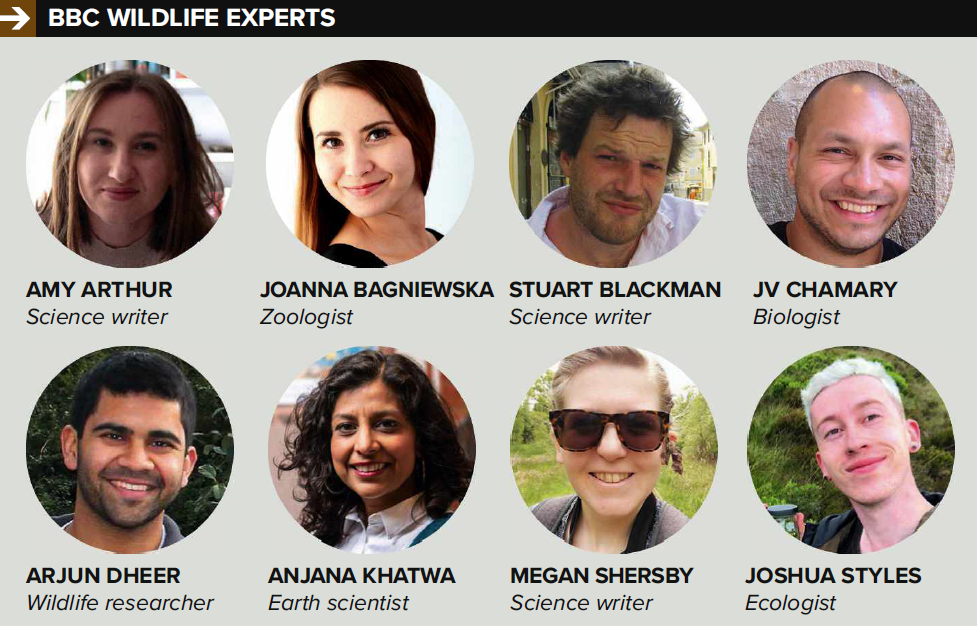

Q & A

Email your questions to wildquestions@immediate.co.uk

Can common toads climb trees?

AMY ARTHUR ANSWERS

Surprisingly, yes! While we usually think of toads as slow and lumbering animals, it appears they’re capable of climbing to great heights. A recent study of nest boxes and tree cavities in Britain found 50 common toads sitting comfortably up in the trees, with one as high as 3m above ground. A toad’s arboreal adventures are probably much more frequent than you might imagine, given that the same study recorded 94 blue tits, a common sight on tree branches.

It’s thought that toads use their fingers and toes to grip onto the tree bark as they climb, and they’re able to scale relatively flat, large trunks as well as small, near-vertical trees. Why they’d want to go through the effort of climbing, researchers aren’t sure, but it could be to escape their non-climbing predators, such as the barred grass snake. It may also offer new opportunities for catching prey, with a toad’s favourite food – live insects – in abundance.

How do dandelions propagate?

JOSHUA STYLES ANSWERS

We often think of plants as inanimate, lifeless objects in the landscape, when that couldn’t be further from the truth. Plants are vibrant, living, breathing creatures, forever finding ways to get the edge on their competition and avoid predation.

In order to attract as many pollinators as possible, dandelions throw their flowers high into the air during spring, but when flowering is finished and seeds begin to develop inside the old flowering head, this presents a problem. Developing dandelion seeds are a favourite spring foodstuff for lots of birds – especially finches, which will pry open flowering heads.

So once a dandelion has flowered, to avoid voracious predators, its stem will go limp and hug the ground to keep developing seeds out of sight. Only when the seeds are ripe do they throw up their stems, exposing seeds to the next gust of wind that will aid their dispersal. Isn’t nature incredible?

Can some vertebrates reproduce without males?

JOANNA BAGNIEWSKA ANSWERS

While we tend to associate vertebrates with a rather traditional mode of reproduction – mum and dad mating to produce young – some animals seem to believe that fathers are an unnecessary folly. More than 80 or so vertebrate species are happy to forsake males altogether, opting for one of three unisexual approaches.

Firstly, there’s parthenogenesis. This is when females produce eggs that develop without fertilisation. Also known as ‘virgin birth’, this mode is used by, among others, certain sharks, geckos, and Komodo dragons. Secondly, there’s gynogenesis, which is very similar to parthenogenesis, but this time a sperm cell is needed to activate egg development. Gynogenetic mole salamanders resort to stealing sperm from males of related species; they use it to kick-start their egg production, and then discard it. Finally, hybridogenesis is when an egg is fertilised, but male genes are not passed on to subsequent generations. It’s seen, for instance, in water frogs and some fish.

All in all, unisexual vertebrates take girl power to a new dimension.

Are there any sociable worms?

STUART BLACKMAN ANSWERS

The word ‘worm’ covers a disparate array of invertebrates that are grouped together informally on the basis of their elongated, limbless bodies. Earthworms, roundworms, flatworms and ribbon worms, for example, belong to separate phyla, which means they are more distantly related to each other than we are to sea squirts.

They are generally not sociable, coming together only to mate and at food sources. Courtship is usually pretty minimal and there is little in the way of parental care.

That said, there is at least one spectacular exception. A group of parasitic flukes – atype of flatworm – form colonies of clones within the bodies of their snail hosts and have evolved a system of division of labour comparable to that of ants, bees and other social insects. Some individuals specialise in reproduction, while others become soldiers, devoting their existence to defending the colony from attack by other animals living within the snail.

Can a dinosaur be mummified?

ANJANA KHATWA ANSWERS

Ancient reptile skeletons are the hallmark of any natural history museum gallery. Devoid of flesh or skin, which rotted away or was eaten by scavengers, these fossil specimens continue to inspire and provoke ideas about how life existed on Earth hundreds of millions of years ago.

In rare cases, soft tissue and even dinosaur skin has been found to survive the fossilisation process. Rapid burial of these dead creatures can lead to mineral concretions building up around biomolecules, protecting them from complete disintegration.

However, a dinosaur fossil complete with fossilised skin found in North Dakota suggests another process might be at play: mummification. Open wounds and bite marks found on the skin suggest that the carcass was scavenged long before it became buried under layers of sediment. Its bodily fluids leaked out, enabling the skin to dry, ensuring its preservation during the fossilisation process, to create a mummified dinosaur.

RECORD BREAKER!

What’s the highest flying bird?

In 1973, a commercial aircraft struck a bird at 11,300m over West Africa. Feathers lodged in the engine identified it as a Rüppell’s vulture, a Critically Endangered species that has since been shown to possess a form of haemoglobin in its blood that binds exceptionally efficiently with oxygen. This record stands, even now we can track flight paths in detail using radioand satellite-tags. Stuart Blackman

FACT.

Chimpanzees are able to learn basic human sign language. Washoe, a captive female chimpanzee, was able to learn American Sign Language (ASL), with a vocabulary of 350 words.

All becomes clear

WHAT ON EARTH?

Is there any spectacle in nature more wondrous or downright mind-boggling than insect metamorphosis? The technical challenge of transforming a gluttonous caterpillar into a glorious butterfly is undertaken during the pupal stage. For weeks, this monarch chrysalis has hung serenely amongst the foliage with little outward sign of the frantic overhaul going on behind the scenes. With the refit almost complete and just hours left until emergence, the pupal skin has pulled away from the living tissues within and become translucent, providing a tantalising promise of what is about to be. SB

FAST ANSWERS

Are hyenas more closely related to cats or dogs?

Within the Carnivora order, the hyena family, Hyaenidae, falls under the ‘catlike’ suborder Feliformia, in contrast to the ‘dog-like’ suborder Caniformia, so they are more closely related to cats than dogs, but are closer still to civets and mongooses. Within Hyaenidae, there are two main clades: the ‘bonecrushing’ hyenas (which include today’s brown, spotted and striped hyenas) and the once-abundant ‘dog-like’ hyenas (which include today’s aardwolf, the only member of the subfamily Protelinae). AD

Can fungi be used to make clothing?

Biofabrication of fungi in a lab involves the growth and harvesting of mycelium. Designers and companies such as Stella McCartney, Aniela Hoitink, Suzanne Lee and Adidas have been experimenting with mycelium to make clothing, shoes and accessories. MS

Do all UK deer have antlers?

Of the six wild deer species living in the UK countryside, only five grow antlers. The exception is the Chinese water deer. In fact, the species’ scientific name inermis means ‘defenceless’ or ‘unarmed’. But the male (buck) and female (doe) do have tusks, enlarged canine teeth protruding downwards from the upper jaw, with the males using them, like antlers, to display and fight. MS

INSTANT EXPERT

Sleep: a mysterious state of behaviour

WITH EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGIST JV CHAMARY

The function of sleep is one of biology’s biggest mysteries. Being unconscious leaves an animal vulnerable to predators and leads to missed opportunities for activities such as foraging or mating. And yet all animals with a nervous system seem to engage in some form of sleep, meaning the benefits clearly outweigh the costs.

What is sleep?

It’s a behavioural state in which an animal is less alert to its environment. During sleep, a stimulus (such as a loud noise) that would prompt a rapid reaction while awake, must be more intense to provoke a response. Unlike other resting states, such as hibernation or torpor, sleeping animals wake up rapidly when stimulated.

The physiological features, timing and duration of sleep vary across the animal kingdom. Some species adopt a stereotypical posture while sleeping – humans lie flat and bats hang upside down – but in other creatures, sleeping postures can be subtle. Octopuses have ‘active sleep’, when their skin shifts in colour and texture, for example, and ‘quiet sleep’, when their eyes and tentacles move more slowly. Mammals and birds have two distinct states, too, called REM and NREM sleep.

So what’s the difference between REM and NREM sleep?

Rapid-eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) define sleep based on brainwaves, or oscillations across the central nervous system, captured in electroencephalogram (EEG) readings. The waves are quick and chaotic during REM (along with eye twitches – hence the name) but slow and synchronised in NREM. Electrical activity during REM resembles what’s seen in animals that are awake, so it’s also called ‘paradoxical sleep’.

Because body and brain temperatures drop during NREM, one explanation for REM’s function is that it’s like the brain is ‘shivering’ to keep warm. Indeed, large mammals, whose mass can better retain heat, spend less time in REM than small ones. Sleep also paralyses most muscles so we don’t normally act out our dreams.

Do animals dream?

Dreaming occurs during REM sleep and is captured by EEGs. A dream is a series of images, thoughts and emotions that the brain turns into a story. We may never know whether other animals experience dreams as stories, but they do include past events. In zebra finches, brain activity during the day matches readings at night, meaning they replay and learn songs while they’re asleep.

Meanwhile, the activity in the brains of rats sleeping after navigating a maze suggests they re-run the maze in their sleep.

Why do animals sleep?

Ah, this is the big mystery! There are three general theories, two involving the brain. The first theory is that shutdown enables restoration and detoxification, producing molecules and removing waste products. The second is that sleep improves cognitive performance by providing a period in which the brain can reinforce or prune synaptic connections among its neurones – to help with learning and memory without being confused by fresh sensory information.

The third theory, not involving the brain, is that sleep saves energy. Animals must balance a need to find food with spending energy to forage. This is shaped by their ecological niche – small mammals may have only a short window to hunt insects, whereas large herbivores gain few calories from vegetation. That may explain why the little brown bat snoozes for 20 hours a day, while an African bush elephant sleeps just two hours in the wild.

The three theories for sleep’s function aren’t mutually exclusive, and all have weaknesses. Even brainless jellyfish sleep, and you’d expect intelligent elephants – who famously never forget – to sleep longer.

Can we survive without sleep?

Yes, but not indefinitely! Sleep deprivation is ultimately lethal, can cause poor cognition, abnormal development and reduced lifespan.

But though sleep typically involves physical inactivity, certain species have evolved a way to stay safe, by shutting off one of their two hemispheres. Such ‘unihemispheric’ or half-brain sleep is found in whales, dolphins, fur seals and great frigatebirds, among others, which all keep one eye open to watch for predators and potential dangers while swimming or flying.