Islands of adventure

If you crave a remote island paradise but don’t want to fly, there are white-sand beaches and extraordinary wildlife a ferry ride from Cornwall

IT’S A GLORIOUSLY WARM Tuesday in June when the Scillonian III draws into the pretty harbour on St Mary’s, the largest of the Isles of Scilly, announcing her arrival with three ear-splitting honks. It’s fitting that it’s a blue-sky day, as these are often referred to as the Sunshine Isles, basking as they do in the restorative warmth of the Gulf Stream.

It doesn’t take long to see why they say Scilly is special. The archipelago lies just 50km from Penzance, yet feels as if it has casually shrugged off its British identity. Its white sands and sparkling waters feel more akin to the Caribbean; its fusion of subtropical and native plant life feels a world away from the green and pleasant land a short hop back over the water.

For what is essentially a smattering of granite cast out in the Atlantic, Scilly punches far above its weight for wildlife, a quality reflected in its formidable tally of designations. It’s a Heritage Coast and a Special Area of Conservation, and claims the title of Britain’s smallest AONB. It contains numerous Ramsar wetland sites and Special Protection Areas, and its 11 Marine Conservation Zones are trumped by 26 SSSIs. Not too shabby for a land area of just 16km2, roughly half the size of Bath.

SCILLY IS BEST KNOWN FOR ITS birds, with a list topping 453 species at the last count, more than any single site in Europe. It hosts a nationally and internationally important assemblage of breeding seabirds that includes storm petrels, puffins, razorbills and shags. And, as England’s gateway to the Atlantic and our most south-westerly point, the islands offer the first (and last) landfall for migrants making their spring and autumn passage across the ocean – and for any lost souls whisked away by the wind. “‘First seen in Scilly’ is an all-too-common note against many of the UK’s rarest vagrant birds,” writes BBC film-maker Andrew Cooper in his book Secret Nature of The Isles of Scilly. It’s a trend that continues apace: only in October did a Blackburnian warbler make its England debut on Bryher, blown off-course while travelling down the Americas.

“For what is essentially a smattering of granite cast out in the Atlantic, Scilly punches above its weight”

My visit falls between migration seasons, but there is still plenty to see – or not to see, as it happens. Joining naturalist Will Wagstaff on a nature walk around Tresco, I discover that Scilly is equally interesting for what it doesn’t have. “There are plenty of song thrushes and sparrows here, which are declining on the mainland, but you won’t see a nuthatch or green woodpecker,” he says, as we follow the path from New Grimsby Harbour to Great Pool, a groundfed freshwater lake that roughly divides the island in half. “No jays have been seen here in 40 years and jackdaws are rare. Somebody once chartered a boat to see a magpie.”

It’s the same with insects. The bluetailed is Scilly’s only damselfly, and just 11 of Britain’s 59 butterfly species are resident. “We have no orange-tips or brimstones,” says Will, pointing out two speckled woods battling for territory, rising in an angry spiral. “But if it migrates, we’ll get it – we often see monarchs from the USA.”

WILL HAS SUPER SENSES, frequently interrupting his own commentary to pick out songs and calls from the surrounding chorus. The wren – Scilly’s most common bird, with 2,500-5,000 pairs – is the one we hear the most. “If in doubt, say ‘wren’, and there’s a 9 out of 10 chance you’ll be right,” he says. With peregrines the only resident raptors, these diminutive birds can afford to sing brazenly from their perches, “cheating onlookers by holding their tails down rather than aloft”.

By the end of the two-hour ramble, we’ve heard or seen, to name a mere few, chaffinches, wrens, dunnocks, starlings, blackcaps, reed warblers, meadow pipits, linnets, pochards and herons, all with frankly minimal effort, testament to the confiding nature of Scilly’s birdlife. An unexpected surprise is a hobby, hawking against the blue sky, scattering the swifts and swallows.

“Just when I see a patch of vegetation that vaguely resembles home, a profusion of exotics comes into view”

Exploring Great Pool and its neighbour, Abbey Pool (ideal spots to spy summer stragglers and the first winter visitors), I can’t decide whether I’m in Cornwall, the Med, Jamaica or somewhere else entirely. Just when I see a patch of vegetation that vaguely resembles home, a profusion of exotics comes into view. Horse chestnuts stand with Chilean myrtles, swathes of ivy give way to giant ferns, and fabulous succulents explode from stone walls. “Don’t trust the botany here,” warns Will, as we feel the papery leaves of New Zealand’s muttonbird tree, flanked by an imposing 3m-tall trio of purple echiums from the Canaries and a sprawling, showy gunnera.

But it’s in the world-famous Abbey Garden where the plant life really takes your breath away. Nestled around the ruins of a 12th-century priory, this subtropical spectacular was the handiwork of Augustus Smith, who took over the lease of the islands from the Duchy of Cornwall in 1834. Smith knew the mild climate would lend itself to warmth-loving plants, if only he could fashion a shelter belt – a windbreak of trees and shrubs – as a defence against the brutal storms that barrel in from the Atlantic each winter. With no British tree capable of tolerating seasonal lashings of salt-laden wind and spray, Smith turned to California’s robust and fast-growing Monterey pine and cypress to take one for the team.

As these trees took root, so did a microclimate, and with it a startlingly beautiful garden. Wandering the vast, rectangular maze of paths, surrounded by explosions of more than 3,500 luxuriant plant species from across the globe, a sculpture or other arty objet around every corner, I feel like I’ve disappeared into a dreamy, tropical paradise. The gardens even come complete with golden pheasants and, better still, red squirrels, which are now thriving here following introductions in 2012 and 2013.

THE SULTRY STILLNESS OF THE gardens rapidly dissolves when I take to the water. The sun has disappeared behind a low bank of cloud and a stiff breeze is whipping up a gentle swell. I’m heading out to the Western Rocks on a seabird safari with ecologist Vickie Heaney, and plain sailing this is not. Scilly’s seas are bespattered with rocky outcrops, islets, stacks and stumps, and beneath the surface lurk all manner of treacherous reefs and shelves primed to tear even the largest of vessels to shreds. Little wonder there are said to be more shipwrecks per square mile here than anywhere else on Earth. Cruising past a bustling raft of at least 200 gannets, puffins, razorbills and black-backed gulls, we reach Bishop’s Rock Lighthouse, a desolate tower presiding over the foaming surf. The skipper switches the engine off and we bob for a spell on the bumpy water.

Landing on the Western Rocks is difficult and discouraged, so this outlying seascape has been claimed in no uncertain terms by wildlife. Atlantic grey seals eyeball us lazily from isolated haul-out spots, their relaxed demeanour belying the fact that they are a globally rare species. Shags stand proud on impossibly sharp pinnacles, their wings spread out to dry. A small pod of common dolphins puts on a brief show and a sunfish potters by. There are shouts of excitement as a fellow passenger glimpses a broad, grey back slicing the surface: could that possibly have been a minke whale?

“There’s a brief pause and then the noise comes back. We’re in conversation with a Manx shearwater.”

Back on dry land, there’s one more seabird I’m keen to encounter. Manx shearwaters are summer visitors to the UK, arriving in early spring from South America to breed on offshore islands. By day, they secrete themselves away in underground burrows, safe from predators such as greater black-backed gulls; by night, they gather in large flocks to feed on the water, throwing out their unearthly calls as they return to the shore. Only a handful of other UK islands, including Rum and Skomer, host breeding colonies, together equating to 80 per cent of the world’s breeding population.

MANX SHEARWATERS HAVE not had an easy ride. Populations have plummeted due to predation from rats, who make easy pickings of vulnerable chicks cornered in burrows. By 2000, Scilly’s population was estimated at 200 or so pairs, with just 15-20 on St Agnes and Gugh. But the species’ fortunes have slowly reversed thanks to The Isles of Scilly Seabird Recovery Project, which facilitated the complete removal of rats from these islands over the winter of 2013-14.

“It’s been a real success, in large part because we had 100 per cent support from the local community,” says Vickie, who monitors the birds during the breeding season. “Numbers have at least quadrupled since the project began. In 2021, we had 55 chicks.”

Vickie surveys the burrows throughout the summer, and I spend a breezy morning in her company on St Agnes’ grassy shore. To determine if a bird is in residence, she plays a recording of a call from her phone. “They take this as a territorial challenge and call back,” she explains. We crouch at burrow number 10, marked by a small wooden stick, and hit ‘play’. A chaotic, peculiar squawking breaks the silence. There’s a brief pause and then the noise comes back from the depths of the burrow. We’re in conversation with a Manx shearwater.

In her 15 years on the project, Vickie has identified more than 80 burrows – and got to know them well. Particular favourites include Feisty Burrow, whose occupant emerges routinely to have a peck at her phone; Double Yoker Burrow, in which two females attempted to breed together, and The One Show Burrow, filmed for the BBC series in 2011.

St Agnes was selected for rat eradication thanks to the deep channel that separates it from its neighbours, making a ratty recolonisation less likely, but not impossible. Efforts will be ongoing if these highly intelligent rodents are to be prevented from staging a comeback. Signs urge you to “rat on a rat” and volunteers routinely check 55 bait stations dotted across the island for tell-tale teeth marks in chocolate-flavoured wax.

“Getting rid of the rats has been very beneficial,” says Sam Hicks, who runs Troytown Farm and Campsite and has four bait stations on his land. “We’re usually booked up anyway, but the increasing presence of Manx shearwaters makes guests’ experience more enriching. I’ve only ever had one person complain about the noise.”

Enriching is certainly how I’d describe my four days on the Isles of Scilly. I manage one last walk on St Mary’s before heading back to the quay to await the Scillonian III. But I have a feeling this won’t be the last time I hear those ear-splitting honks.

Sea safaris on the Scillonian III

Any wildlife adventure to Scilly starts from the top deck of the Scillonian III ferry. The crossing from Penzance to St Mary’s has just been named the UK’s highest diversity ferry route for wildlife spotting by marine conservation charity ORCA, whose scientists conduct surveys on ferry routes all around the UK and have been working from the Scillonian since 2009. Common dolphins (right) are frequently seen hurtling towards the ship to ride its bow wave (299 were recorded over 13 surveys in 2022), while rare behemoths such as basking sharks and fin and minke whales are always a tantalising possibility. Seabirds are easy to observe, with regular sightings of gannets, puffins, guillemots and razorbills, and even Manx shearwaters and storm petrels. Find out more about ORCA at orcaweb.org.uk.

SCILLY SPECIALS

Scilly shrew

Also known as the lesser white-toothed shrew, as it lacks the red-tipped teeth of its mainland cousins. It lives fast and hard, consuming its own bodyweight in food each day and producing up to four litters a year.

Least adder’s-tongue fern

A tiny rarity whose only UK site is Wingletang Down, St Agnes (it’s also found on Guernsey). It survives in the grazed sward here, thanks to gorse management.

Scilly bee

Alas, this subspecies of the moss carder bee, once widespread across the Isles of Scilly, has not been seen in a decade. Its final stronghold was the coastal heathland of St Agnes.

Dwarf pansy

No taller than 1cm, this exquisite little flower doesn’t grow on mainland Britain. It blooms from March to May on Bryher and Tresco. Recent conservation efforts have restored the plant to Teän island, after an absence of 17 years.

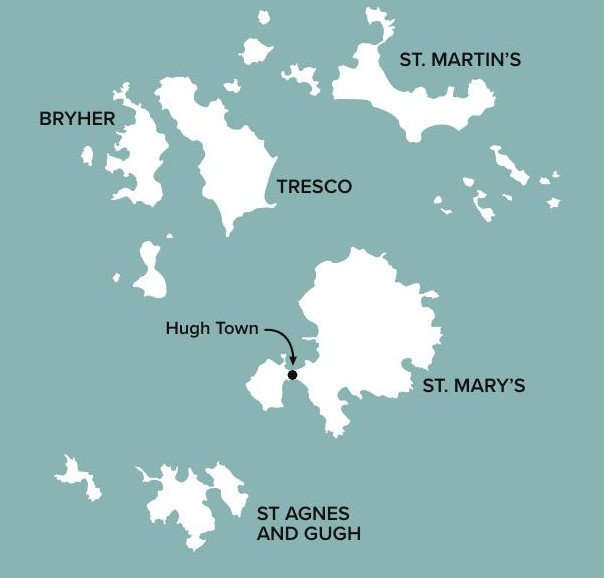

The Isles of Scilly

There are five inhabited islands on the Isles of Scilly: St Mary’s, Tresco, Bryher, St Martin’s, and St Agnes and Gugh, which are connected by a sandbar at low tide. St Mary’s is the largest and most populous.

HOW TO GET THERE

By ferry

Scillonian III sails from Penzance from March to November (2 hrs 45 mins). From £76.25.

By plane

The Skybus flies from Lands End (20 mins), Newquay (30 mins) and Exeter (60 mins). From £121.50.

By helicopter

From Penzance heliport (15 mins) to Tresco and St Mary’s. From £129.

Visit islesofscilly-travel.co.uk and penzancehelicopters.co.uk

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sarah is features editor at BBC Wildlife. She visited the islands courtesy of Isles of Scilly Travel and the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust.