Celebrate the wonder and variety of sharks, an ancient and much-misunderstood fish.

Before the Spielberg’s film Jaws was released in 1975, sharks were beautiful and fascinating fish. But the novel and film gave sharks an undeserved reputation as mindless man-eaters – but the truth is far more engaging.

Author Michael Bright celebrates the wonder and variety of these ancient, much-misunderstood fish.

34 amazing shark facts

1. How long have sharks been around?

Fossils of sharks are rare – their cartilaginous skeletons do not preserve well. In fact, the oldest specimens comprise little more than teeth or tiny scales found in 460-million-year-old rocks.

So when a fossil shark skeleton was discovered at a site in New Brunswick, Canada, in 2003, it was greeted with great excitement.

Scientists named it Doliodus problematicus, meaning ‘problematic deceiver, and estimated that it was about 409 million years old, making it the oldest intact shark fossil ever found. The species would have resembled the modern bottom-dwelling angel shark, with the addition of a long spine on each pectoral fin. It also had replaceable rows of teeth, a feature of modern species that was previously thought to have been absent in the earliest sharks.

2. How embryo bamboo sharks evade detection

When a predator approaches a bamboo shark in an egg case, the embryo detects the intruder using electro-receptors in its snout. The shark stops breathing and remains motionless until the danger has passed.

3. The remarkable lifecycle of the lemon shark

A lemon shark will return to its place of birth to give birth itself, even after several years away. Research at the Sharklab in the Bahamas has revealed most of the lemon shark’s life-cycle.

Newborn pups head for mangroves in a lagoon on Bimini, where each patrols a small territory.

During the next five years, it stays in the lagoon with sharks of the same size, watching and learning different behaviours. For example, if a foraging shark adopts tight turns as a feeding strategy, others will follow suit shortly afterwards.

When they are about five years old the sharks head out of the lagoon, though many linger close to the island until they reach maturity.

4. When were megamouth sharks discovered?

The megamouth is one of only three plankton-eating sharks, the others being the whale shark and the basking shark.

Megamouth was the biggest wildlife surprise of the 20th century. This flabby-finned, cavernous-mouthed, rubber-lipped, filter-feeding shark was discovered off Hawaii in 1976. Since then, a further 55 have been reported. It grows to 5.5m long and follows the daily vertical plankton migration between the surface and deep

5. How the thresher shark uses it tail to catch prey

The thresher shark thwacks its prey with its extraordinarily long, scythe-shaped tail. Film from Pescador Island in the Philippines depicts a thresher heading for a shoal of sardines; it stalls, dips its nose and brings its tail over its back like a bullwhip, stunning several fish with a single swipe.

6. How big are newborn great white shark pups?

The smallest-measured great white shark was an 85cm-long newborn pup weighing 12kg, caught in Edremit Bay on Turkey’s west coast in July 2011.

Catches of other young pups in the area, some not more than four days old, indicate that the eastern Aegean Sea is probably an important great white nursery. Other nursery areas in the Mediterranean include the Sicilian Channel south of Lampedusa and the eastern Adriatic Sea.

7. Which shark is the best sniffer?

The nostrils of pelagic sharks such as the oceanic whitetip are higher on the snout than those of bottom dwellers.

This observation has led Russian researchers to suggest that this species pokes its snout out of the water to capture air bubbles carrying wind-borne odours. The bubbles break up in the nostrils, where sensory cells lining the nasal cavity pick up the released smell.

If true, this could explain how these sharks appear more quickly at food sources than could be expected by simply following scent slicks in the water.

8. What’s the slowest shark?

The 5m-long Greenland (or sleeper) shark is the world’s slowest-swimming shark species. It was long thought to scavenge dead seals, but recent research from Norway indicates that it takes live ones, too, despite a top speed of just 2.5kph – it catches them by sneaking up under the ice while they sleep.

It also eats fish, which might be attracted to luminous parasitic copepods usually attached to the cornea of the shark’s eyes. That might explain how this slowcoach catches fast-swimming cod and herring.

9. The world’s largest fish and most mysterious

At up to 14m long, the whale shark is the world’s largest living fish. It is also mysterious, migrating vast distances and diving to depths of 2,000m. But its secrets are now being unlocked.

A pregnant female was studied carrying embryos that ranged from recently fertilised to near-term, all with the same father; this suggests that female sharks mate only once, storing sperm to fertilise their eggs at later dates. Finding confirmation is difficult, because mature females are rarely seen; at coastal feeding sites, male:female bias is 72 per cent.

Another study may have identified a nursery site in the tropical Atlantic. A tagged female was tracked as she swam 8,000km in 150 days from a feeding site off Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula to the mid-Atlantic, where it is suspected she gave birth.

10. Is there really a shark that walks?

Australia’s epaulette shark walks on its paddle-shaped fins both in and out of the water. It can also swim to make a fast getaway, but as often as not it gets about by clambering over the seabed.

11. The glowing shark

The dorsal fins of the deep-sea velvet belly lanternshark bear spines that are illuminated by light organs at their base, resembling the lightsabers featured in the Star Wars films. They glow in the dark to warn

off potential predators.

12. Bull sharks can live in freshwater

Bull sharks have the physiological wherewithal to survive in fresh water: they have organs, including a rectal gland, kidneys, liver and gills, that regulate the salt and water balance in the body. Female bull sharks enter estuaries to drop their pups, and Australia’s Brisbane River is a known pupping site; every year, when the temperature rises, youngsters are seen leaping from the water and spinning

in the air – nobody knows why.

13. The shark that can swell up to twice its size

When threatened – usually by a hungry sealion or larger shark –the so-called swell shark cephaloscylum ventriosum, slips into a crevice and inflates its body like a rubber raft.Within seconds, the shark is twice its original size and wedged in place. And it is almost impossible to yank it out.

14. The living fossil shark

The deep-sea goblin shark is a fish unlike any other. It possesses an elongated, spade-shaped snout lined with electro-receptors, primitive nail-like teeth and highly protrusible jaws. Fossil specimens, dead ringers for the modern species, have been discovered in 125-million-year-old rocks, making the goblin

shark a good example of a ‘living fossil’.

14. The cookie-cutter shark

The cookie-cutter shark has the largest teeth of any shark relative to body size, and it uses them in an unusual way. It ascends from deep waters at night, a vertical migration of up to 3km, and hovers in the water column, with buoyancy provided by a large liver rich in low-density lipids. There it ambushes whales, dolphins, tuna and even people, latching onto them with suction-cup lips; it then takes circular bites using its teeth like a pastry cutter.

15. The shark best at camouflaging

The weird-looking wobbegong shark is a master of disguise and camouflage. Its name means ‘shaggy beard’ in an Australian Aboriginal language, a reference to the fringe of tassels around its snout. Together with its mottled colour, these help it blend in with its coral-reef background, safe from predators and ready to ambush any passing fish.

16. More like to be mauled by neighbour’s dog than bitten by shark

Though the results of a shark attack are often serious, you are more likely to be mauled by your neighbour’s dog than to become a victim of a shark attack. Clearly Jaws, its sequels and the media’s love of a good shark-related headline have done these species a severe public-relations disservice. According to the International Shark Attack File, 10 fatalities from 69 unprovoked attacks were reported worldwide during 2023. Since the 1900s such reports have increased, though this is probably due to better reporting and more people spending longer in the water.

17. What’s the fastest shark?

With bursts of speed reaching about 35kph, the shortfin mako is the world’s fastest shark. Its speed is enhanced by a heat-exchange circulatory system that keeps the swim muscles, stomach, brain and eyes at 5–11°C above the temperature of the surrounding seawater, giving it the edge when pursuing fast-swimming prey such as mackerel.

18. The weirdest egg case

The egg case of the horned shark is shaped like a wood screw. This enables the mother to wedge it firmly into cracks and crevices using her mouth, preventing it from drifting away.

19. Why are golden hammerheads – well golden?

Juvenile smalleye hammerhead sharks off Trinidad and in the Orinoco Estuary get their colour from their food. They are a vibrant orange-yellow hue and mainly eat shrimps coloured by carotenoid pigments, while adults – which are a pale yellow – mostly feed on sea catfish and their eggs.

20. Why hand feeding sharks is a no-no

Hand-feeding sharks might seem like it’s fun to watch, and merely provides a free meal to the predators, but research at Australia’s Osprey Reef indicates that it might actually be detrimental to their health. Whitetip reef sharks hunt at night and rest during the day. Feeding them during daylight deprives them of essential sleep.

21. How big is the bluntnose sixgill shark?

At up to 5.5m long, the bluntnose sixgill shark rivals the great white in size but, because it lives much deeper, little is known about it. Adult sixgills are solitary and are very possessive at large carcasses, such as whales that have drifted down from the surface.

From May to November, pregnant females pitch up in Norwegian fjords and the shallow waters of Puget Sound, Washington State, to give birth. A surprise observation, however, is that a mother’s litter does not disperse at random into the surrounding area, as most other sharks seem to do. Brothers and sisters leave mum, but travel about in family groups.

22. What’s the largest shark to have ever lived?

The largest shark that ever lived is Carcharodon (or Carcharocles) megalodon, a giant predator that became extinct 1.5 million years ago. It was up to 18m long and fed on whales.

It is known mainly from its triangular, serrated teeth, which can be 15cm long. Computer simulations suggest that it had a bite force of 11–18.6 tonnes, the greatest of any animal tested so far. By comparison, the bite of a modern great white is a puny 1.9 tonnes.

23. What’s so special about dusky shark mothers?

Dusky shark mothers bestow newborn offspring with supplies to help them survive their first few weeks. The pups have unusually large livers packed with stored oils to sustain them until they find suitable feeding grounds.

24. How does a grey reef shark repel intruders?

If approached too closely, a grey reef shark employs a warning display. It drops its pectoral fins, arches its back and swims erratically to say “Back off!” If the intruder persists, the shark attacks with a slashing bite.

25. Why unborn sand tiger sharks get eaten by each other

It’s a tough life being a sand tiger shark embryo, especially if you are not the biggest… Unborn sand tiger sharks indulge in intra-uterine cannibalism. In each branch of their mother’s uterine horns, the largest and best-developed embryo consumes its womb mates, so that only two pups are actually born.

26. What’s special about shark teeth?

Sharks have extremely good dental health. Their teeth are not only coated with fluoride (fluoroapatite), which is resistant to bacteria and acid attack, but are also endlessly replaced if they are knocked out.

Did you know a great white has about 30,000 teeth – but not all at the same time.

27. Why the sawshark is very aptly-named

The very aptly named sawshark detects fish and squid on or close to the seabed using two barbels and rows of electro-receptors on its saw. Anything it disturbs is sliced and diced with side-to-side swipes of its blade-like snout. The shark then doubles back to vacuum up the casualties.

We reckon it is also a dab-hand at DIY – and cleaning up after projects – although you wouldn’t want to get to close

28. What’s unique about a shark’s skin?

Shark skin is covered with tiny dermal denticles that channel water over the body in the most hydrodynamically efficient way. They also create small vortices close to the skin that reduce drag and help pull the shark along. With this arrangement sharks speed through the water 12 per cent faster than if they had smooth skin. The scales can also change angle by as much as 60 degrees. This ‘denticle bristling’ helps facilitate a fast turn.

29. The shark with added frills

The frilled shark is eel-shaped, with six pairs of frilly gill slits. It has the longest gestation period of any known vertebrate – up to three-and-a-half years – and lives down to 1,500m. It is thought to bend its body and lunge like a striking snake to capture its prey.

30. Where do basking sharks go in the winter?

One of shark biology’s abiding mysteries has been where basking sharks go in the winter, but tracking studies now reveal that some make for the sun. In the north-west Atlantic the world’s second-largest fish travels from New England to as far south as the mouth of the Amazon, while in the north-east Atlantic baskers have been tracked from Malin Head on the Irish coast to Senegal, a distance of 5,000km.

One fish, however, bucked the trend: in just 82 days it swam 9,589km from the Isle of Man to Newfoundland, and during its journey it dived down to a record depth of 1,264m. Basking sharks clearly have more surprises for us yet.

31. Why do hammerhead sharks have such strange heads?

Sporting a wide, flattened head that is uniquely shaped like a double-headed hammer, it’s not hard to see how hammerhead sharks got their name. The explanation behind the shape of the hammerhead’s head has long been debated. While undoubtedly giving the sharks extra lift, the ‘hammer’ – or cephalofoil, as it’s technically called – may also help them make sharper turns in the water.

The widely spaced eyes allow for effective stereoscopic vision, while the head’s broad shape also houses a sense organ known as the ampullae of Lorenzini. Packed with electroreceptors and operating like an underwater metal detector, it helps the sharks to detect prey hidden on or just under the sea-floor sediment.

32. What is the ‘ampullae of Lorenzini’?

Sharks have a battery of different sensors but the most remarkable must be the little pits on a shark’s snout. Known as ‘ampullae of Lorenzini’, they give the shark an ability to detect extremely weak electrical activity associated with contracting muscles in its prey. A hammerhead has these electro-receptors spread across the front of its broad head. So it sweeps the seafloor like a metal detector, and locates prey even when it is hidden below the sand. As long as the target’s heart is beating, it has nowhere to hide.

Mental maps and calendars guide tiger sharks. Throughout the Hawaiian Island chain they show the extraordinary ability to be at the right island at the right time, and they swim there taking direct pathways across the ocean. At French Frigate Shoals, in the extreme north-west, sharks turn up at just the moment that albatross chicks are fledging. The youngsters are not especially good flyers and often ditch in the sea where the sharks are waiting for them. While some tigers remain in the north-west and others head for deep water, many of the large pregnant females return to pupping sites close to Maui, O‘ahu and Big Island in the late summer and autumn. Their arrival coincides not only with humpback whale births, but also with what is statistically the greatest shark-bite risk for humans.

33. Why do female sharks have thicker skin than males?

Female sharks have thicker skins than males. This is because mating is a violent affair, with males grabbing females and hanging on with their extremely sharp teeth – hardly safe sex!

34. Female sharks can have so-called ‘virgin births’

Captive female blacktip, bonnethead and bamboo sharks have been recorded reproducing without males, a process known as parthenogenesis. This ability could be one reason sharks have been so successful.

- How many species of shark inhabit the seas around Britain?

- Blue shark facts: size, diet and what they look like

Discover more amazing facts about wildlife in BBC Wildlife Magazine.

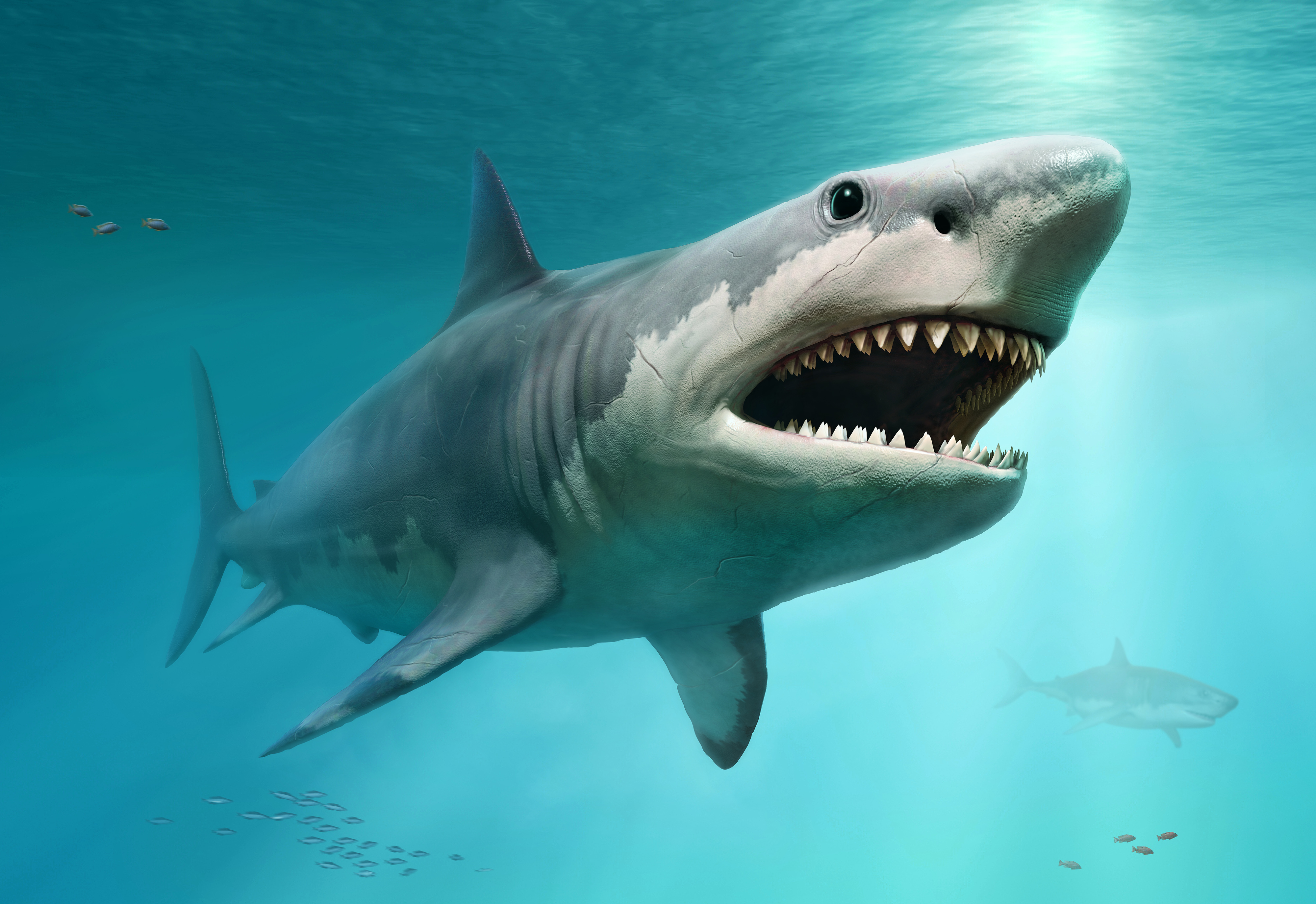

A great white shark photographed in Spencer Gulf (South Africa) © Alastair Pollock Photography/Getty Images