Hell or high water

The Paris-Roubaix Challenge pits amateurs against an abridged version of the iconic ‘Hell of the North’ race

Try to ride with a loose grip – your hands resting on the top of the handlebars or on the hoods.” Sportive Breaks’ guide Christophe Smekens is sharing his advice for tackling the notorious cobbled roads of Paris-Roubaix, but it’s already too little too late.

My hands are in bits after my first taste of pavé: the four- and five-star-difficulty sectors Camphin-en-Pévèle and Carrefour de l’Arbre. Blisters are bubbling on my bare palms, while the skin has broken in places, causing a shooting pain whatever grip I try on the ’bars. And this was just a 40km warm-up ride.

The anxiety that had been building in my stomach all week about riding the cobbles has somewhat dissipated though: they’re hard going but when they’re dry, if you enter with speed, they can be ground out in a big gear without too much trouble. Instead, I’m now worrying about how my hands are going to withstand the following day’s Paris-Roubaix Challenge: a sportive that follows the final 170km of the professional men’s route to Roubaix’s iconic velodrome, including all 30 of the race’s gruelling secteurs (cobbled sections).

Returning to my hotel room, I slather on some Sudocrem and rummage in my kit bag for anything that can provide padding to my palms. The only gloves I’ve brought from home are a pair of waterproof winter ones in case of bad weather. With a clear day and highs of 20°C forecast, they’re not ideal, but I’m left with no alternative.

Written in stone

One of the oldest organised races in the world, Paris-Roubaix has pitted hardy individuals against the cobbled farm roads of northern France since 1896. Regarded as one of, if not the, hardest race in the professional calendar, the Queen of the Classics’ 259.9km distance includes 50km of rough, almost unrideable pavé terrain that pushes competitors and their bikes to the limits. And if it’s wet, those same coarse, grapefruit-sized cubes turn into an ice rink, where one slip can spell the end of a season: it doesn’t have the nickname ‘A Sunday in Hell’ for nothing.

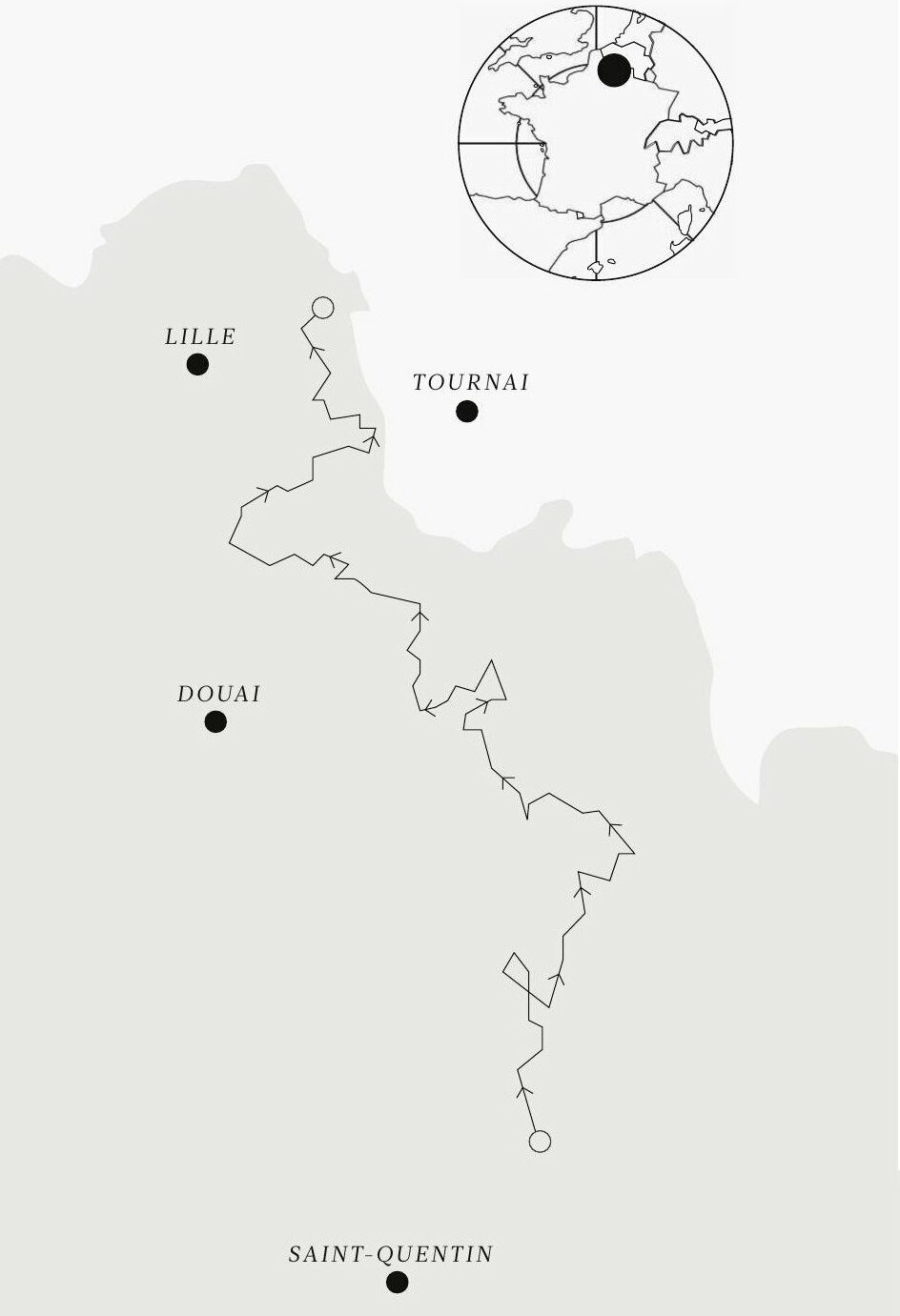

While it’s possible to ride the route at any time of year, amateurs have been able to get in on the action on the same weekend as the professionals since 2011 with the official Paris-Roubaix Challenge. The 13th edition comprised three distances: the Discovery (70km and eight cobbled sections), the Legendary (145km and 19 cobbled sections) and the Hell of the North (170km and 30 cobbled sections); the sportive offering participants a chance to test themselves on the course before watching elite athletes such as Mathieu van der Poel and Lotte Kopecky ride with mind-blowing speeds and huge amounts of skill over the same parcours.

Ever one for throwing myself headfirst into a challenge, I plump for the full-distance course. As the route will be used by the women’s race later that day, it involves a 4am wake-up call and a 90-minute coach transfer to be at the start line by 7am. There’s also a time cut-off in play that requires averaging 28km/h on the road and 14km/h on the cobblestones. I’m not too worried about the former and its relatively flat elevation gain, but it’s the pavé that has me concerned – particularly if my on-loan Scott Addict 20 succumbs to any mechanicals. Pumping the bike’s 32mm tyres up to 65 PSI, I sacrifice comfort and opt instead to reduce the risk of pinch punctures.

On the warpath

As we make our way south to the Busigny start line, there’s a nervous energy in the air on the coach; some riders try to catch up on sleep, while others engage in gallows humour about what lies in store. As dawn breaks, I catch glimpses of the First World War graves that line the roadside: a reminder of the area’s dark past, and the true reason for the race’s L’Enfer du Nord (Hell of the North) moniker. Although not comparable in any way with the horrors of over a century ago, it feels like we’re going into our own kind of battle as riders don their helmets and make last-minute checks of multitools, pumps and nutritional supplies.

Bunched into the start corral, blaring Europop reverberates off the buildings on the narrow street, ensuring that no one in a normally sleepy commune is getting their Saturday morning lie-in. After a compulsory countdown from dix, we’re off with a cheer, but it’s not long before the fanfare of the start is a distant memory, the hubbub replaced with an eerie silence that’s only broken by the whirring of hubs.

Settling into a rhythm, I think through my tactics for the ride. I plan to keep things easy on the road and approach each sector like an interval. As chain gangs whizz by, it’s hard not to chase their tail, but I need to reserve my energy for when it matters, most notably the three five-star-difficulty sectors; the first of which – the sheltered Forest of Arenberg – is almost 80km in. Even keeping things steady, I’m moving at a fair lick, and the first 10km of asphalt flies by in 20 minutes.

Entering the day’s first cobbles, Troisvilles à Inchy’s 2.2km three-star section, I shift into a bigger gear and remember Smekens’ advice. As the Schwalbe One tyres cross the threshold from the tarmac to the tough stuff, my blisters let out a whimper, but the gloves and my relaxed grip dampen the pain. I attempt to ride on the crown – more than a century of rubber-tyred traffic making this the ‘smoothest’ part of the ‘road’, but everyone else has the same idea and I’m soon caught in traffic. Keen to keep my time on the cobbles to a minimum, I take a rougher line to overtake. My hands aren’t happy and, going by the number of riders washed up with wheels removed on the side of the road, I’m increasing my chances of puncturing.

Reaching the end of the sector, my mind tricks me into thinking I’ve got a flat, but it’s just the contrasted smoothness of returning to the road. ‘Only 29 more secteurs to go’ I joke to myself.

The next two hours are a carbon copy of the first 10km. Rolling fields of rapeseed, its yellow bloom glistening under the early morning sun, are punctuated by quaint, one-road villages; an elderly woman watches from her first-floor window, a wry smile cast across her face from a lifetime of Paris-Roubaix going past her front door. The cobbles are also surprisingly bearable, particularly on ascents and descents where I can shift my body weight slightly backwards and gently guide the bars with my hands; a dropped chain is the only mechanical to report on.

And then I hit the deck. Halfway through Haveluy à Wallers’s four-star sector, pools of water on either side of the crown have turned the pavé into an oil slick. The whole road is soon a muddy slop and as riders in front slow to find the driest line, I pull on my brakes hard. My hire bike’s reversed European groupset means my instinctive tug locks the front wheel; it slides from beneath me, sending me diving over the handlebars. I somehow land on the verge, rider and bike mangled as one, my ego the only thing bruised. Dusting myself down, I calm my racing heart rate with deep breaths before remounting my bike. With the five-star Arenberg up next, I really don’t need any more adrenaline.

Although the first of the three most difficult sectors of the course, the Arenberg is arguably Paris-Roubaix’s most infamous. A straight, 2.3km tree-lined road that runs through the forested site of a former mine, there aren’t any corners for riders to contend with, but its grooved cobbles and the sizeable, uneven gaps between each one makes it near impossible to keep any momentum.

Approaching the sector, it isn’t clear if the Challenge course includes the chicane added to the men’s 2024 race in an attempt to increase safety and reduce entry speeds onto the cobbles. But I needn’t have worried as the open-road nature of the sportive means I’m brought to a literal standstill by a police officer directing traffic around the entrance to the popular spectator spot.

“Shifting into a higher gear, I try to keep the power consistent, but the terrain is doing its best to buck me out of the saddle”

With a short run-up to its start, any illusions of hitting the Arenberg at pace evaporate and I settle in for a slog. Slowing my cadence while shifting into a higher gear, I try to keep my power consistent, but the terrain is doing its best to buck me out of the saddle. Smekens wouldn’t approve but I hold onto the handlebars for dear life, desperate not to topple into the path of the passing riders on either side who are somehow gliding over the ruts. The towering trees that flank the trench make it seem like I’m riding towards the light, each cobble covered a pedal stroke closer to completing purgatory.

Reaching the tight left-hand corner that signals Arenberg’s end, a wave of confidence flows over me. I still have many sectors and a little under 90km to go, but nothing will be as difficult as what I’ve just overcome, and having sampled Carrefour de l’Arbre the day before, I know roughly what’s in store.

Pain is temporary

The cobbles come thick and fast. Caravans on the horizon are an indication that the next sector is imminent; each is soundtracked by a cacophony of whining boomboxes. A scoffed stroopwafel and a stock-up of energy gels at the Beuvry-la-Forêt feed stop is closely followed by the middle five-star sector – the 3km Mons-en-Pévèle – but by now the pitted tracks are melting into one giant rice crispy cake in my mind; the only thing differentiating them is the number on the banner as I exit telling me how many more sectors I’ve got to go.

“Crowds have started to gather on these potentially decisive cobbles ahead of the women’s race and they cheer on my efforts, but having the end in sight is all the motivation I need”

At Camphin-en-Pévèle, I’m on familiar terrain again and have a facsimile in my mind (and hands) of what’s left. Crowds have started to gather on these potentially decisive cobbles ahead of the women’s race and they cheer on my efforts, but having the end in sight is all the motivation I need.

I wince as I remove my gloves on the spin into Roubaix’s centre, worrying about what lies beneath. Yesterday’s blisters have burst, while there are new ones to add to my collection, but I remind myself that pain is temporary as I roll over the final, one-star Roubaix (Espace Charles Crupelandt) sector, moments from the velodrome. Riding around the banked track, any discomfort is overcome with a wave of achievement. Crossing the line, my 6:17 hour finish time won’t trouble the pros, but I’ve definitely won my personal battle with the Hell of the North.

LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

Getting there

● Roubaix is a 90min drive from Calais, making driving the easiest and cheapest option if you’re heading from the UK with your bike.

Eurostar runs regular services between London St Pancras and Lille, which is a short metro ride from the centre of Roubaix (bike spaces need to be booked well in advance). Brussels is the closest airport.

Where to stay

● The Mercure Lille Roubaix (mercure. accor.com) has double rooms (from £86 per night) and breakfast is £14. The hotel also has on-site storage for bikes and is a short ride from the Roubaix Velodrome.

Where to eat

● Brasserie Le Metropolitain on Av. Jean Lebas has good pre- and post-ride food options. It also has a wide selection of Belgian beers that are a perfect way to celebrate a hard day in the saddle.

2025 entry

● Next year’s Paris-Roubaix Challenge is on 12 April. Sportive Breaks have event packages from £469 (sportivebreaks.com).

Distance 170km Elevation 1,003m

Download the full route komoot.com/tour/1519091346