GUEST COLUMN

Queen’s stage

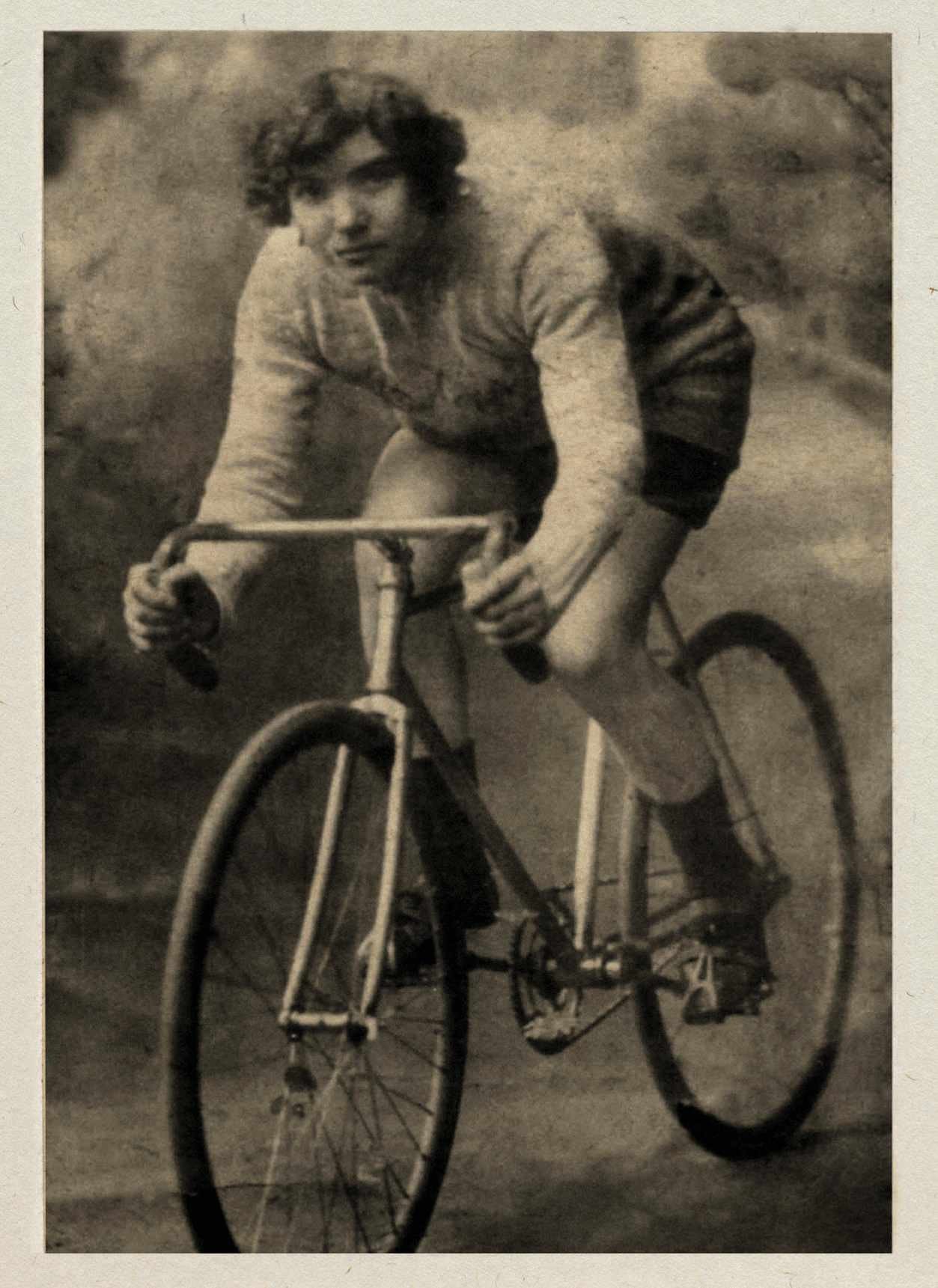

100 years ago, an Italian housewife rode – and completed – the Giro d’Italia. We recall the late, great Alfonsina Strada…

By 1924, money had begun to disfigure Italian cycling. Bike racing had always been a marriage between sport and commerce, but now the latter was contaminating both methodology and results. The issue, fundamentally, was that the trade teams had become just too powerful. Drafting was commonplace, the term gregario [support riders] had entered the lexicon and, worst of all, races were routinely bought and sold. Team riding was completely out of hand, and the bare-knuckled, man-on-man contests that had popularised the sport were increasingly rare.

The tail was wagging the dog, and fans were less than impressed. When the teams demanded appearance fees at the Giro d’Italia, race organiser Armando Cougnet dug his heels in. While it would be preferable to have the champions Girardengo, Bottecchia and Brunero at the race, a line needed to be drawn. Their absence would impact sales and advertising revenues at the Gazzetta dello Sport, the newspaper that organised the race, but Cougnet reasoned that they’d soon come scuttling back. The Giro was nothing if not a giant shop window, and the teams of Bianchi, Atala and Legnano were engaged in a perpetual tug-of-war for column inches and exposure. In the short term at least, the Giro was big enough and popular enough to survive without them. Wasn’t it?

The Giro, then, would be a race for individuals. Everyone would start on an equal footing, and the Gazzetta would provide board, lodge and a neutral service capability of sorts. The event would herald a return to old-fashioned behaviours and values. The Giro would be every man for himself, or, in the case of rider number 72, every woman…

The second of 10 siblings born into grinding poverty near Modena in northern Italy, Alfonsina Morini had been given an old clunker of a bike as a child. She’d started racing it because she liked it, and because she was unusually strong. Overwhelmingly, though, she raced it because there was no rule that forbade it. The very notion that a female might want to compete hadn’t appealed to the men in suits, so they hadn’t thought to proscribe it. Aged 16 she’d moved to Turin, the epicentre of Italian racing, and acquired a license. She’d mucked in with the city’s boy racers, broken the women’s hour record, and become something of a sporting cause célèbre. She’d then married a mechanic, one Luigi Strada, and moved to Milan. She’d begun to race semi-professionally, and evidently been very good at it.

In 1917, 26-year-old Alfonsina Strada had knocked on Cougnet’s door. She’d insisted he let her ride the Tour of Lombardy, and he’d acquiesced. Amidst general astonishment she was one of only 29 to make it round, and she did the same the following year. Thereafter she’d competed only sporadically as she worked as a seamstress, and tended to her husband’s failing mental health.

Now, however, Luigi Strada had been committed to an asylum, and she had urgent need of money. Cougnet’s ailing Giro needed all the help it could get, so he took a gamble. Alfonsina would be permitted to participate, albeit without great fanfare. Cougnet couldn’t afford for her inclusion to render the race ridiculous in the eyes of sporting purists, but he had a hunch it might just work. Alfonsina Strada was one of the toughest, most courageous racing cyclists he’d ever known. If – and it was a big if – she had it within her to complete 3,613km over 12 biblical stages, it would likely constitute a decent sub-plot. If, on the other hand, she wasn’t up to it, she’d slip quietly away from the race and let the rest get on with it. And so it was that, in the early hours of 10 May 1924, Alfonsina Strada took to the start of the Giro d’Italia.

The rest, as they say, is history. When La Gazzetta reported that she’d survived the opening stage (300km from Milan to Genoa) the Italian public had eyes only for her. They showered her with money, gifts and adulation. When she arrived over the time limit on stage eight, the clamour to see her was such that they allowed her (some say urged her) to carry on regardless. By then she was utterly exhausted but, outside the official classification or otherwise, she kept on keeping on. Somehow she finished the enormous 415km 10th stage, from Bologna to Rijeka, in just over 21 hours, and now even the sceptics were won over. Four days later she rolled into Milan to the mother of all standing ovations, and to Italian sporting immortality.

Herbie Sykes

Journalist and author

Herbie writes about professional cycling and football. His books include Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia