We spoke to Dr Xavier Disley and Dan Bigham to find out why some teams use waxed chains and why others don’t

Chain waxing has grown steadily in popularity in recent years, with more brands than ever now offering wax-based chain lubricants.

Proponents of immersively waxed chains – myself included – often point to data from independent tests showing wax-based chain lubricants to be among the most efficient available, and tout their ability to resist wear-inducing contamination.

Though the hassle involved is enough to put off many everyday cyclists, you might think WorldTour teams, competing at the top of the sport at races such as the Tour de France, would all be using waxed chains.

After all, each team has a dedicated fleet of highly experienced professional mechanics available at their beck and call.

In reality, though, the specific challenges of professional cycling and multi-day races such as the Tour make running waxed chains more difficult than many imagine.

It can be done, of course, and some teams have engineered creative solutions to make it possible.

Not everyone is convinced the purported benefits are worth the extra effort, though.

There are also things such as sponsorship arrangements to consider – as we’ve previously pointed out, the pros don’t always get the best of everything. There’s plenty of great tech the pros can’t have, but you can.

To find out why some teams use waxed chains and some don’t, I spoke to performance experts Dr Xavier Disley, of AeroCoach, Dan Bigham, performance engineer at Ineos Grenadiers (and former UCI Hour Record holder), and Jenco Drost, head of performance equipment at Visma-Lease a Bike.

Easier said than done

At its most basic, the process of waxing chains is fairly simple.

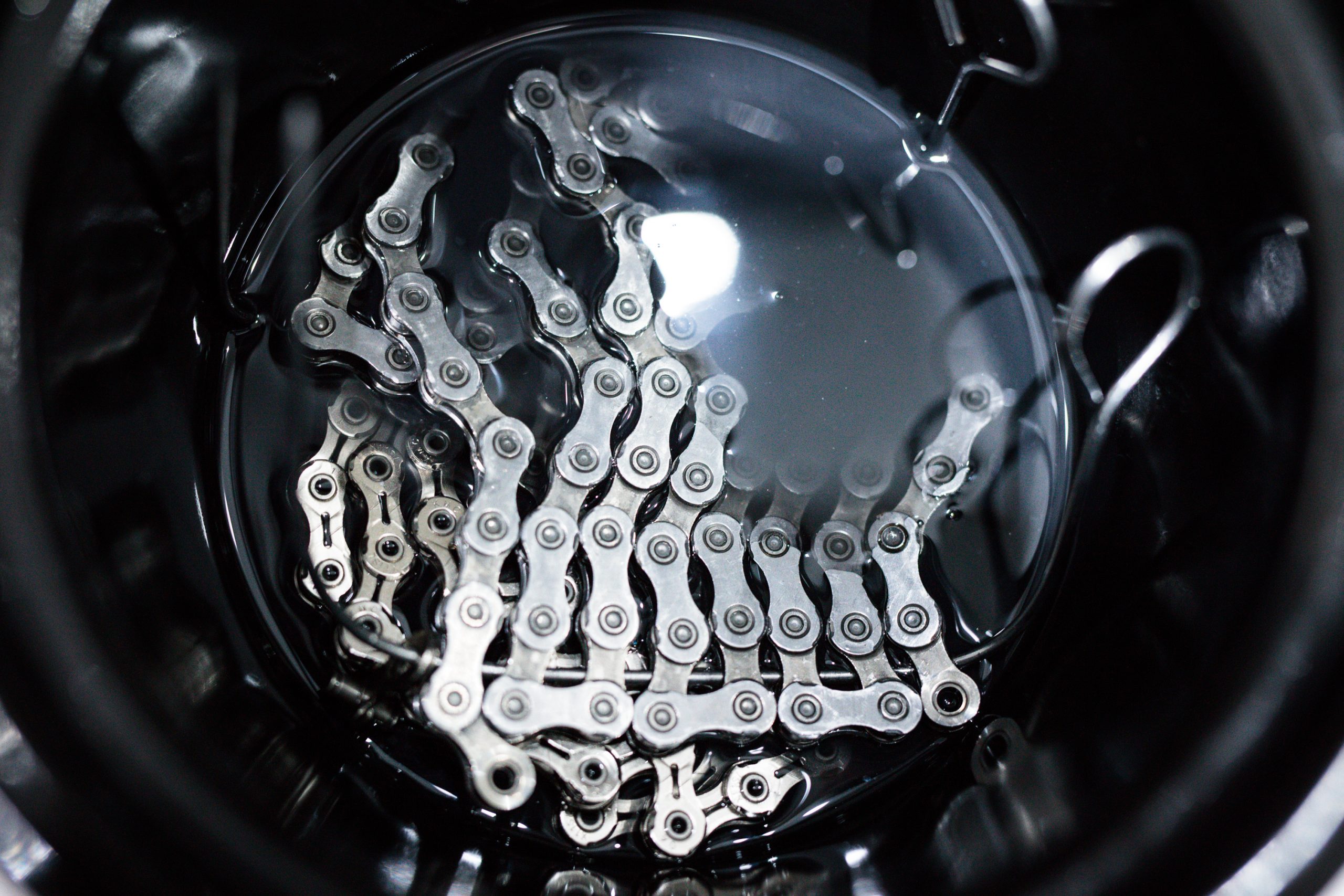

You clean it thoroughly of any dirt or factory grease, immerse it in a heated container of molten wax for a few minutes, then hang it to dry.

Once the wax has solidified, the chain links simply need to be broken so it can be re-installed on a bike.

The issue for professional cycling teams, especially those on the road at events such as the Tour, is doing this at scale.

While the individual steps aren’t beyond the capabilities of seasoned mechanics, the process can be time-consuming, especially when there are dozens of bikes to clean, maintain and restore to pristine condition every evening.

UAE Team Emirates, for example, appears to be ferrying at least five Colnago V4Rs road bikes and two Colnago TT1 time trial bikes around France for its team leader Tadej Pogačar.

Considering a Tour de France squad is made up of eight riders, all requiring multiple road and time trial bikes, and countless spares (to account for mechanical failures, crashes, spec changes and so on), the scale of the job starts to become apparent.

Given this, and the fact that they only have a few hours every evening in which to complete all of their tasks before the race continues the next day, professional mechanics typically use pressure washers and dedicated bike cleaning products to make the cleaning process as efficient as possible.

These things are generally incompatible with waxed chains, though, because a pressure washer would simply blast the wax off, leaving it almost completely unlubricated, while the solvents in bike cleaners can contaminate the wax, causing a significant degradation in performance.

It’s also worth remembering that wax-based and oil-based chain lubricants are incompatible, so teams will generally look to take an all-or-nothing approach, in order to reduce the risk of cross-contamination.

As chain quick-links are near-ubiquitous nowadays, mechanics could remove the chain prior to washing each bike, re-installing it (after re-waxing) or another freshly waxed chain later.

When repeated many times over, though, even quick jobs such as this lengthen the process.

Likewise, Xavier Disley notes freshly waxed chains typically need to be broken in after being installed on a bike (due to the excess wax that settles on a chain during immersive waxing) in order to reach optimum efficiency and shifting performance.

This is typically done by riding the bike for 10 to 15 minutes, which enables any excess wax to be abraded off by the chainrings and cassette.

While that’s not a Herculean challenge for one bike, it all adds up when you have to do it for multiple bikes, every day.

Ultimately, running waxed chains at an event such as the Tour requires a significant investment of extra time and resources – things that are limited when you’re on the road for three weeks, even for the richest teams in the peloton.

To borrow from my A-level economics theory, this means there are potential opportunity costs to running waxed chains, because time spent facilitating it could mean time spent not doing something else.

Is it worth it?

Beyond the extra time and resources running waxed chains demands, there are also questions about whether it’s worth it.

Not everyone is convinced the claimed efficiency gains, compared to top-quality oil-based lubricants, are as great as some claim.

Disley says that according to his own testing, “There is little difference between an exceptionally good lube and a waxed chain – depending on how well you’ve waxed the chain, it could even be worse”.

Dan Bigham, of Ineos Grenadiers, agrees, saying: “Primarily, gains are coming from simply ensuring you have a clean and properly lubricated drivetrain.”

Given team mechanics deep-clean and re-lubricate team bikes every day, a dirty chain isn’t something professional riders at the Tour ever need to worry about.

Bigham also points out that while Ineos Grenadiers may not be running waxed chains, that doesn’t mean the team hasn’t optimised its lubricant selection.

“Nowadays,” he says, “it’s accepted [that] benefits come from thoroughly cleaning and lubricating the drivetrain (typically via ultrasonic immersion).”

“Whether that lubricant is wax or something else is a point for discussion. I am a big fan of waxing, but Muc-Off’s Ludicrous AF [chain lube] does perform very well too.”

Muc-Off (a team sponsor) has also supplied the team with ‘fully prepared chains’ ahead of big races, in order to reduce the workload during the event, and ‘a cleaning and lubrication station’ for re-optimising chains throughout the race, according to Bigham.

Mechanical implications

Beyond potential gains, there are mechanical implications to consider.

Increasing the frequency with which the mechanics swap chains on team bikes also increases the risk of mistakes being made during re-installation (such as an improperly installed quick-link).

Given the professionalism and experience of most WorldTour mechanics, such mistakes would likely be vanishingly rare. However, they’re still human and the potential for errors can’t be eliminated completely.

Because each chain will have a subtly different wear pattern, it’s also possible there could be inconsistencies in shifting between them too.

When a fresh chain is installed, the mechanics will therefore need to check whether the shifting is working perfectly – taking yet more time and resources.

If a shifting issue is missed and a team’s key rider drops their chain or misses a shift at an inopportune moment, we only need to remember ‘Chaingate’ at the 2010 Tour de France to imagine how the potential gains could disintegrate quickly.

How some teams make it work

Despite the logistical hurdles, some teams are convinced the juice is worth the squeeze and have implemented workflows to enable them to run waxed chains at races such as the Tour.

Jenco Drost, head of performance equipment at Visma-Lease a Bike, says he believes the “benefit can be multiple watts compared to normal lubrication”.

He also says “a wax treatment takes more time in preparation, but the complete drivetrain stays cleaner, which saves time afterwards”.

Drost concedes “the logistics are a bit more complicated” but that the team has developed a system of “running multiple chains per bike and big-batch wax treatments”.

Lidl-Trek is also all-in on waxed chains at this year’s Tour, thanks to a partnership with Belgian brand, Cyclowax.

Cyclowax has provided the team with waxed chains and the equipment to re-wax them on the road.

At this year’s Grand Depart, the brand also showed off a prototype automatic chain waxing machine, which enables a chain to be re-waxed without taking it off the bike, in about 30 minutes.

It’s a novel idea – and one that may help teams automate the process in the future.

For now, though, Lidl-Trek has only one such machine and considering how many bikes it needs to get through every evening, it’s not solving the overarching logistical problem.

Instead, the team is relying mainly on traditional methods – heated ultrasonic immersion baths filled with Cyclowax’s proprietary chain wax.

This enables the mechanics to wax multiple chains in a single batch, but the chains must be removed from the bikes first.

Some teams also use wax-based drip lubes.

UAE Team Emirates, for example, uses AbsoluteBlack’s GraphenLube, which is available in hot melt (for immersive waxing) or drip lube form.

As some amateur chain waxers do, the team could start with immersively waxed chains and top them up as necessary with the drip lube.

This is a practical solution to many of the issues cited above because it cuts down on the number of times the chain needs to be removed from the bike for re-waxing.

In my experience though, wax-based drip lubes typically don’t perform as well as immersively waxed chains, either in terms of cleanliness or longevity, which somewhat negates the point of switching from oil-based to wax-based lubes in the first place.

Money makes the world go round

Even if there are ways for teams to make it work, it’s also worth remembering that the Tour de France is a professional sporting event run, not out of benevolent love for cycling and athletic endeavour, but for profit.

The right chain lubricant might help smooth a rider’s shifting and save them a few watts, but sponsorship deals are what keep the show on the road.

For a team sponsored by a chain lube company that doesn’t offer wax-based chain lubes, for example, it’s unlikely the riders will be allowed to use waxed chains or wax-based lubes.

Ineos Grenadiers and EF Education-EasyPost, for example, are both sponsored by Muc-Off – a brand that only makes oil-based chain lubricants.

Regardless of what Dan Bigham or either teams’ riders think about waxed chains, that likely has the biggest influence on which chain lubricants the teams use.

Pro teams sometimes use non sponsor-correct equipment, of course, but doing so risks damaging important commercial relationships.

That could be a worthwhile risk for something as important as a saddle (Mark Cavendish has been racing on a Fizik Arione at this year’s Tour, despite his Astana Qazaqstan team being sponsored by Prologo, for example). However, going off-brand for a chain lube is likely to be seen as an unnecessary risk if the riders and performance staff aren’t convinced the potential gains are worth it.

Of course, we might take Bigham’s claim that Muc-Off’s Ludicrous AF chain lube is comparable to wax in terms of performance with a pinch of salt, given his employers have a prominent commercial relationship with the brand.

However, it’s worth remembering the same scepticism should apply to teams sponsored by brands producing (and marketing) wax-based chain lubes too.

Tadej Pogačar dominating the sport doesn’t prove that AbsoluteBlack’s GraphenLube is “the best lubricant on the market” any more than Team Sky’s dominance of the previous decade proved that Muc-Off was making the best lubes available back then.

Likewise, Cyclowax is an ‘official partner’ of the Lidl-Trek team, for example, which suggests there could be a financial incentive for the team to use and promote its products.

That doesn’t mean the relationship isn’t symbiotic – Lidl-Trek may have been able to partner with a number of lubricant brands, but chose Cyclowax because it truly believes in its products. However, it means we should take Lidl-Trek’s claims about its partner’s products with the same pinch of salt as we would with anything else.

What does this mean for everyday riders?

As always, what’s best for professional cycling teams isn’t necessarily what’s best for everyday riders.

It’s important to remember that when professional teams do something, or use a product or piece of equipment, it’s not always motivated purely by performance – there’s almost always a financial incentive too.

Performance is critical, of course, but it isn’t the only consideration, even for the most well-funded teams.

Even if the claimed performance benefits of waxed chains and wax-based lubricants are overblown, there’s no denying they can help keep your drivetrain exceptionally clean, reducing the wear and tear on parts.

For everyday riders, the money saved by having to replace parts less frequently is likely the biggest draw.

Likewise, the logistics of waxing a few chains here and there are far less of a barrier for riders with only a few bikes to look after than for a pro team restoring dozens of bikes to pristine condition every day within the space of a few hours.

That said, waxed chains won’t be right for everyone.

As always, it’s important to take a level-headed look at the type of riding you do and read independent reviews of products on websites such as BikeRadar (other websites are available) before making a decision on what’s right for you and your bike.